In memory of Mikki Sunshine, Mekimiya bat Peisha Beila, who passed away today in Hadassah Hospital, Jerusalem.

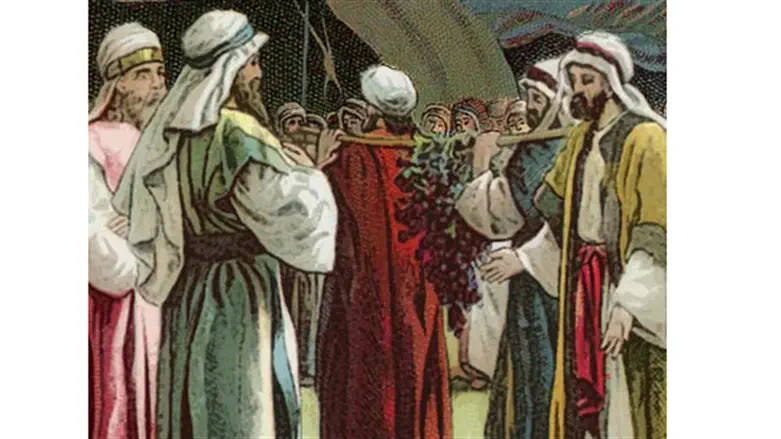

“Send for yourself men who will spy out the Land of Canaan”, G-d told Moshe at the beginning of Parashat Shelach Lecha (Numbers 13:1-2), and at this stage, it appears that the initiative to send these twelve spies came from G-d.

But this isn’t what actually happened, as we find out some thirty-eight-and-a-half years later, when Moshe would remind the next generation of their fathers’ sin:

“You – all of you – approached me, saying: We’ll send men ahead of us, who will spy out the Land for us and will bring us a report about the way on which we will ascend, and the cities to which we will come. This seemed like a good idea to me, so I took twelve men from you, one man for each Tribe” (Deuteronomy 1:22-23).

So actually, the initiative to send the spies came from the people, Moshe confirmed it, and G-d gave His permission. Permission, not active agreement; He certainly didn’t recommend it.

Therefore the slightly unusual wording, שְׁלַח־לְךָ אֲנָשִׁים, “send to yourself men”, the additional word לְךָ connoting “on your cognisance; I am not ordering you, but if you want to, then send them” (Rashi ad loc.),

Today we have the benefit of hindsight, we know exactly how disastrous this decision was.

…or do we? Do we really fully understand the full consequences?

The Ba’al ha-Turim (Rabbi Ya’akov ben Asher, Germany and Spain, c.1275-1343) notes that the gematria (numerical value) of the word שְׁלַח (send) is 338, an oblique reference to the year 3338, the year in which Babylon conquered Israel, destroyed the Holy Temple, and hauled the majority of the population into slavery and exile in Babylon.

The inference is that 889 years later, the nation was still paying for the sin of the spies. They delivered their evil report on the 9th of Av, and on the same date 889 years later, Babylon destroyed the Holy Temple and extinguished Jewish independence in the Land of Israel.

And half-a-millennium later yet, the Romans destroyed the second Holy Temple on the same date.

It wasn’t just that one generation which carried the punishment for rejecting the good Land which G-d had decreed for His people. It was curse which resounded – and still resounds – throughout the generations.

Last week, commenting on Parashat Beha’alot’cha (https://www.israelnationalnews.com/news/391839) I cited an episode in the Talmud (Yoma 9b), which I repeat here:

“Reish Lakish [Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish] was swimming in the River Jordan, and Rabbah bar Chanah came and offered him his hand [to help him out of the water]. [Reish Lakish] said to him: By G-d! I hate you [the Babylonian Jews as a whole, who did not come back in the days of Ezra, and thereby prevented the Shechinah (the Divine presence) from returning and once again infusing the rebuilt Holy Temple – Rashi]. For it is written: ‘If she be a wall, we will build upon her a turret of silver; if she be a door, we will enclose her with boards of cedar’ (Song of Songs 8:9) Had you made yourselves like a wall and all come up in the days of Ezra, you would have been compared to silver, which no rottenness can ever overcome. Now that you have come up like doors [a double door in a gate, where one door can be open while the other one remains closed; thus you Babylonian Jews only partially came back to Israel – Rashi] you are like cedar-wood, which rottenness overcomes”.

When Koresh (Cyrus) granted permission to the Jews of his empire to return to Israel, only 42,360 came in the first wave (Ezra 2:64). The majority of Jews were quite happy to remain in exile – and for this, like with the generation of the desert, there were consequences; deeply unpleasant consequences.

Let us return to a generation before the spies:

Several Talmudic and Midrashic sources (Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer 48, Targum Yonatan to Exodus 13:17, Targum to 1 Chronicles 7:21, Shemot Rabbah 20:11 et al.) record that 30 years before the Exodus, 200,000 warriors of the Tribe of Ephraim decided that the time of redemption had come, and they left Egypt.

