The Shabbat which either coincides with or immediately precedes Rosh Chodesh (the first day of the Hebrew month) Nissan is called שַׁבַּת הַחֹדֶשׁ, Shabbat Ha-Chodesh.

The name is derived from the Maftir, the reading which concludes the Torah-reading. Instead of being a repetition of the final several verses of the Torah-reading (as it usually is), the Maftir for this Shabbat is instead Exodus 12:1-20:

“Hashem spoke to Moshe and Aaron in the land of Egypt, saying: הַחֹדֶשׁ, this month will be the first of your months…”

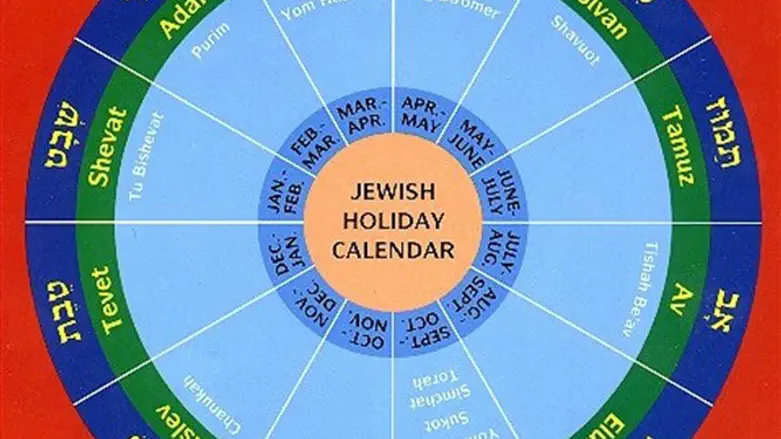

This is the basis of the Jewish calendar: it is the commandment that we calibrate our own calendar, with the month of Aviv (Nissan) as the first month. It also implies obliquely our entire calendar-system: the months are calibrated from new moon to new moon, and the year has to be calibrated such that Nissan invariably falls in the spring-time, hence the system of leap-years in which we have an extra month.

In order to understand the significance of having our own calendar, let us go back to the day that G-d gave this mitzvah:

It is the first of Nissan in the year 2448 (1312 B.C.E.). Nine of the Ten Plagues have struck Egypt, and only the tenth, the Slaying of the Firstborn, the most devastating Plague of them all, is yet to come. But that is still two weeks in the future.

The Jewish nation is poised on the very threshold of freedom. After 210 years of exile in Egypt, we are just two weeks away from the Exodus. The slavery is already a thing of the past, a recent and bitter memory, but we are still imprisoned in Egypt, as yet unable to leave.

And it is now that G-d gives us our first-ever national Commandment: “Hashem spoke to Moshe and Aaron in the land of Egypt, saying: This month shall be the head of your months – it will be the first of the months of your year”.

It is of course deeply significant that establishing our own calendar marks the end of slavery: a slave needs no calendar, no clock. A slave has no need to calibrate or to measure time. He eats, sleeps, works, lives his entire life according to his master’s schedule and commands.

And the corollary is that a free nation needs its own calendar to govern its own life.

And so it is no coincidence that it is specifically Pesach, the Festival which celebrates our freedom from Egyptian slavery, which calibrates all of our Holidays.

Almost three-quarters of a millennium ago, the Ba’al ha-Turim (Rabbi Ya’akov ben Asher, Germany and Spain, c.1275-1343) designed a simple method of calculating which day of the week any given Festival will fall on by its relation to Pesach (Arba’ah Turim, Orach Chaim 428:5).

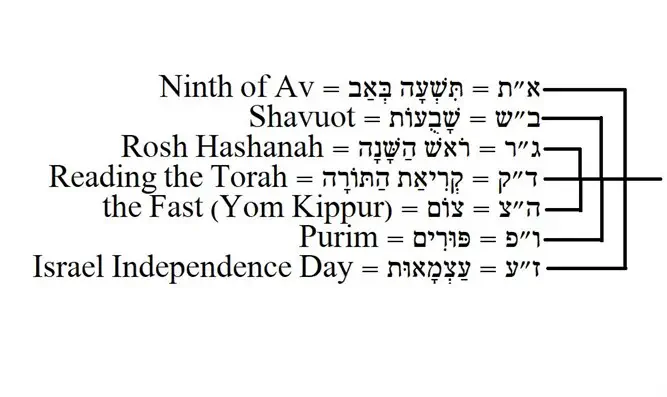

He used the א"ת ב"ש (pronounced “atbash”) system of alphabetic manipulation: in the א"ת ב"ש system, the first letter (א) interchanges with the last letter (ת); the second letter (ב) interchanges with the second-from-last letter (ש); the third letter (ג) interchanges with the third-from-last letter (ר), and so on.

And so in the א"ת ב"ש system, the seven days of Pesach are represented as:

א – ת

ב –ש

ג –ר

ד –ק

ה –צ

ו –פ

ז –ע

The right-hand column contains the first seven letters of the Hebrew alphabet; the left-hand column contains the final seven letters, in reverse order.

