I had originally composed a somewhat light-hearted D’var Torah for Hanukkah, presenting a humorously anachronistic debate if the Seleucid Empire was anti-Semitic or merely anti-Zionist.

But in the shadow of the tragedy hurled against us in Bondi Beach, Australia, on the first night of the Festival - even before Hanukkah had begun in most of the world - I shelved my words.

The attack gave yet another definitive answer to the question of whether anti-Zionism is inherently anti-Semitic. This Hanukkah, while scores of Jews are sitting Shivah and scores others are still in hospital recovering, hundreds more traumatised, and the entire Jewish world in mourning, is not an appropriate time for such banter.

So I offer instead a far more sombre cogitation:

When King David composed the Book of Psalms, he wrote Psalms to celebrate, lament, prophecy, or commemorate any number of events.

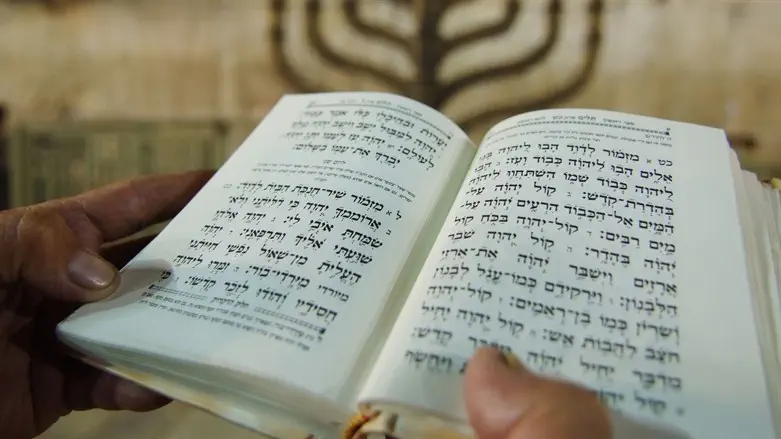

The thirtieth Psalm is headlined מִזְמוֹר שִׁיר חֲנֻכַּת הַבַּיִת לְדָוִד: “A Psalm, a Song for the Dedication of the Holy Temple by David”. This is the Psalm that the vast majority of Jewish congregations add to Shacharit (the Morning Service) every day during Hanukkah, as the Talmud (Soferim 18:2) rules.

King David yearned to build the Holy Temple, but G-d withheld that glory from him. But in his determination to participate in the construction of the Holy Temple, albeit vicariously and posthumously, he composed this Psalm which was to be sung at the Dedication of the Holy Temple which his son and successor, King Solomon, would build (following Rashi, Ibn Ezra, Radak, and others).

But there is something puzzling: this Psalm says nothing at all about the Holy Temple or sacrifices. It seems to contain nothing specifically relevant to the Holy Temple at all. So how and why is it appropriate for the Dedication of the Holy Temple?

Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch (Germany, 1808-1888) posits that this Psalm depicts the whole gamut of a lifetime of experiences - sickness and healing, suffering and deliverance, joys and sorrows. The Holy Temple was the physical expression of G-d’s presence in our midst (“They will make me a Sanctuary so that I will dwell in their midst” - Exodus 25:8) and of our aspirations to ascend to G-d.

Judaism teaches that all our experiences should bring us closer to G-d, so the Psalm which dedicated the Holy Temple reflects the whole range of experiences.

Indeed much of what King David describes in this Psalm portrays the dichotomies of life. He begins with the words:

אֲרוֹמִמְךָ ה' כִּי דִלִּיתָנִי וְלֹא־שִׂמַּחְתָּ אֹיְבַי לִי:

This is invariably understood to mean:

“I will exalt you, O Hashem, because You have raised me up, and not made my enemies rejoice over me”.

This is a perfectly reasonable understanding of King David’s words. However the word דִלִּיתָנִי could equally be from the root דַּל, meaning “poor”. Hence I suggest an alternative understanding:

“I will exalt you, O Hashem, even though You have impoverished me, and You have not made my enemies rejoice over me”.

Or more pointedly:

“I will exalt you, O Hashem, because even though You have impoverished me, you have not made my enemies rejoice over me”.

King David recognised that his sufferings were ultimately for the good, part of G-d’s infinite and eternal plan. And however much he suffered, at least his enemies would have no schadenfreude.

There is no greater suffering than being persecuted and hounded by enemies who rejoice in their persecution of Jews. We have seen the ecstasy of hate as our enemies slaughter us. We have seen it all too often: Whether in Nazi-occupied Europe or on Shavuot 5741 (1941) in the Farhud, the pro-Nazi revolution in Iraq or in Israel on Sn’mini Atzeret/Simchat Torah two years ago or in Bondi Beach as Hanukkah was beginning -

- it wasn’t just the fact of being massacred; it was the humiliation of seeing the murderers exulting in Jewish deaths.

King David experienced the same frustration and humiliation: he was born at a time when Israel was weak in its own Land, a disunited nation, a loose federation of Tribes, periodically harassed and persecuted by Philistines, Canaanites, Amalekites, Midianites, and other assorted enemies.

But then Saul was anointed King over Israel, and for the first time the Tribes were all united under a single monarch. There were still wars to be fought, the Philistines and Amalekites would still defeat Israel in battles - but at least Israel was united, and the halcyon era was about to begin.

