A historian is accusing the Jewish Museum in New York of distorting the truth about a major artist’s ethically contentious conduct during and after World War II.

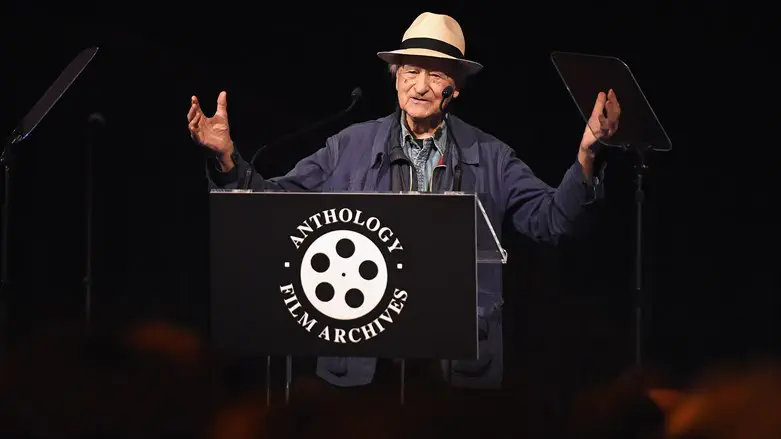

Lithuanian-born Jonas Mekas, the godfather of American avant-garde film, who died in 2019, is the subject of a major exhibit currently running at the museum.

The exhibit, “The Camera Was Always Running,” celebrates Mekas’ role as a “filmmaker, poet, critic, and institution-builder” who “was forced to flee his native Lithuania and [was] unable to return until 1971.” Although Mekas was not Jewish, he ran a series of film screenings at the museum in the late 1960s, when it was one of the few major venues in New York City hosting contemporary art.

According to Michael Casper, a researcher at Yale University who specializes in the history of Lithuania (and Hasidic Brooklyn), Mekas was more involved with the Lithuanian movement that aided the Nazi cause than he had ever let on.

A few years before the exhibit opened, Casper published an essay in the New York Review of Books documenting Mekas’ role in running two newspapers containing Nazi propaganda and antisemitic bile during World War II. Casper also noted that “unlike other members of his activist circle, Mekas was not an anti-Semitic polemicist.”

The historian argued that Mekas, in his extensive repertoire of films and writings, and in interviews, fostered confusion about his wartime experience by conflating dates and fudging certain details while allowing many to believe he was a Jew or a Holocaust survivor, or that he had spent the war fighting against the Nazis.

Casper had hoped an exhibit on Mekas at the Jewish Museum would go beyond celebrating his artistic achievements and interrogate the uncomfortable aspects of Mekas’ past that Casper had surfaced.

“Surely the Jewish Museum would address the essential question of Mekas’ activities during World War II and his life’s intersections with Jewish history in Lithuania, one of the most important centers of modern Jewish culture and one devastated by the Holocaust,” Casper wrote in a review of the exhibit published in Jewish Currents. “If not there, where?”

Instead, what Casper says he encountered at the museum was the same uncritical hero-worship to which Mekas had always been treated.

“The curator introduces dozens of factual errors and misleading interpretations, contributing not only to the revisionism surrounding this single artist, but mobilizing a sentimental attachment to Mekas in a way that erodes the integrity of the broader historical record, and the Jewish history that the museum should be committed to honoring,” Casper wrote.

In a response to a request for comment by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, the museum’s senior director of communications, Anne Scher, released a statement defending the exhibit and referring to Casper’s arguments as “unsubstantiated points.”

She added that the exhibit’s curator, Kelly Taxter, did extensive research on Mekas’ life. Taxter’s work benefited from access to Mekas soon before he died and to his archive. She has worked closely with his estate, which was involved in the exhibit and in the museum’s effort to defend it.

“No evidence has been found to support Casper’s claim that Mekas falsely presented his early biography for personal benefit,” Scher wrote. ”The Jewish Museum stands behind the artist’s telling of his own life story in presenting an exhibition of his cinematic work.”

Taxter, meanwhile, said she had touched upon Mekas’ wartime experience in an essay accompanying the exhibit and that it was “sketched” in the museum’s displays. But she added that this topic was not “the thrust” of her curatorial work.

“The exhibition was not about Jewish history or the history of Jews in Lithuania; it is an exhibition about a filmmaker whose consequential past intersected with a similarly consequential era in the history of the Jewish Museum and whose artwork, I posit, is largely informed by his experiences of flight, exile, and living as a refugee,” she said in a written comment.

It was not the first time the museum had contemplated how it would respond to the questions arising from Casper’s findings. Before the exhibit opened, the museum distributed an internal memo titled, “Talking Points for Frontline Staff,” a copy of which was obtained by JTA.

The two-page memo names Casper and attempts to refute his essay by distilling concerns into a set of questions: Was Mekas an antisemite or complicit in Nazi atrocities in Lithuania? Why was the museum doing an exhibit on him? Staff were then supplied with reassuring responses, called “key messages.”

“The Jewish Museum would never present the work of an artist who was complicit in Nazi atrocities,” reads one of the key messages. It is followed by a “background,” which argues that what Casper sees as Mekas’ “intentional misrepresentation of historical events” is simply Mekas’ “manner of coping with trauma.”

The memo also notes the official reason for the exhibit, which is to revisit Mekas’ connection to the museum — which had been forgotten until he mentioned it to one of the museum’s curators in passing.

A second memo distributed to staff, also obtained by JTA, anticipated further questions about why the museum was the proper place for an exhibit on Mekas, who wasn’t Jewish and whose work didn’t focus on Jewish content.

“Why here?” the memo asks. “Jonas Mekas’s life and work reflect stories and experiences shared by refugees and immigrants of Jewish heritage in the wake of World War II.”

