Fern Sidman is Senior News Editor at Jewish Voice.

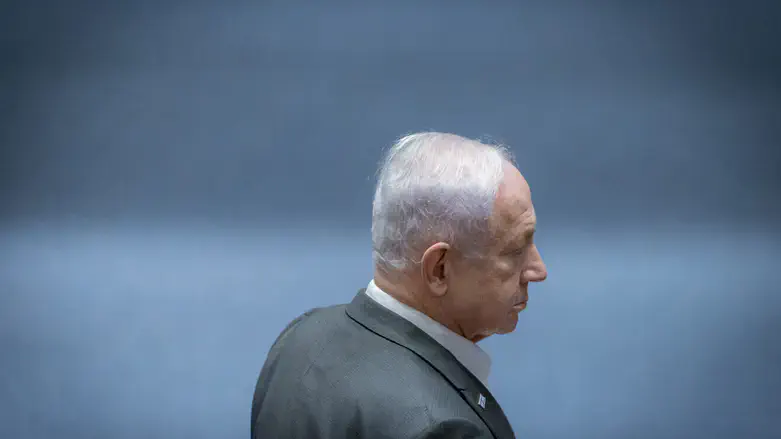

There are moments in the life of a democracy when fidelity to legal process, once a guarantor of legitimacy, begins to undermine the very confidence it is meant to sustain. Israel’s protracted corruption proceedings against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu have reached such a moment. Initiated in 2019 and sustained through a cascade of hearings, postponements, and procedural disputes, the case has metastasized into a permanent feature of the nation’s political climate.

Whatever one’s view of the allegations at inception, the trial’s duration and omnipresence have transformed adjudication into atmosphere-an ever-present fog that refracts governance through litigation and habituates citizens to a politics of perpetual suspicion.

Clemency exists in constitutional systems precisely to address such institutional impasses. It is not an abdication of the rule of law; it is law’s self-restraint. By design, the power of pardon recognizes that justice is not exhausted by procedure. It acknowledges that when legal processes become interminable, when they crowd out policy deliberation and corrode public trust, the public interest may be better served by closure than by the ritualization of prosecution.

In this sense, an immediate pardon for Netanyahu would be an act of statesmanship rather than indulgence-a recognition that democratic vitality depends not only on accountability, but on proportionality, timeliness, and civic equilibrium.

The substantive core of the case-often summarized in public discourse as revolving around gifts such as cigars and champagne-has, over time, assumed a symbolic weight far exceeding its original contours, especially since the recent revelations of then Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit. The longer the proceedings persist, the more they invite the inference that law has become an arena for political struggle by other means. This perception, whether embraced or contested, is corrosive.

Democracies depend on the belief that courts adjudicate discrete wrongs, not that they preside over permanent plebiscites on leadership. When trials become political weather systems, saturating the public sphere and shaping every debate, they cease to function as instruments of resolution and begin to operate as engines of polarization.

President Isaac Herzog’s refusal, thus far, to grant clemency to Netanyahu risks mistaking procedural endurance for moral clarity. The presidency’s constitutional role is not to mirror the judiciary but to integrate legal outcomes into the broader horizon of national interest. Clemency is the mechanism by which the constitutional order acknowledges that justice can be pursued to the point of counterproductivity. To withhold that mechanism in a case that has become structurally politicized is to allow process to eclipse purpose.

The rule of law is vindicated not by how long a prosecution can be sustained, but by whether the legal system restores clarity, fairness, and public confidence in the integrity of institutions.

President Donald Trump’s forthright defense of Netanyahu, and his public pressure on Herzog to grant a pardon, have forced this uncomfortable reckoning into the open. Trump’s rhetoric may be abrasive to diplomatic sensibilities, but its underlying claim merits very serious consideration: that leadership in moments of national strain should not be retroactively criminalized through proceedings that have become endless and politically central. In speaking up, Trump has articulated a widely shared democratic anxiety about the drift of legal process into political theater. His intervention underscores a principle too often elided in proceduralist discourse-that mercy, when exercised judiciously, is not the enemy of justice but one of its highest expressions.

The broader costs of protraction are evident. Endless litigation distorts governance by tethering the rhythms of statecraft to courtroom calendars. It encourages a culture in which policy is perpetually provisional, leadership permanently on trial, and public discourse reduced to forensic sparring. In a polity confronting acute security challenges and social divisions, this is a heavy tax on democratic energy. Clemency would not erase disagreement or silence critics; it would draw a line under a chapter that has consumed disproportionate attention and allow the political system to reorient toward substantive deliberation.

To be clear, advocating a pardon is not to deny the importance of ethical standards in public life. It is to insist that ethics, too, must be situated within a framework that preserves institutional legitimacy. Democracies do not flourish under perpetual prosecution; they flourish when legal accountability is firm but finite, when the law resolves disputes rather than perpetuates them. The presidency’s clemency power exists to mark that boundary. Its exercise here would reaffirm the separation between adjudication and governance, reduce the temperature of an overheated political climate, and restore a measure of civic trust.

History will judge leaders not only by their adherence to process, but by their capacity to discern when process has become an impediment to justice understood in the fullest sense-justice that preserves institutions, social cohesion, and democratic vitality. In this moment, clemency would be an act of constitutional maturity. It would close a chapter that has outlived its civic purpose and allow Israel’s political life to recover the oxygen of normal democratic contestation.