There are two schools of thought on the Holocaust and art, on their compatibility.

The members of one school cannot be comfortable with the idea that such ultimate horror could be reflected by artistic means.

And there is another school of thought, one that sees the means of creative deeds as an opportunity to express, to convey, and to connect. To express at least some of the ocean of emotions and thoughts evoked by such bottomless tragedy; to convey a multitude of messages, from hope against hope to the last subtle goodbye; to connect between those who were taken from life brutally and abruptly, and those who survived; and also, importantly, to connect between the generations

The Arrivals, Departures exhibition (on display June – November 1, 2018) at the Hecht Museum at the University of Haifa is a gem from several points of view: it is a fine presentation of not so widely known or exhibited Jewish artists from the Ecole des Paris, the School of Paris; it is a meticulously researched historical observation of the tragic period that defined their lives; and it is a soulful journey returning those eighteen tattooed souls back to us, their brethren, and to the wider public. To the world.

Art historian and curator Dr Rachel Perry, graduate of both Columbia and Harvard, with many years of experience working in Paris, sees the second school of thought as a challenge. She took her international students on a remarkable journey

The exhibition is also a glimpse of the collection donated by Dr Oscar Ghez to the Haifa University and the state of Israel 40 years ago. So far, only seven of 137 art works from that great donation have been permanently displayed at the Hecht Museum.

The main team who conceived and produced the exhibition, Dr Rachel Perry and her students from The Weiss-Livnat International MA Program in Holocaust Studies at the University of Haifa worked in close co-operation with the Ghetto House Fighters Museum and Yad Vashem, both of which loaned art works from their collections to the exhibition. The Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, Poland and Memorial de la Shoah in Paris provided valuable documentation and records.

On personal level, the role of two people in particular was crucial: Dr Oscar Ghez's son, Dr Claude Ghez provided the ten great art works from his family’s collection at The Petit PalaceModern ArtMuseum in Geneva, established by his father, to be shown in Israel for the first time and Nadine Nieszawer, well-known expert on the Ecole des Paris, the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, who put her top-level knowledge of art and her heart into the project.

Voiceless Screams: Holocaust & Art

The exhibition shows some works created by the artists while they were in detention. To me, it is filled with powerful, soundless screams. The works shown at this exhibition were saved miraculously and heroically by an inmate, the artist himself , Isis Kischka who donated these priceless works to Ghetto Fighters House Museum in Israel.

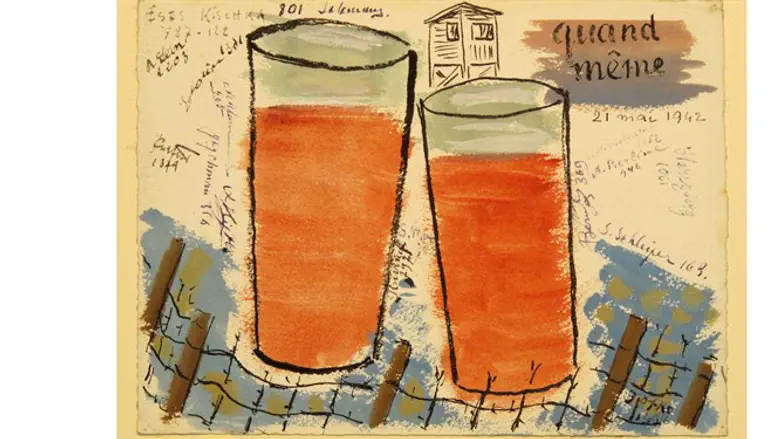

If I were making the poster for this exhibition, I would use the small watercolour by Jacques Gotko which, in fact, was the invitation to the exhibition in the Compiegne camp organised by the imprisoned artists for their brothers in tragedy.

The work is signed “Gotko, 1496”, with the numbers being the artist’s number in the camp. On the invitation, there are two glasses touching each other in a toast, and a sign above them: Quand méme [Despite Everything!..] A piece of barbed wire is arranged around the glasses. But the colour of the liquid inside the glasses rounded by barbed wire is bright orange. As bright as the sun.

Later on, I saw the first draft for the exhibition's poster: it was, in fact, the Quand Meme.

Ecole des Vitebsk: The Paradox of the Ecole des Paris

Paradoxically enough, the very formation of the Ecole des Paris as a group came from outside, and was denounced by the hostile and xenophobic French critics and journalists in 1930s who were quite irritated by the talent of those poor emigrants, many of them Jewish, whom the French snobs tried to discredit and alienate.

From 1935 onward, the hostility towards the Jewish masters in France rose progressively and rapidly, and turned into full neglect and ostracism, on purely racist and anti-Semitic ground, five years before Hitler marched through the Champs Elysée. No mainstream French media published a word about Chagall or other Jewish artists five years before France gave in to the Nazi regime.

Because of the way in which they created their works, because of the character of their outburst of inner freedom, the way of creating an entirely new world by their art, the group of brilliant talents from the wider circle of the Ecole des Paris, definitely those of the Jewish origin, should be called the Ecole des Vitebsk, regardless of the actual place of their birth.