The Philistines would still defeat Israel, King Saul and his three sons would die, and Israel would be plunged into a civil war - but when King David became King the nation immediately became more united and stronger than ever before.

The enemies of Israel, so confident just a short time ago, would have little cause for mirth after that. They would swiftly understand the foolishness of attacking Israel.

The same happened millennia later when the Seleucid Empire conquered Israel in 198 B.C.E. They seemed undefeatable, the mightiest empire in the world. Israel was subjugated, oppressed and humiliated. It was among the darkest days that Israel had seen since Egyptian slavery.

And then in Modi’in, a sleepy and obscure village 25 km (15 miles) north-west of Jerusalem, an almost unknown Priest, Matityahu, defied the local Seleucid tyrant - and history changed dramatically.

In historical terms, the Maccabean Revolt was the beginning of the end of the Seleucid Empire. Its power began waning - not only in Judea, but also in other provinces. The Maccabean victories over the Seleucids shattered their veneer of invincibility, and inspired other conquered nations to take up arms and fight for their freedom too.

Over the next few decades, as Shimon the Kohen Gadol (High Priest) and after him his son Yochanan Hyrcanus I drove the Seleucids out of the central region around Jerusalem, and then expanded westwards up to the Mediterranean coast, eastwards to the River Jordan (thus connecting with the trans-Jordanian area), southwards as far as the edge of the Negev Desert, northwards to the Galilean hill country, and then even farther eastwards into Idumæa in trans-Jordan (the south-west area of the present-day kingdom of Jordan), the Seleucids also faced insurrections in Parthia (modern-day Iran), Armenia, Cappadocia (modern Anatolia), and Pontus (southern coast of Black Sea, in modern north-east Turkey).

All these nations had (arguably) been inspired by the Maccabees to take up arms against the Seleucids. Indisputably, the sheer ferociousness and strategic brilliance of the Maccabees forced the Seleucids to divert personnel away from those areas in order to contend with the Jewish forces.

By 100 B.C.E., the once-formidable Seleucid Empire had shrunk to Antioch and some Syrian cities, and a few decades later it finally collapsed. The Maccabees had defeated the Seleucid Empire by imposing an impossibly heavy price-tag on its anti-Jewish tyranny.

The Seleucids had little to celebrate.

As we say every day during Hanukkah: בַּיָּמִים הָהֵם בַּזְּמַן הַזֶּה - as in those days, so too at this time: we all saw the sickening schadenfreude of the genocidal psychopaths a little over two years ago, as they celebrated the sadistic mass-murder and torture that they inflicted on the Jews.

Not many Gazans are still celebrating. They have learned the foolishness of attacking Israel.

But it is only in Israel that we can seize our own destiny so openly. Not in countries of exile: not in America, not in Australia, not anywhere in exile.

King David continued:

“In the evening one lies down weeping - but in the morning is joyful song!” (Psalms 30:6). Evening represents the darkness of exile - and morning represents the light of Redemption. When we return home to Israel, our weeping becomes joyful song:

“You have transformed my mourning into exuberant dance, You have released me from my sackcloth, and You have surrounded me with joy!” (v. 12).

This is the glorious that awaits us here in the Land of Israel. There is no guarantee that our enemies will no longer attack us here in Israel - but at least their sadistic joy is guaranteed to be short-lived and thoroughly repaid.

As noted above, the usual understanding is that King David composed this Psalm in anticipation of the first Holy Temple that his son King Solomon would build. But the Ibn Ezra (Rabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra, Spain, Morocco, England, Israel, and France, 1092-1167) adds additional possibilities:

“There are those who say that David ordained that the Temple Singers would play this Psalm at the Dedication of the First Temple; and there are those who say that it is for the Dedication of the Second or Third Temples, because the days of exile resemble days of sickness”.

This is why he wrote the words, “Hashem my G-d, I cried out to You and You healed me” (v. 3); because the return to Zion from exile is the equivalent of being healed from sickness.

Several Midrashic sources tell us that there are ten great Songs in history:

The first was while we were yet in Egypt (alluded to in Isaiah 30:29);

The second was the Song at the Red Sea (Exodus 15);

The third was at the Well (Numbers 21:17);

The fourth was Moshe’s Song at the end of his life (Deuteronomy 31);

The fifth was Joshua’s peroration (Joshua 10:12);

The sixth was Deborah and Barak’s Song of victory (Judges 5);

The seventh was King David’s Song of victory (2 Samuel 22);

The eighth was Psalm 30;

The ninth was the Song of Songs composed by King Solomon;

The tenth and last will be the new Song that we will sing in the time of Mashiach, “Sing a new Song to Hashem for the wonders He has wrought” (Psalms 98).

(Tanhuma, Beshallach 10, and compare Lekach Tov, Shemot 15:21 and Mechilta de-Rabbi Yishmael, Beshallach, Masechta de-Shira 1).

So great is Psalm 30, which prophetically celebrates the Dedication of the Holy Temple, that it is one of the ten great Songs in our history.

Whether the Dedication of the first Holy Temple by King Solomon, or the second Holy Temple in the days of Ezra, Nehemiah, and Zerubavel, or the third Holy Temple in the future time, the joy will be so great as to wipe away all our sorrows and tears from the exile.

It will be a time when no enemy of Israel will have any rejoicing at all.