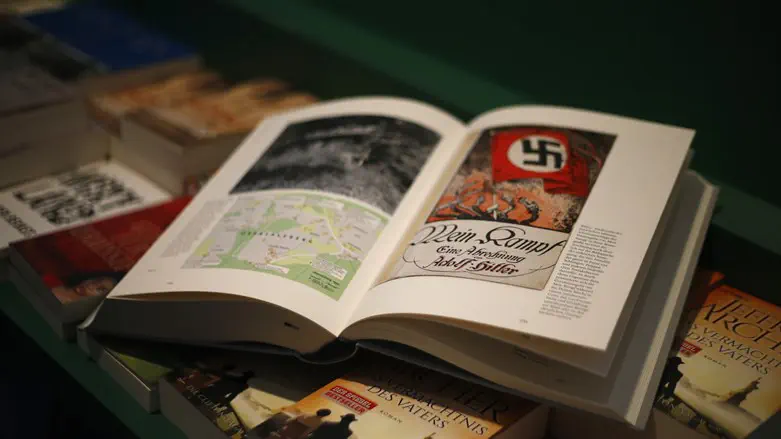

What’s Mein Kampf doing in Gaza?

Israeli President Isaac Herzog has revealed that an Arabic-language copy of Adolf Hitler’s notorious manifesto of antisemitism and militarism was found in a Gaza apartment that Hamas was using as a base of operations. The terrorist who was studying it wrote notes in the margins.

Sixty-seven years ago, another Israeli leader announced the discovery of copies of Mein Kampf in the possession of a different enemy. On December 5, 1956, Golda Meir, then foreign minister of Israel, spoke before the General Assembly of the United Nations to explain why her country had been compelled to launch a pre-emptive strike against Egypt a week earlier. Her remarks included a surprising reference to Hitler’s book.

Ever since Israel’s War of Independence concluded in 1948, Egypt had been preparing its next attempt to destroy the Jewish State, Meir explained. There had been constant attacks by terrorists based in Egyptian-occupied Gaza, relentless economic warfare (an early version of the BDS movement), and a massive arms deal between Egypt and the Soviet Union. “For eight years,” she said, “Israel has had no respite from hostile acts and loudly proclaimed threats of destruction.” The Egyptians left Israel no choice but to strike first, or face annihilation.

Foreign Minister Meir saw a connection between the Holocaust and Egypt’s aggression. “The concept of annihilating Israel is a legacy of Hitler’s war against the Jewish people,” Meir said. “It is no mere coincidence that the soldiers of [Egyptian dictator Gamal Abdel] Nasser had an Arabic translation of Mein Kampf in their knapsacks.”

Hitler wrote Mein Kampf (My Struggle) while in prison after his failed coup, the Beer Hall Putsch of 1923. With its numerous references to internal German controversies and domestic policy matters, the book might not seem to have any natural appeal to non-Germans. But after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, Mein Kampf attracted widespread international attention, both from those who feared him and those who admired him.

The book’s extreme antisemitism and advocacy of German territorial expansion attracted sympathetic interest in the Arab world. Extracts appeared in the Arabic press in Iraq and Lebanon in 1934. Unauthorized translations were published in Egypt in 1937 and Palestine in 1938. According to a Jewish Telegraphic Agency report at the time, the editor of the Palestinian edition “carefully purged the passage in which the Arabs are graded fourteenth on the racial scale.”

As part of the deNazification process implemented in Germany by the Allies after World War II, the Nazi Party was banned, public display of the swastika was prohibited, and the printing of Nazi literature, including Mein Kampf, was outlawed. It was only due to a legal technicality—the expiration of the book’s copyright—that as of 2016, selling or purchasing Mein Kampf is no longer a crime in Germany.

The question of the copyright to Mein Kampf set off a curious legal battle in the United States in 1939 involving Alan Cranston, the future U.S. senator. Cranston, who was fluent in German and had visited Germany in 1936 as a journalist, noticed that the American edition, published by Houghton Mifflin, omitted the most extreme and violent passages from the original edition.

Determined to expose the real Hitler to the American public, Cranston set to work preparing a condensed tabloid edition that highlighted the omitted sections. One of Cranton’s secretaries misunderstood the nature of the project and reported to the Anti-Defamation League that Cranston was preparing Nazi propaganda. After realizing what Cranston actually was doing, ADL staffer Benjamin Epstein assisted him with the research.

Cranston called it a “Reader's Digest-like version” of Mein Kampf. Priced at just ten cents, the tabloid sold 500,000 copies in ten days, according to Cranston. While Houghton Mifflin was paying Hitler royalties from sales of its sanitized version of Mein Kampf, the Cranston edition carried a blurb which read “Not 1 cent of royalty to Hitler,” and pledged to send the profits to refugees fleeing the Nazis. “Fritz Kuhn’s American Nazis threw stink bombs at newsstands selling it in Yorkville and St. Louis,” Cranston biographer Eleanor Fowle wrote.

Houghton Mifflin sued Cranston for copyright infringement. Cranston’s novel legal defense (recounted in my forthcoming book, Whistleblowers: Four Who Fought to Expose the Holocaust to America) was unsuccessful; he was ordered to halt publication and destroy all existing copies of his edition of Mein Kampf.

In more recent years, Hitler’s manifesto has continued to enjoy considerable popularity in the Arab world. In 1982, Israeli troops found numerous Arabic-language copies of Mein Kampf in PLO strongholds that they overran in Lebanon. In 1999, the French news agency AFP reported that it was a bestseller in the Palestinian Authority-controlled territories, according to sales figures compiled by the most popular bookstore in Ramallah, the PA capital.

Although it is now nearly a century old, the fiery message of Mein Kampf evidently still appeals to those who share at least some of the sentiments of its author.

First published in the Jewish Journal of Los Angeles

Dr. Medoff is founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies and author of more than 20 books about Jewish history and the Holocaust. His latest is America and the Holocaust: A Documentary History, published by the Jewish Publication Society & University of Nebraska Press.