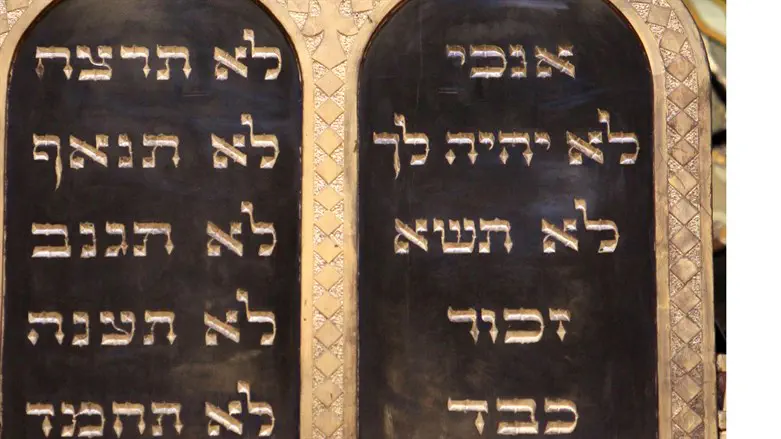

One of the reasons for fasting today, on the 17th of Tammuz, Shiva Asar b'Tamuz, beyond the breaching of the walls of Jerusalem, is that on this day "the first set of tablets were broken"; Moses descends from Mount Sinai, sees the golden calf and breaks the Tablets of the Covenant. Despite the tragic event, there is a Midrash that states that in retrospect, this was an advantage:

"The Holy One blessed be He said to him: ‘Do not regret the first tablets, as they were only the Ten Commandments. But on the second tablets that I am giving you there will be [halakhot], midrash, and aggadot" (Exodus Rabbah 46:1).

In other words, it was precisely the breaking of the first tablets that allowed the forces of the Oral Torah to be manifest. A great disaster that extinguishes the sun makes it possible to see the light of the stars.

In meetings with groups around the country, I ask people to try to define for themselves benefits that have grown in their lives in the last ten months since the outbreak of the war. The answers amaze me time and time again: from those whose economic or social situation was positively affected by the war; to the previously unimagined resilience that families and couples found within themselves; through the people for whom long reserve service defined for them and their families a connection to something great and meaningful.

We are not asking for the tablets to be broken; we are fasting on Shiva Asar b'Tamuz to atone for this. But in retrospect, out of the pain, the second set of tablets can emerge.

The bad will pass

The good will prevail

With God's help.

Have a meaningful fast!

And while thinking about how these past months have affected us, it is only natural to try to see who is responsible. It is clear that decision makers bear personal responsibility, but we must not forget that, first of all, most decisions are made due to the public mindset and not just the whims of leaders (if Netanyahu, for example, had decided to attack Gaza on October 6th, would the public have supported him?); and secondly, criticism of the leadership is supposed to be without attribution of malicious intent.

No one meant harm here for the simple reason that decision makers are part of us. I had the chance to hear a girl from one of the kibbutzim of the Gaza envelope who claimed that "we were deliberately abandoned" and that "the leadership should be worthy of this people"; only later it turned out, embarrassingly, that the girl's father was a senior commander in the area; so, who exactly "abandoned" her?

The automatic narrative that "the leadership is to blame" – which has become the dominant narrative ever since the Yom Kippur War – is a postmodern worldview that attributes ill intent to all authority (and, of course, ingratiates itself with the majority of the public, which by nature is not authoritative).

Moreover, this is a perception that fosters the personal rather than the collective position; ie, that we are in the "customer" vis-à-vis the country which is supposed to please us. The Torah view is that we are not customers but partners in the state. By the way, this is the right way to criticize any economic, educational or family system. We will impartially criticize the failures of the commanding, managerial and governmental echelons, but with the recognition that we are all interested in the same thing – the good of the people of Israel; we may then find that such criticism will also be more effective.