As sons of Joseph, who had been ruler of Egypt, they saw themselves as royalty, and believed that it was their role to seize the initiative and lead the nation out of slavery and into Israel.

They knew – as did every Jew – that G-d had long since told their forefather Abraham that the nation would be oppressed for 400 years (Genesis15:13), and they dated the 400-year countdown from the day that G-d had made this promise. They didn’t realise that the 400-year countdown actually began 30 years later, the day that Isaac was born.

So they burst their way out of Egypt 30 years too early, trekked across the Sinai Desert, and reached the Gaza region – and there, the Philistines slaughtered them all.

True, a tragic end to these brave warriors – but at least they merited to enter the Land of Israel, which even Moshe was denied.

A millennium later, the Prophet Ezekiel saw and recorded his famous vision of the valley of the dry bones (Ezekiel 37). As he watched, the bones rose u and came back to life. These were the bones of hose warriors of Ephraim.

So even though they were slaughtered, they were destined to be the first ones to be resurrected.

There were consequences for these warriors of the Tribe of Ephraim – consequences for escaping Egypt ahead of G-d’s schedule, and also consequences for their determination to reach Israel.

A generation later, the Torah hints at the Tribe of Ephraim’s special status exquisitely subtly, in the way it records the name of the Prince of their tribe: Most of the Princes’ names are recorded in the same way:

לְמַטֵּ֣ה שִׁמְע֔וֹן שָׁפָ֖ט בֶּן־חוֹרִֽי:

“For the Tribe of Simeon – Shafat son of Hori.”

לְמַטֵּ֣ה יְהוּדָ֔ה כָּלֵ֖ב בֶּן־יְפֻנֶּֽה:

“For the Tribe of Judah – Caleb son of Yeffuneh.”

And similarly for most. However the Tribe of Ephraim is recorded differently:

לְמַטֵּ֥ה אֶפְרָ֖יִם הוֹשֵׁ֥עַ בִּן־נֽוּן:

“For the Tribe of Ephraim, Hoshea Bin-Nun.”

The cantillation-marks (the “notes”) are different. Most of the Tribes’ names have a זָקֵף-קָטֹ֔ן (zakef-katan), which is a separative note, which I have attempted to convey with the dash (“For the Tribe of Simeon – Shafat son of Hori”).

However the name Ephraim is marked instead with a טִפְּחָ֖ה (tip’cha), indicating less of a break, which I have attempted to convey with a comma (“For the Tribe of Ephraim, Hoshea Bin-Nun”).

This indicates a closer connexion between Hoshea Bin-Nun and his Tribe than between the other Princes and their respective Tribes.

What distinguished Ephraim, throughout the history of the Tanach, was their unwavering devotion to the Land of Israel, their determination to fight for it.

And this, too, had consequences: of all the Tribes, Ephraim was G-d’s most beloved. In his heart-rending depiction of Rachel’s inconsolable weeping for her exiled children and the eventual the Return to Zion, the Prophet Jeremiah gives us G-d’s words:

“Is Ephraim my beloved son? Or a delightful child? – That whenever I speak of him, I remember him ever-more; therefore My innermost being yearns for him, I will have eternal mercy on him, says Hashem” (Jeremiah 31:19).

And a later Prophet depicts the eventual reuniting of the two kingdoms, Israel and Judah:

“The Word of Hashem came to me, saying: So now, Son of Adam, take to yourself one stick, and inscribe upon it ‘For Judah and for the Children of Israel his comrades’; and take one stick and inscribe upon it ‘For Joseph, the Stick of Ephraim, and the entire House of Israel, his comrades’; then bring them near to yourself, as one stick, and they will become united in your hand” (Ezekiel 37:15-17).

So beloved was the Tribe of Ephraim that they became the epitome of all the Tribes, particularly in the time of the Return to Zion and the Ingathering of the Exiles.

There are consequences to rejecting the good Land which G-d gave us; just as there are consequences to demonstrating our love and devotion to it.

If only the Jews would have listened to Joshua and Caleb instead of the other ten spies, if they would have seized the opportunity to enter the Land and possess it, then the 9th of Av would have become a day of eternal celebration, instead of a day of mourning and disaster.

If only the Jews in the days of Koresh (Cyrus) would have seized the opportunity to enter the Land and possess it, then they would have brought the final redemption some 2,400 years ago.

But they didn’t, and we live (and die) with the consequences until today.

When the Jews of a thousand years in the future look back at our present-day reality, what will they say and write about our generations? What consequences will we, today, bequeath to our ancestors?

What will the Reish Lakish of the year 6000 say to the descendants of the Jews of today’s America?

The answer is not yet written. But every Jew in the world today has his or her share in writing that answer.