Homecoming

How lucky we are now, able to indulge ourselves with the 85 art works at the Arrivals, Departures exhibition of the artists who are not exhibited as regularly, as Chagall or Modigliani, but who were their colleagues and friends. Among 18 artists exhibited at the Hecht Museum, seven are well-known: Naum Aronson, Max Jacob, Adolphe Feder, Moise Kogan, Roman Kramsztyk, Henri Epstein and Léon Weissberg. Another four are well-known to the connoiseurs, but not so much to the wide public: Joseph Hecht, George Kars, Nathan Grunsweigh and Natalie Kraemer; seven are known to the experts: George Ascher, Abraham Berline, Jacques Cytrynovitch, Alexander Fasini, Jacque Gotko, Karl Haber and Joachim Weingart.

We are stunned by a trove of treasures representing the strong, matured, emphatic art of Natalie Kraemer, the only woman among the artists presented at the exhibition. Among the significant new materials discovered by Dr Perry and her students were the details of the life and the death of Kraemer, about whom virtually nothing was known

Dr Rachel Perry and Dr Claude Ghez with art works by Nathalie Kraemer at the Petit Palais Modern Art Museum in Geneva. (R. Perry)

Dr Rachel Perry and Dr Claude Ghez with art works by Nathalie Kraemer at the Petit Palais Modern Art Museum in Geneva. (R. Perry) Hecht Museum Holocaust artists - works by Natalie Kraemer, displayed in Israel for the first time

Hecht Museum Holocaust artists - works by Natalie Kraemer, displayed in Israel for the first time צילום:

We are delighted by incredibly serene and gentle work by Max Jacob, Viw of Pont-Aven. We are affected by the haunting works by Joachim Weingart and by Léon Weissberg. And when seeing such detail are the medium of a certain work, like a small piece of a fibre cement, 19 x 26 cm, on which the Weissberg's House in the Sun is done, we know that we are going to remember that detail for good.

You go on to the big cache of masterly works of a very able artist, George Kars, with a fantastic Dancer relief on bronze of a petite 12x11 cm size. You will always remember the unutterably sad Self-Portrait of Natan Grunsweig, with the artist wearing kippah and Star of David. And you are happy to uncover a great artist, as Alexandre Fasini was, so many years after the tragic, premature and cruel end of his life.

And the number of the artists is not a coincidence: Rachel Perry told me that she chose the number 18, for Chai, on purpose.

Historical perspective was essential in this art exhibition. Among the 18 artists, there are the only two who survived the war, Nathan Grunsweigh and Joseph Hecht. One more, George Kars, surviving the Holocaust, committed suicide in February 1945. In all, 84% of the artists presented at the Arrivals, Departures exhibition were direct victims of the Shoah.

Adophe Feder. Mother and Child. Oil on canvas. 81 x 59 cm . (C) The Ghez Collection.

Adophe Feder. Mother and Child. Oil on canvas. 81 x 59 cm . (C) The Ghez Collection. :

In his heart-breaking lament put in the form of a Yiddish poem To Our Martyred Artists in 1951, Chagall who returned to his beloved France without his beloved Bella who died in a New York hospital in 1944, , said aloud that many people from the cultural circles were and still are thinking:

"[...] Israel’s brothers, Pissaro’s and

Modigliani’s..., our brothers... led along by

ropes by the sons of Durer, Cranach

and Holbein...being led to death in the crematoriums [...].

( translated from Yiddish to English by Eugene Borowitz , (C) 1993, ARS, N.Y/ADAGP, Paris).

For some reason, this great poem was not translated from Yiddish for over 40 years. Its original is on display at the Israel Museum.

But the most important dimension for me in this exhibition which is its human dimension.

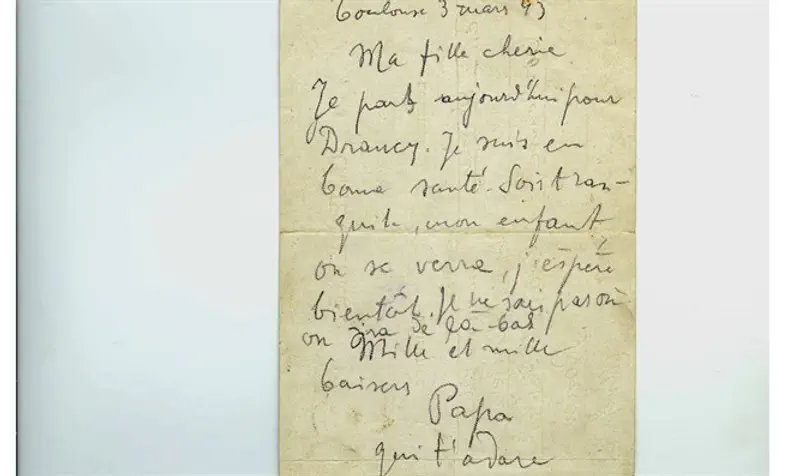

One of the most special exhibits is the carte-postale sent by Léon Weissberg, four days after his arrest by the French policemen who knew him personally and were friendly to him before that, and two weeks before the Nazi train moved him to Majdane. He wrote to his daughter Lydie who did survive and who lives in Paris today. We see the post-card written by the hand of the artist who was talking to his little daughter, we read his heart-wrenching words “I leave for unknown destination…”, and we feel the presence of the person who was annihilated immediately after arriving to Majdanek on March 11, 1943.

This is the Human Dimension in our re-addressing the Shoah today. And this is what motivates us in this ongoing quest: to feel the breath of the people who were torn from life decades ago. Our people.

Now, 77 years and three generations after their deaths, this exhibition has become the Homecoming of those 18 tattooed, tortured souls, thanks to one woman who inspired the team of her students to work on the project with their souls.