They are living a benign dream in Goshen, Egypt. Jacob’s seed have yet to encounter Balaam – the name would mean nothing to them. It will be hundreds of years before it does, and then it will be contiguous with trouble. Balaam will be more than known. When a stored up grievance gushes out he will entice the tribes into calf worship and internecine killing. He will make God want to wipe the whole lot out. There will also come a time when the Israelites parody the clown God made a donkey make of him. In a roundabout way Balaam will have the last laugh. The nation he set out to curse and got paid a king’s ransom to curse, recites to this day the divine blessing he gave it

Is there nothing, people ask, that Balaam can’t be or can’t do. Yet to look at him…That crooked back and missing eye and weak knees that bend under the strain of a corpulent belly: surely Balaam, son of Be-or the beast, son of Laban the swindler must be hard put to swat a fly.

A knack for dire mischief making has brought him together with a priest from Midian and a magnate from Canaan and the King of Egypt. They have to make the fate of a multitude, grouped into thirteen prolific tribes, fit their crime. Egypt had offered the circumcised Hebrews a helping hand. They took half the body and corrupted the soul. Jacob’s brood have turned Goshen into a Hebrew enclave. The king assembled a brains trust to approve the remedy that came to him in a dream.

He kept three wise men waiting half the morning in a stifling anteroom ill served by an unapologetic under-butler. To make the ordeal tortuous, each one had scant respect for the reputation of the other two. By the time the great doors opened and the chamberlain signalled them into the interview chamber, their brows beetled with hostility.

How copper coloured and puerile Pharaoh is, like a figurine on dry parchment; how liquid his flat grey eye. There is a crowd of attendants behind the royal chair; at a signal from the king they retire to different corners – adult goats protecting a kid. Slow finger motions beckon them to three chairs around the slippered feet. They feel at pains not to disturb the quiet when taking their seats. The king inclines his head and the Chamberlain melts backwards out the door.

Pharaoh inspects his fingernails. ‘Long travels, ‘he says. You weren’t expected so early.’ He waits for some gratifying reaction. The brains trust nod, taking it for granted that he knew how long they had been waiting.’ Well, he says, ‘the conditions were favourable – I’m glad.’

Camels. Dry wells. Sand storm. Desperate bandits. They’d set out half a week ago – not that they complain – at the king’s summons.

The chairs are marble, with the Pharaoh image inlaid in gold. He’s the new Pharaoh, the one who forgot Egypt’s two hundred year old debt to Joseph. He has forgotten but not forgiven the son of Jacob for bringing the whole family up from Canaan to settle Egypt. To him it feels the whole country is occupied, but he means Goshen, the part that a Pharaoh of old promised Abraham to compensate for kidnapping Sarah; a fertile country watered by the Nile for a stolen wife.

The meeting begins obliquely, as formal meetings can do. Balaam is an object of Pharaoh’s curiosity. He can’t keep his eyes off him. Balaam chuckles as he jabs a finger in his fiery eye socket. ‘Your majesty, the Philistine who gouged it out did me a favour.’ The king shrinks back. ‘Don’t feel sorry – it’s been a help rather than a handicap.’

Job leans forward to take a closer look. Now he’s got everyone looking at him. “I tell no lie,’ he says. ‘For my trade the left eye is all I need.’

Job gives the eye a close look and shakes his head. ‘What do you mean all you need?’

‘My lord, the right eye is for seeing the good side of character, and that has the effect of weakening a curse. The left eye discerns the bad in people, and the effect of that gives strength to a curse. Not one curse has flopped since the eye came out.’

Jethro sternly says, ‘No more clients for blessing, I’ll be bound.’

‘They, my lord, were never a big part of my practice.’

Jethro is disgusted. ‘Well,’ he says, ‘I understand why you are so pleased. It takes more work to do good than to do evil. Your supplier is who – Ashmedai, king of the demons?’

The two don’t get on. The problem is their commonality, both outcasts from the family tree of Abraham. Jethro – Reguel the Priest they call him in Midian – is from the spawn of Abraham’s concubine, Katura; Balaam, a Moab, is from the incestuous spawn of Abraham’s nephew, Lot.

