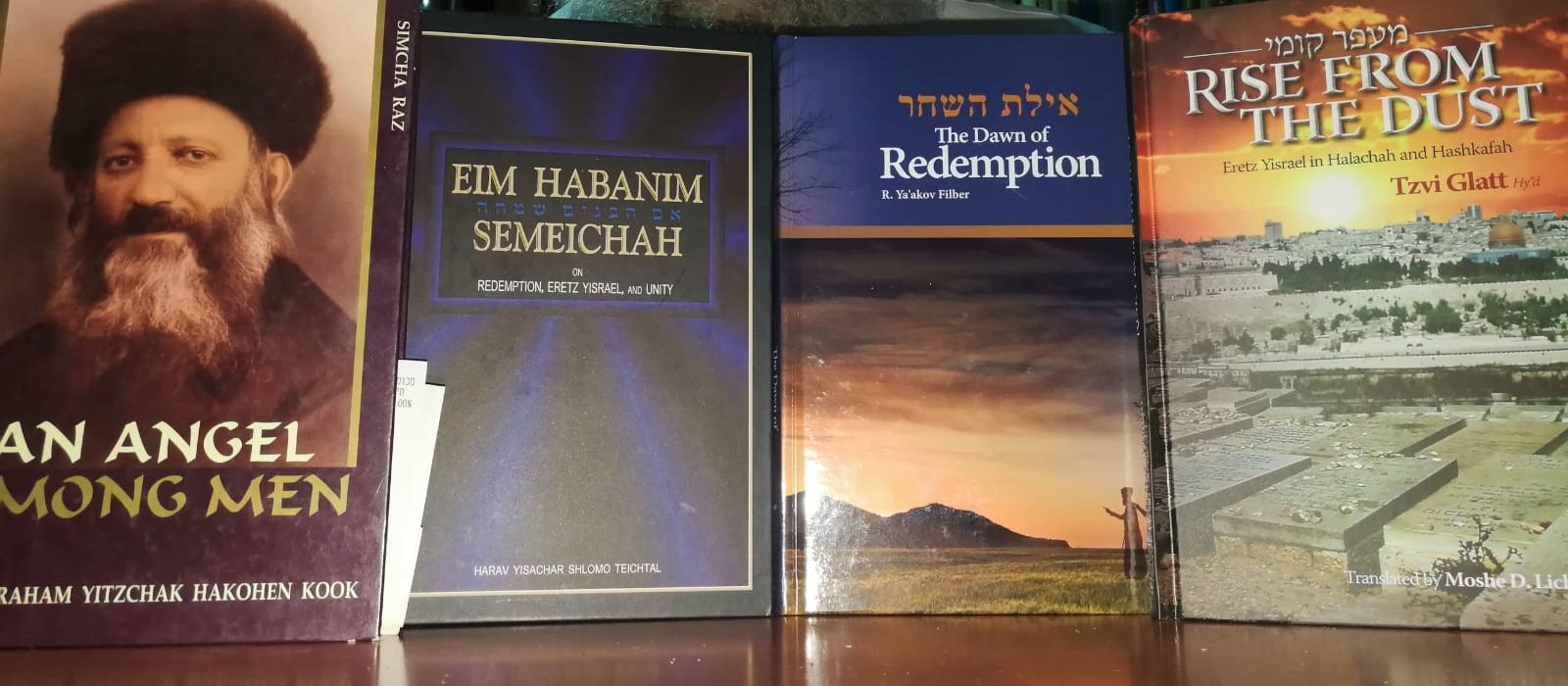

In addition to his own Torah commentaries, Rabbi Lichtman is known for his translations of “Eim HaBanim Semeichah,” “Rise from the Dust,” “Dawn of Redemption,” and “An Angel Among Men,” available at his website: https://toratzion.com/

Our Sages of blessed memory refer to the “Book of Vayikra” as Torat Kohanim (“The Law of the Priests”), for it deals mainly with the laws of sacrifices which are performed by the Kohanim. As such, it is obvious that Eretz Yisrael plays a major role throughout the book since most of its laws depend on the Land, the only place where sacrifices became permissible once the Children of Israel entered the Land.

The very first word of the Torah portion “Vayikra” actually relates to the entire Book of Vayikra. The Torah introduces the book with the words: “He [G-d] called to Moshe, and the Lord spoke to him from the Tent of Meeting, saying….”

As is well known, the letter alef (א) at the end of the word ויקרא is written smaller than the rest of the word. Many explanations have been given for this phenomenon. Most commentators see it as an expression of Moshe’s humility. Although he reached the highest levels of sanctity and closeness to God, he wanted to downplay his role and exalted elevation (see Ba’al HaTurim).

The Zohar, however, offers a completely different answer, one that puts the entire Book of Vayikra in perspective. He sees the small alef as a sign of imperfection. Why is there a small alef? Because this “calling” was imperfect. Why so? For it took place in the Mishkan (Tabernacle) and in a foreign land. For [true] perfection can only be found in the Land of Israel. (Tosafot HaZohar 1, quoted in “Itturei Torah” vol. 3, p.7).

Let us contemplate this answer. There was probably never a period in history during which the Jewish people enjoyed a more intimate relationship with Hashem than the forty-year journey through the desert. Heavenly clouds surrounded them on all sides, protecting them from the elements. Their clothes grew with them and never wore out. Celestial food was delivered to them fresh every day (at no cost). They were led by the greatest prophet ever to live, and he was readily available to answer questions and give advice on religious matters. And perhaps most importantly, they had a portable Beit HaMikdash which accompanied them throughout their journey. There, they were able to offer sacrifices to God and draw spiritual inspiration whenever they needed. Can there possibly be a more ideal situation than this?

