Rabbi David Rose serves as a rabbi in Edinburgh, Scotland and is a graduate of Torah MiTzion Stockholm (1997-1998)

The Torah instructs us to build a Sanctuary for G-d. The importance of this topic is such that it covers four and a half parshiot of the Torah, most of the second half of the Book of Exodus. The Sanctuary in its various forms, Tabernacle, Temple, or the mini-sanctuary of the synagogue, has been and remains a major, if not the major, focus of Judaism.

Yet Jewish history teaches us that this concept has had a negative as well as a positive influence on Jewish life. If we study Tanakh and examine Jewish history we fill find that the Temple has both contributed to the strengthening of Torah values but also to their undermining. It was from the Temple that the religious and political revolutions of righteous kings Yoash and Yoshiyahu emanated as well, of course, serving as the focus of the Maccabean revolt. On the other hand near the end of both previous Jewish states, the corruption of the Temple was a major factor leading to their destruction.

The same was true of the the Sanctuary at Shilo whose corruption led to defeat at the hands of the Philistines and its own destruction. As Jeremiah and other prophets warned, reliance on the Temple and its sacrifices without corresponding allegiance to the Torah and its mitzvot, will not save the state and its people but precisely the opposite.

So what makes the difference between a Sanctuary that fulfils its function as a source of salvation for the Jewish people and one that serves as a snare leading it on the wrong path? The simple answer is given in the famous phrasing of the Torah that the Sanctuary exists in order that G-d will dwell not in the Tabernacle but among ‘them’-the people. When G-d’s presence dwells among the Jewish people not just in the Temple, that is when it is fulfilling its function.

If we take a look at the holy items whose description precedes that of the actual structure of the Tabernacle we can discern the three main ways it is meant to positively interact with the Jewish people and lead them to G-d. The Ark and The Menorah are the symbols of the connection to Torah and its study and point to the central place the Sanctuary should take in the dissemination of Torah. The altar is the focal point for the regular service of G-d through sacrifice and the prayer that accompanied it. And, finally, the courtyard is the venue which enables bringing the people together in times of distress and joy, contributing to the unity of the Jewish people.

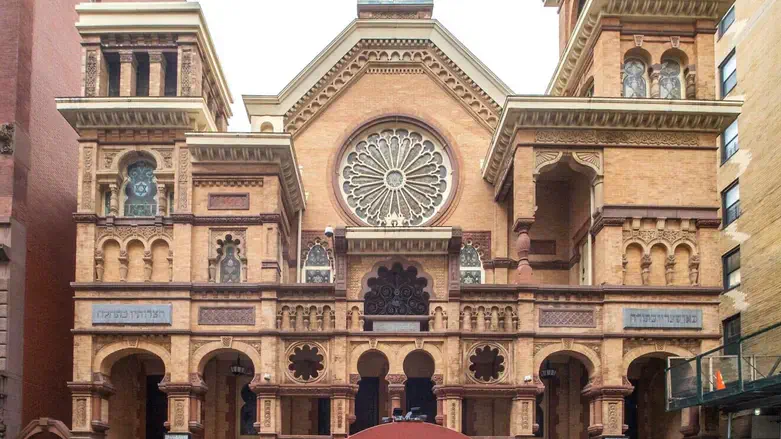

If we translate those three purposes of the Sanctuary into the institution of the Synagogue, the mini-Sanctuary, we see that our synagogues must be a Beit Midrash, a Beit Tefilah and a Beit Kenesset. This is especially true outside Israel where our synagogues are often the focal point of our communities, even for those Jews who in maybe in Israel would rarely or never enter one. They must be a Beit-Midrash, teaching Torah in all its aspects to Jews of what ever level of observance or knowledge. They must be an inclusive Beit Tefilah, combining traditional services with innovative techniques that enable everyone to connect to Jewish worship. And finally they must be a Beit Kenesset, a place where Jews of all stripes can find a welcoming, secure haven from the often hostile world outside. A place where Jewish identity can be freely expressed and strengthened.

As we read of the details of the Tabernacle, the first Jewish House for G-d, we must ask ourselves whether our present structures are fulfilling their purpose of causing the Divine Presence to dwell among the people. Are we spending resources on creating buildings or institutions or are we investing in the communities they are meant to serve? Those are the questions that have echoed throughout Jewish history since the construction of the first Tabernacle, and they are just as relevant today.

For comments: david.rose49@talktalk.net