But their host is getting fidgety. ‘Look now my lords,’ says the king when he’s got their attention, his voice playing up and down the scale. ‘You know the situation. It has got out of control. You know the Israelite. Give him a hand and he takes your arm.

‘And that’s the best that can happen,’ Balaam says.

The king likes it. ‘My lord, you learnt well on the knees of your grandfather.’

‘Twenty years, your majesty. Twenty years Laban employed and set up Jacob – who then decamped even with an idol collection. I wasn’t born yet.’

‘If only you had been, my lord. Jacob would have gone through life cursed instead of blessed.’

‘The crux, your majesty, of your population problem.’

Pharaoh smiles. He has a pert mouth and red lips, like a girl’s. ‘It will test your powers to the utmost.’

‘That bad, your majesty?’ Job says.

It is worse, and Pharaoh lays it out. The tone of the pubescent king modulates between high, broken and thin. Goshen, he says, is blocked with Israelites and their animals. It’s a plague of epic proportions. Egypt is a heartbeat away from an insurrection. In the best case. The worst case would be the Israelites aiding and abetting neighbouring kingdoms. The new census presents a frightening picture: three million not counting the young. That birth rate can’t be allowed to go unchecked. The wives drop litters every time. Hebrew speaking loiterers jam entire thoroughfares – a miraculous life force.

Job the business genius says, ‘Harness it. Your majesty put that force to work. You got a precious labour resource. Projects and more projects. Make Egypt a showcase; and keep the breeders too hard at work to want to procreate.’

The double-hit scheme was so good it took a while to get over the shock. In the quiet Jethro’s self-protest was audible.

‘Of course,” Balaam says, master Job is not advocating forced labour. Nothing like slavery. It would be a test of fealty to Pharaoh, of gratitude to the host country. No one hurt and all benefit.’

Job adds, ‘You’d start the breeders on a trial project. Get the feel and reaction. One baby step at a time.’

Jethro sits bent, studying the floor at his feet and cracking his hairy knuckles. Job puts a hand on his shoulder. Jethro: ‘Come outside, you two.’

‘Your majesty,’ Job says, can we break. My lord Jethro suffers giddiness. A turn in the gardens …’

‘I thought it would come to this,’ Jethro swears as they follow the river walk.

‘Nevertheless you came,’ Balaam says bitingly.

‘Not to nod at everything you and the boy king want.’

Job says, ‘Do we really want to cross Pharaoh? His mind is made up. Kings must have their way. You might as well try turning a donkey cart in a tight alley. What good will it do, backing down? We’ll be thrown in prison. Going with the plan might allow us to modify the gaudy bits’.

Balaam who never liked modifying anything, displays a set of grey square teeth. ‘Let’s be clear. What made you, my lord Jethro, obey the king’s summons? Was it popularity you wanted, or to be useful? Pull out now and you forfeit both.’

A flash of anger. ‘What made me? I hoped to stop an enslavement. God made a promise to Abraham. His progeny would become like the stars in the universe. Not the king and not you, dear Balaam, can void a promise God makes.’

More to come.

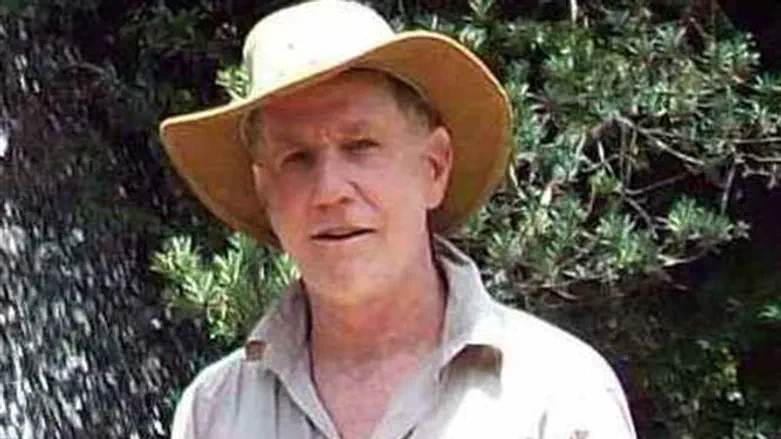

Steve Apfel is an economist and costing specialist, but most of all a prolific author of fiction and non-fiction.