When the Jews eventually entered the Land, they had to lead “normal” lives. They had to till the earth to derive sustenance; they had to wage wars to conquer the Land; they had to make their own clothing, and repair or replace them when they wore out; etc. Nevertheless, the Zohar teaches us that no matter how good life is in Chutz LaAretz – even from a spiritual standpoint – something is lacking, for true perfection can only be attained in God’s special Land!

Nowadays, many Jews feel quite satisfied with their spiritual lives outside the Land of Israel. Baruch Hashem, Diaspora communities can boast many fine yeshivot, elaborate schedules of shiurim, glorious chesed organizations, stores and restaurants which adhere to the strictest standards of kashrut, etc. Let us not forget, however, that the Jews in the desert had it even better, yet their existence was considered imperfect, simply because it was in the wrong environment.

Let the little alef at the beginning of this week’s parashah serve as a subtle reminder that we have yet to reach our ultimate goal – to serve Hashem in utter perfection in His Chosen Land.

CLAL YISRAEL

One of the sin offerings (חטאת) described in this week’s parashah is the communal offering the פר העלם which is brought when the majority of Israel commits a sin which incurs the penalty of ka’ret (excision), following an erroneous ruling of the Sanhedrin – Jewry’s highest court.

For example, let’s say that the Sanhedrin rules that a certain form of idolatry is permissible, or that a certain type of work is permitted on the Sabbath. Trusting their judges, most of the Jewish people (or of a single tribe) go out and serve the idol or perform the forbidden act on Shabbat. Then, the judges of the Sanhedrin realize that they issued a mistaken ruling. In such a case, instead of each individual bringing a separate sin offering, the Sanhedrin must bring one par (a young bull) to atone for the sin that it inadvertently caused.

In the Torah’s words: “If the entire assembly of Israel [i.e. the Sanhedrin] shall err, and something is hidden from the eyes of the congregation (קהל); and they transgress one of all the commandments of the Lord that may not be done, and they incur guilt. When the sin that they committed becomes known, the congregation shall offer a young bull as a sin offering and bring it before the Tent of Meeting. The elders of the assembly shall lay their hands on the bull’s head…” (4:13-15).

How exactly do we figure out whether or not a majority of the nation (or a tribe) sinned? Who is considered part of the קהל? The Talmud’s answer is quite shocking: R. Assi said: “Regarding [an erroneous] ruling, we follow the majority of the residents of Eretz Yisrael.”

Accordingly, it is written, “At that time King Shlomo celebrated the [Sukkot] festival – and all of Israel was with him, a great congregation (קהל), from the approach of Chamat until the stream of Egypt – before the Lord our God, for seven days and seven days, [all together] fourteen days (I Melachim 8:65). Let us see. It says, “And all of Israel was with him, a great congregation (קהל).”

Why, then, must it say, “From the approach of Chamat until the stream of Egypt?” From here we derive that these [i.e., the ones who live within the borders of Eretz Yisrael] are called “congregation” (קהל), but those [who live outside the Land] are not called “congregation” (Horayot 3a).

A concrete example may simplify the matter. Let us say that six million Jews live in the Holy Land and seven million live on foreign soil (like today). If three million and ten of Eretz Yisrael’s Jews transgress a sin that the Sanhedrin mistakenly permitted, while only two million Diaspora Jews do so, we consider it as if the majority of the congregation sinned, requiring them to bring only one bullock. Even though a minority of world Jewry committed the sin (five million out of thirteen million), a majority of Eretz Yisrael’s Jews sinned (three million and ten out of six million), and they are the only ones truly considered Kahal Yisrael. “Those [who dwell] outside the Land are not counted” (Rashi, ibid.).

The Rambam applies this concept to another area of halakhah: “We have already explained at the beginning of [Tractate] Sanhedrin that only a beit din ordained in Eretz Yisrael can be called a true beit din, whether [its members] were ordained by someone who received official ordination (semichah), or whether the people of Eretz Yisrael agreed to appoint him as the head of the yeshiva. For the people of Eretz Yisrael are called kahal (congregation), and the Holy One Blessed be He called them ‘the entire congregation,’ even if there are [only] ten men. And we do not pay attention to anyone else in Chutz LaAretz” (Commentary to the Mishnah, Bechorot 29).

HaRav Herschel Schachter, shlita, explains this as follows. Diaspora Jews certainly have Kedushat Yisrael (the special sanctity of being a Jew), and they are even considered part of Klal Yisrael, but only to a certain degree. Jews who live in the Chosen Land, however, have the full status of Klal Yisrael, for the Jewish people are interconnected primarily in and through Eretz Yisrael, nowhere else. (Heard in a public lecture.)

Rabbi Yechiel Michel Tikochinsky (former Head of the Etz Chaim Yeshiva in Jerusalem and author of the book “Gesher HaChaim” on the rules of mourning) sums it up best: “The main strength of Am Yisrael… is in the Land of Israel, and every observant Jew [who moves there] adds strength to the congregation. So now that the gates of the Land are opened before us, thank God, every religious Jew and every rabbi should remember this and apply the lesson to themselves” (Sefer Eretz Yisrael, chap. 25).