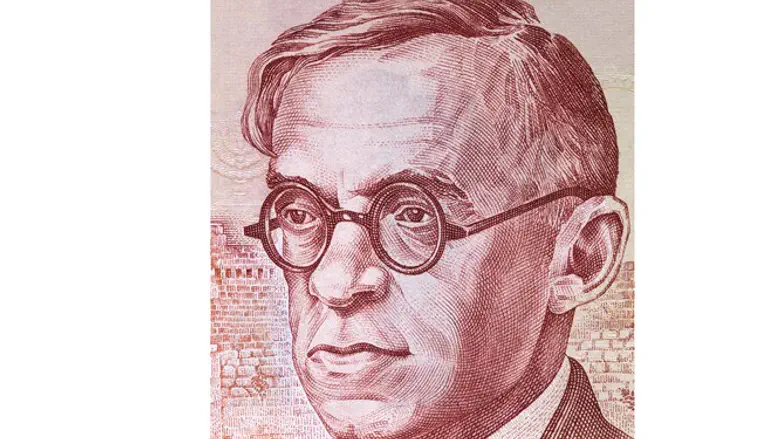

In the midst of the Three Weeks of mourning for tragedies that have befallen the Jewish people throughout our history, it is worthwhile to take note of the legacy of Ze’ev Jabotinsky, whose yahrzeit falls on the 29th of Tammuz. One of the best ways to pay tribute to the memory of this man of ideas and action is to put into practice a central lesson of his extraordinary life by calling for victory in Israel’s just and moral struggle against its enemies.

Jabotinsky stands at the forefront of Israel’s founding fathers. Statesman, writer, orator, soldier and leader - these are but a few of the words describing the multifaceted man who abandoned a promising career as a rising star in the Russian literary world in the early 1900s to embark on the difficult path of serving the Jewish people’s cause for national liberation, the cause of Zionism.

Often described as the founder of Zionism’s “right-wing,” Jabotinsky was a controversial personality during his lifetime, in large part due to his insistence on the now widely-accepted notion that Jews have the right and obligation to defend themselves. The study of his life and thought has been the subject of increased attention in recent years, which seems to be indicative of a thirst for something that is lacking in the current Jewish political and cultural milieu.

He inherently knew that while Jews have HaTikvah, Arabs have their own “hope” as well, one which is focused on the destruction of the Jewish State, whatever its size. Other leaders in the Zionist movement called for restraint in response to vicious Arab attacks on Jewish civilians in the Land of Israel in the decades leading up to the establishment of the state. They preached patience in the face of the British betrayals that pushed its founding further and further off even as the storm clouds of the Shoah began to form in Europe.

Other leaders in the Zionist movement called for restraint in response to vicious Arab attacks on Jewish civilians in the Land of Israel in the decades leading up to the establishment of the state. They preached patience in the face of the British betrayals that pushed its founding further and further off even as the storm clouds of the Shoah began to form in Europe.

In contrast, Jabotinsky boldly and unabashedly called for Jewish self-defense, evacuation of the Jews of Europe for resettlement in their ancient homeland, and the establishment of Jewish sovereignty on both sides of the Jordan River. In other words, he called for victory.

Despite being smeared as an extremist and mocked as an unrealistic dreamer, Jabotinsky was undeterred. He inherently knew that while Jews have HaTikvah, Arabs have their own “hope” as well, one which is focused on the destruction of the Jewish State, whatever its size.

In 1923 he introduced a concept known as “The Iron Wall,” which demonstrated an understanding that the main obstacle to peace was the blanket Arab refusal to accept the right of Jews to establish a Jewish State in the Land of Israel. He keenly observed that peace would not be possible so long as the Arabs believe that they have a chance to put an end to that state and establish an Arab one in its place.

