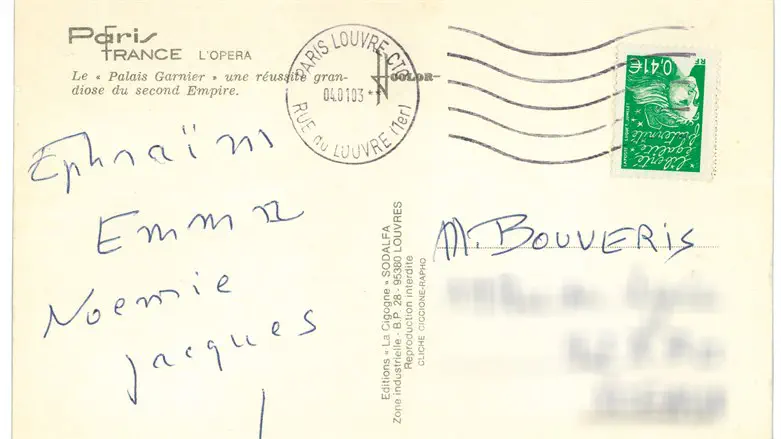

On a snowy day in 2003, Lélia Picabia received a postcard at her Paris home. Mysteriously, it contained only the first names of four of her ancestors who had perished in the Holocaust.

A linguist and Jewish mother of two, Picabia filed away the unsigned postcard in her correspondence archive. She found it vaguely threatening and wanted it out of sight.

But the postcard, featuring a picture of an opera house that used to be a former headquarters of the Nazi occupation of Paris, was never really out of mind. Questions about the author’s identity and intent kept nagging her.

Finally in 2019, Picabia and her daughter, author Anne Berest, 42, embarked on an investigation that not only likely solved the mystery — private detectives and a graphologist helped Berest identify the likely sender — but also helped them retrace their family’s hitherto unknown history.

The duo turned their research into a literary hit in “The Postcard,” an award-winning French-language bestseller published last year. The work of auto-fiction examines how the traumas of the Holocaust are playing out in the minds of French Jews today, as many of them question their future due to rising antisemitism.

The success of what Berest calls her anxiety-filled “identity research” is an “encouraging sign of awareness by society of the Holocaust amid troubling times,” she told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in an interview.

A gripping personal account styled as a whodunit, featuring private eyes and descriptions of Resistance-era tactics, the book unpacks the saga of a family that the Nazis and collaborators very nearly succeeded in wiping out. “The Postcard” won the prestigious Renaudot Prizen in the students’ literature category, the Sciences Politiques Student’s Prize and the first American version of the even more prestigious Goncourt Prize.

The critical acclaim isn’t unexpected of Berest, a seasoned writer who co-authored the 2014 international hit, “How to Be Parisian Wherever You Are,” a lighthearted ode to her city’s women. But critics were impressed by the range the new book demonstrated.

She was astonished and encouraged by the tens of thousands of book sales, and the many interviews and requests for public readings. This showed that “within French society, alongside the antisemitism, there are many who are interested in and empathetic toward Jews,” Berest said.

Books about the Holocaust certainly have a sizeable readership in France. “The Children of Cadillac,” another auto-fictional work spanning three Jewish generations by philosopher Francois Noudelmann, was published last year to critical acclaim and commercial success. (It was removed from the Goncourt shortlist for fear of a conflict of interest after Noudelmann’s girlfriend, who was on the award’s jury, wrote a scathing review of “The Postcard.”)

Tatiana de Rosnay’s Holocaust epic from 2006, “Sarah’s Key,” is one of the best-read novels written in French this century, with over 11 million copies sold in dozens of countries. A cinematic adaptation starred Kristin Scott Thomas.

But few Holocaust books in France have examined the role of Holocaust trauma in the thinking of French Jews today. Tens of thousands of French Jews have left the country for Israel alone in recent years following deadly Islamist attacks against them and hundreds of antisemitic assaults. Berest’s cousin also now lives in Israel.

The process of deciding whether to immigrate for safety is a recurrent, central theme in the book, both in the parts set before the Holocaust and after.

The book includes such conversations that Berest herself had with her friends and family — conversations that used to be rare 20 years ago but which have since become commonplace.

One such conversation happened in 2019 at a Passover seder dinner that she attended with her life partner, Georges, who is also Jewish.

“You are essentially living the prospect of reliving what your father experienced during the war,” Georges’ best friend, William, tells him during a conversation on whether the time has come to leave France due to antisemitism and the far-right’s electoral successes.

The book is personal, revisiting moments in Berest’s own life where she experienced antisemitism. A swastika was painted on her home in 1986, and later, a teacher who had lovingly mentored her suddenly began treating her coolly upon discovering her ancestors had died in Auschwitz.

It traces her childhood and youth, during which she had oscillated between shame and pride in her Jewishness, and it tells how she came to own her Jewish identity in recent years. (Berest frequents a Reform congregation now, though she says she is not very observant.)

The book also recounts Berest’s dilemmas as a parent upon hearing that her elder daughter, 10, is going through similar issues to those Berest had encountered growing up.

As Berest was conducting her deep dive into her family’s Holocaust history, her daughter remarked one day that she wished she was not Jewish because, “at school they don’t like Jews.” She was referring to a Muslim classmate who had excluded her from soccer matches during recess.

When Berest and Georges discuss whether to complain to the principal, Berest says, “I’m not going to report the son of an immigrant cleaning lady.”

Acknowledging this attitude was patronizing, she decided to speak with the principal anyway. But she came away shocked by his perceived reluctance to act.

Large parts of the book, which is 512 pages, are also devoted to telling the recent history of Ashkenazi Jewry through the biographies of Berest’s ancestors, beginning in 19th-century Russia. The plot runs through Poland, 1920s France, the United States, pre-state Israel, Nazi-occupied Europe, newly independent Eastern Europe and then back to modern-day Paris.

But the book begins with an attempt by Berest to explain to non-Jewish readers what being Jewish means to her. After an introduction to Judaism, the book quickly moves into the heart of some very parochial debates and discussions.

In one of them, a Jewish woman who is more involved in communal life than Berest, accuses the author over dinner of not “really being Jewish,” allegedly for not caring enough about antisemitism.

But caring, and caring enough to leave, are two different things, as Berest discovered in her research

“It became a traumatic question: Why did my family not leave?” said Berest, whose grandmother’s siblings and parents obeyed the authorities during World War II and were murdered. Her grandmother, meanwhile, escaped Nazi-occupied Paris for the countryside, where she survived in hiding. Still other relatives had left Europe before the war.

“Will I, who come from a family that failed to get out of harm’s way, be able to? I became obsessed by this question. It’s the book’s central interrogation,” she said.

Could she and French Jews be living presently through such a moment?

“I have moments of rising anxiety, which is undoubtedly in part inherent to my identity,” Berest said. “As a good Ashkenazi, anxiety is part of who I am.”