The Dutch elections in November sent shockwaves through Europe, as voters delivered victory to Geert Wilders, a hard-right populist known for crusading against Islam, immigrants and the European Union — along with professing support for Israel.

But for some Dutch Jews, who have watched an atmosphere of fear and antisemitism grow since the Israel-Hamas war began on Oct. 7, the results were less surprising.

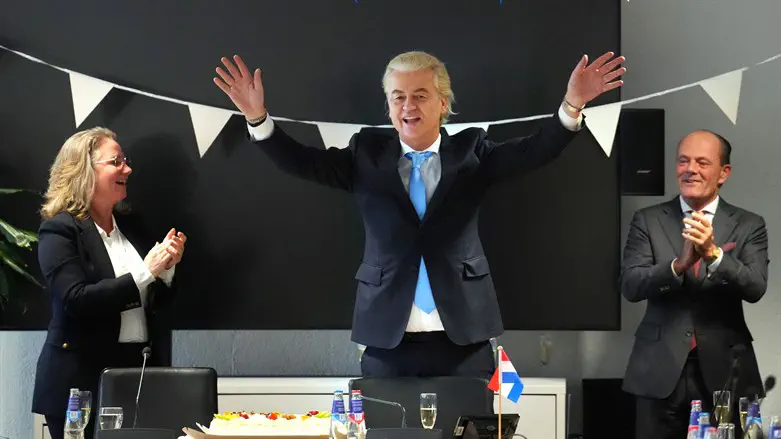

Wilders’s Party for Freedom (PVV) beat all predictions on Nov. 22, winning 37 of the 150 seats in parliament (or 23.6% of the vote) and far outstripping the second place Labor-Green alliance. After decades on the political fringe, Wilders has begun negotiating to form a government with himself as the next prime minister of the Netherlands.

The firebrand politician, whose “Netherlands first” rhetoric and blond-dyed bouffant hair earned him comparisons to Donald Trump, has long made anti-Islam policies a centerpiece of his agenda. Along with demanding a halt to the country’s “asylum tsunami,” he has called for a ban on Islamic schools, Qurans and mosques. A court found him guilty on insult charges after he led supporters in a chant for “fewer” Moroccans in the Netherlands at a 2016 campaign rally. In 2009, he was refused entry to the United Kingdom on the way to screen his film “Fitna,” which associated the Quran with terrorism and sparked international protests.

Following 13 years of a center-right government under former Prime Minister Mark Rutte, Wilders’ victory was broadly called one of the country’s “biggest political upsets” since World War II. His party’s surge came very late in the campaign, and Wilders himself didn’t seem to expect the result, reportedly renting a room as party headquarters for election night only three days beforehand.

That timing corresponds with weeks of public outcry over Israel’s bombardment of Gaza, which has sometimes morphed into aggression against Dutch Jews, according to Esther Voet, editor-in-chief of the Nieuw Israelietisch Weekblad (known in English as the Dutch Jewish Weekly).

“A few weeks ago, he only had between 13 and 17 seats,” Voet told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “This started a few weeks ago — since we’ve seen all the aggression in the streets — that he rose so much in the polls.”

Voet believes that Wilders benefited from a swell of open prejudice against Jews in the Netherlands. One watchdog documented an 818% increase in antisemitic incidents in October, ranging from assaults in schools to the tearing down of mezuzahs to swastikas painted on Jewish homes. Voet said some Jewish voters believed they would be protected by Wilders, who has touted his support for Israel as the Netherlands’ “close friend” and condemned antisemitism since Oct. 7.

Dutch Jews have historically opposed right-wing populist parties, but some shifted their views on Wilders sharply in recent weeks, said Voet. A Dutch Jewish Weekly poll in 2017 found that Jews were less open to voting for Wilders than the broader Dutch public was, with 10% of respondents expressing support for PVV compared with 15% of the public in general opinion polls. The most popular party among Jews was Rutte’s then-ruling People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy, followed by the center-left Labor Party.

“I have a lot of Jewish friends who are on the left side of the political spectrum, who voted for PVV because of what they saw in the last weeks,” said Voet.

Although he is not Jewish, Wilders volunteered on an Israeli kibbutz as a young man and is married to a Hungarian-Jewish former diplomat. He has also advocated for Israel’s settlements in the Judea and Samaria and suggested that all Palestinians should be relocated to Jordan.

Some Jewish organizations, including the Jewish news website Joods.nl, celebrated Wilders’ win as a victory for both Israel and Dutch Jews. On election day, the outlet posted a “Mazel tov” to Wilders alongside an Instagram post that read, “Hamas lost the elections.”

Lievnath Faber is the founder of Oy Vey, a progressive Jewish group that hosts events and discussions in Amsterdam. As antisemitic attacks surged in recent weeks, her colleague set up a WhatsApp “buddy system” for Jews across Amsterdam to check on each other and provide support.

“People are really needing to be together,” she told JTA. “For a lot of people, it’s very lonely to be Jewish now.”

However, Faber believes that Jews who voted for Wilders’ party were naively misguided by their “legitimate fears.”

“No matter what a politician might say — he might say he loves Jews and wants to protect Jews — we all know from our history, from our DNA that we are at risk when there is an extreme-right, anti-constitutional leader,” Faber said.

Jews constitute a small minority of about 30,000 people in the Dutch population of 17.7 million. Other voters who won Wilders the election say they were attracted by his promises to bring down taxes, healthcare and the cost of living. Some felt neglected by their government and resentful of migrants being granted homes amid the country’s housing crisis, according to Voet. Wilders also toned down his anti-Islam rhetoric during the campaign, although his manifesto still contains proposals to ban Qurans, mosques and Muslim headscarves.

Faber believes that Wilders’ victory has granted permission to a current of racism and xenophobia that abides in Dutch society — one that targets Muslims now, but might turn against Jews.

“If somebody in a public office voices things that are very racist, of course it also motivates other people to feel more comfortable doing that,” she said. “That’s one of the things that is scary about this win — what does it allow in the society?”