For Casper, this language reflects the museum’s larger failure to rectify the confusion about Mekas and to clarify that while Mekas may have been a refugee, the circumstances of his exile from Europe were vastly different than those of a Holocaust survivor.

In 1941, Casper has pointed out, Mekas was writing poetry and living the life of a budding intellectual in or near Birzai when the town’s 2,400 Jews were massacred in a forest by Nazis and their Lithuanian collaborators.

While some people have assumed that when Mekas talked about fleeing Lithuania he was talking about fleeing the Nazis, the truth is likely quite different, according to Casper. Mekas had stayed in the country throughout the war right until the Soviet Union was on the cusp of pushing the Nazis out. When he fled, he only traveled deeper into the Third Reich, boarding a train to Vienna.

Before he could reach his destination, however, Mekas’ train was redirected and he was detained by Nazi officers for an unknown reason and eventually forced to work in a German factory for a few months. The incident, which Mekas never fully explained, looms large in the image he and his supporters have projected, crowding out, according to Casper, the memory of his earlier wartime experience.

The exhibit has garnered positive reviews, primarily in the art press but also in the New York Times. The Times review refers to Casper’s revelations but uses them to assert that in Mekas’ case, concepts like reliability and consistency cannot serve as proper barometers for truth-telling. “It’s Mekas’s refusal to impose any single narrative on his work that gives it its truth,” The Times wrote.

These positive reviews, however, belie other, decidedly different reactions to the Casper affair. At least some of the museum’s staff are angry that the exhibit didn’t tackle Mekas’ World War II record, according to interviews. And while the staff members are not willing to go on the record with their criticism citing a prohibition on speaking to the media, several cultural critics and scholars reached by JTA are.

Richard Brody, a film critic of The New Yorker, who is Jewish, told JTA in an email that he found the allegations in Casper’s original essay “cogent and troubling.” He said he hadn’t gone to see the Mekas exhibit but that he’d “expect any exhibit centered on him to address Casper’s findings seriously.”

Also Jewish, film critic J. Hoberman, a lifelong Mekas admirer, had called Casper’s article a “bombshell” and said it “stirred up conflicted feelings.” He told JTA in an email that he has “great respect” for Casper’s scholarship and expressed misgivings about the exhibit.

“Mekas is an undeniably major figure in American culture,” Hoberman wrote. “Nevertheless, I would have preferred a less simplistic exhibition or better that the Jewish Museum had honored any one of a dozen Jewish filmmakers (many of them women) active in avant-garde cinema.”

Meanwhile, Jeffrey Shandler has been following events from an academic vantage point. A professor of Jewish studies at Rutgers University, Shandler studies Jewish memory practices around the Holocaust, including the role museums play in commemorating Holocaust history.

Shandler told JTA that he was disappointed with how the museum handled the topic, and that he couldn’t think of a similar example in the long history of controversial curatorial decisions by Jewish museums.

“They are taking at face value the narrative that Mekas had crafted about his wartime experience,” he said. “It would be problematic anywhere, in any museum. But I think it is doubly so in a Jewish museum. It really raises questions about their understanding of their mission.”

Several people have pointed out with concern that the exhibit is funded in part by the Lithuanian Council for Culture, the Lithuanian Culture Institute and the Lithuanian Film Centre, which are government entities. Lithuania has a complicated relationship with its Holocaust past, rejecting the kind of revisionism that has taken root in neighboring Poland but also struggling with the role that local collaboration played in the murder of 95% of the country’s prewar Jewish population.

Scher, the museum spokesperson, said the museum makes its curatorial decisions independently from the interests of funders.

Years before the exhibit, a 94-year-old Mekas allowed himself to be interviewed by Casper but rejected the conclusions of the scholar’s inquiries. When Casper published his original essay, the artist dismissed it as “fake news.” The incident prompted Mekas to claim the final word by submitting to an interview with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, the recording of which is more than six hours long.

While some of Mekas’ friends and disciples expressed shock and dismay about Casper’s revelations, many people came to Mekas’ support, criticizing or even attacking Casper. “The wagons started circling immediately to protect a sacred figure of the avant-garde,” wrote Film Quarterly editor B. Ruby Rich.

In defending Mekas, Taxter, the exhibit’s curator, has gone farther than most.

Responding to a request for comment from JTA, Taxter sent a copy of Casper’s Jewish Currents essay annotated with dozens of comments, offering an almost point-by-point rebuttal.

She disputed various facts and characterizations, writing that “Casper insinuates in this article and in his NYRB article that Mekas was a Nazi sympathizer or had Nazi allegiances, but he has yet to present any evidence to support the claim. In the absence of such substantiation, available historical material and Mekas’s biography have been accepted as fact.”

She also claimed that Casper became so zealous about this work that he harassed Mekas or worse.

“In ongoing correspondence between Michael Casper and Jonas Mekas, Casper regularly demanded information from Mekas under the guise of so-called testimony,” she wrote. “The tone of these emails is often aggressive, with the cumulative effect of these emails being that Casper was bullying or even threatening Mekas.”

To back up this allegation, Taxter quoted from Casper’s emails to Mekas and eventually supplied 40 pages of email exchanges obtained through Mekas’ son Sebastian.

In an example of the alleged harassment highlighted by Taxter, Casper had written to Mekas, “You have spent many years erasing important details from your story. What I want is for you to confront and acknowledge them, as painful or difficult as they may be.”

Casper rejected the notion that he harassed Mekas. “The sense of urgency behind my questioning only comes from it being at the tail end of our correspondence, and in response to Mekas’s own style at that time,” Casper told JTA.

Jackie Hajdenberg contributed to this story.