Contrast this with the constant refrain we hear from the false peace-peddlers of our time who call for endless compromises with an enemy that has not forsaken its dream of destroying Israel. “You don’t make peace with your friends, you make peace with your enemies,” they tell us. To this misplaced slogan, we should respond with what thousands of years of human history have demonstrated, “You don’t make peace with your enemies, you make peace with your former enemies.” To cite an obvious example, peace with Germany and Japan would not have been possible at the conclusion of World War II had those two nations not given up on the idea that they could defeat the Allies.

If “The Iron Wall” emphasized the practical aspect of Jabotinsky’s approach to pursuing victory, something akin to “peace through strength,” it was also a function of the sense of dignity and the unique spirit of majesty at the heart of his worldview, which he termed Hadar in Hebrew.

Thus, the sons and daughters of ancient kings of Israel were not to rely on broken promises from colonial powers to achieve their rights like beggars in the shtetls of Eastern Europe or dhimmis in the mellahs of North Africa. If necessary, they had to be prepared to fight to defend themselves and realize their rights as their forebears had millennia ago. This was not only a matter of realpolitik, but a question of self-respect.

It was therefore no accident that it was the students of Jabotinsky who against all odds and with tremendous self-sacrifice put an end to a British colonial rule that had essentially closed the doors on Jewish immigration while millions were being slaughtered in the Holocaust.

One would therefore think that the concept of striving for Israeli victory would have taken root in the newly-formed state. But in Israel’s formative years, it was Jabotinsky’s opponents who held political sway and set the tone for the subsequent approach of military success without the larger goal of decisive victory. The Likud Party’s electoral dominance, which began in 1977 and continues to the present, has for various reasons failed to result in a course-correction in this regard.

Absent a clear objective of victory, while Israel has consistently defeated its Arab adversaries on the battlefield over the course of seven decades, it has often empowered the illegitimate “hope” of its enemies by giving credence to their false narrative, exercising excessive restraint, refraining from working towards their complete defeat or even rewarding them with outright concessions. This cycle of negative reinforcement has in one form or another repeated itself in seemingly endless fashion down to the present time, to which recent events in Gaza attest.

Some twenty-five years after the Oslo Accords, more and more Israelis and their friends around the world have come to recognize the foolishness of the “land for peace” scheme, and the folly of continuing to enable an Arab rejection of the Jewish State that underlies the conflict. There are signs that a new approach is emerging, one that places the concept of Israeli victory at the center of a new paradigm.

Recently, that new paradigm received a boost when an event titled “Oslo Failed, Victory Now” was held on July 4th at the Menachem Begin Heritage Center in Jerusalem. Given Begin’s status as Jabotinsky’s student, the setting was of particular significance.

The gathering brought together panelists that included current and former members of Knesset, security officials, and specialists on the Middle East, and was held under the auspices of the Israel Victory Project (IVP). The IVP is an initiative of the Middle East Forum, a think tank headed by Daniel Pipes.

Since launching in 2017, the initiative has led to the creation of Israel Victory Caucuses in both the United States Congress and the Israeli Knesset to call for a decisive Israeli victory. Over the last year, from the halls of Congress to the corridors of the Knesset, supporters of the project have begun to outline a fresh approach to the Arab-Israeli conflict, one that proposes to stop rewarding Palestinian rejectionism.

The IVP has tapped into a rising sentiment that the time has come for a change in direction after the failure of Oslo and numerous disastrous attempts to force its discredited approach over the last decades. The two caucuses have united Israeli politicians and their pro-Israel counterparts in America and have rapidly expanded their combined ranks, which now number close to 60 lawmakers from multiple political parties.

This development is hopefully but one manifestation of a broader realization that the time has come for Jews worldwide to build new momentum in our pro-Israel advocacy in light of recent developments in the U.S. and on the international scene. Like Israel, we cannot merely sit back and allow events to overtake us. We have to regain the initiative. We too must strive for victory.

On this anniversary of that summer day in 1940 when Jabotinsky was suddenly taken from the Jewish people as he attempted to raise a Jewish army to fight in World War II, let us therefore not only remember the man. Let us remember his Hadar. Let us endeavor to rediscover a sense of Jewish majesty and the belief, confidence and will to strive for victory.