The seven lettersא, ב, ג, ד, ה, ו, ז represent the seven days of Pesach. And their corresponding letters with which they interchange represent the Festivals as each is the first letter of the name of one of the Festivals or its main characteristic.

א"ת = תִּשְׁעָה בְּאַב ninth of Av))

ב"ש = שָׁבֻעוֹת (Shavuot)

ג"ר = רֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה (Rosh Hashanah)

ד"ק = קְרִיאַת הַתּוֹרָה (Reading of the Torah, meaning Simchat Torah)

ה"צ = צוֹם (the Fast, meaning Yom Kippur)

ו"פ = פּוּרִים (Purim)

ז"ע = ?

This means that in any given year: –

א, the first day of Pesach, falls on the same day of the week as ת, the ninth of Av, four months later. (This year, first day Pesach is Motza’ei Shabbat/Sunday, and the 9th of Av will likewise be Motza’ei Shabbat/Sunday);

ב, the second day of Pesach, falls on the same day of the week as ש, Shavuot, seven weeks later. (This year, second day Pesach is Sunday night/Monday, and Shavuot will likewise be Sunday night/Monday);

ג, the third day of Pesach, falls on the same day of the week as [the first day of] ר, Rosh Hashanah, five-and-a-half months later;

ד, the fourth day of Pesach, falls on the same day of the week as ק, Simchat Torah, half-a-year later;

ה, the fifth day of Pesach, falls on the same day of the week as צ, Yom Kippur, half-a-year later;

ו, the sixth day of Pesach, falls on the same day of the week as פ, Purim, a month before Pesach. (This year the sixth day of Pesach is Thursday night/Friday, and Purim likewise was on Thursday night/Friday.)

There are two problems with this correlation, however.

The first problem is ד"ק: the fourth day of Pesach falls on the same day of the week as Simchat Torah in the Diaspora, which is a day later than in Israel. In Israel, Simchat Torah is combined with Sh’mini Atzeret; it is only in exile, with יוֹם טוֹב שֵׁנִי שֶׁל גָּלֻיּוֹת, the extra Festival day in exile, that Simchat Torah and Sh’mini Atzeret are separated into two different days.

So the Ba’al ha-Turim’s א"ת ב"ש system is calibrated for exile, not for Israel.

The second problem is that the Ba’al ha-Turim concluded this א"ת ב"ש system with ו, the sixth day of Pesach: and he found no Festival beginning with ע, to correspond to ז, the seventh day of Pesach.

It would take some seven centuries for the tikkun (the rectification) of the Ba'al ha-Turim's list calibrated for the Land of Israel to come; but come it eventually did.

It was the Ga’on, Rabbi Amram Abu-Rabia’, affectionately known as the Netivei Am for the book by this title which he wrote in two volumes (published in 1964 and 1966), halakhic responsa with particular reference to the ancient Jerusalemite traditions, who first suggested it.

Born in Morocco in 5652 (1892) to a long line of illustrious rabbis, his family made Aliyah when he was 14, settling in Jerusalem which was at the time under Turkish Islamic occupation.

Shortly after Israel became independent in 1948, Rabbi Abu-Rabia’ completed the Ba’al ha-Turim’s א"ת ב"ש system by finding the Festival beginning with ע, which falls on the same day of the week as the seventh day of Pesach:

He noted out that in any given year, ז, the seventh day of Pesach, falls on the same day of the week as יוֹם הָעַצְמָאוּת, Israel Independence Day. So this year, for example, the seventh and final day of Pesach falls on Shabbat, and two weeks later, the 5th of Iyyar, יוֹם הָעַצְמָאוּת, Israel Independence Day will also fall on Shabbat.

The א"ת ב"ש system was completed, almost three-quarters of a millennium after the Ba’al ha-Turim had first published it, and the tikkun for the Land of Israel was at last in place: the ע for which the Ba’al ha-Turim could find no Festival, stands for עַצְמָאוּת, Independence.

And now I add my own observation of the א"ת ב"ש system:

The first and the last of these, the א (corresponding to the 9th of Av) and the ז (corresponding to Yom ha-Atzma’ut) are connected: the first was the end of our national independence, and the second was when we restored our independence (not the Holy Temple, of course). From destruction to restoration took 1,878 years – but we got there in the end.

The second and second-from-last, Shavuot and Purim, are likewise connected: though G-d gave us the Torah on Shavuot, our real acceptance of the Torah was in Shushan in Persia some 1,000 years later:

This follows the Talmud’s analysis of the phrase, “They stood at the bottom of the Mountain” (Exodus 19:17); the wording בְּתַחְתִּית הָהָר connotes “under the Mountain”, hence the inference that G-d suspended Mount Sinai above them like a vat, telling them: “If you accept the Torah – well and good; and if not – here will be your burial-place” (Shabbat 88a, Avodah Zarah 2b; also Midrash Tanchuma, Noach 3).

This suggests that at Sinai they did not accept the Torah out of pure free-will, rather out of coercion. The acceptance of Torah out of pure love and free-will happened a millennium later in the days of Mordechai and Esther, when “the Jews established and accepted upon themselves and upon their descendants, and upon all who would join them” (Esther 9:27) the entire Torah.

The third and the third-from-last, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, are obviously connected – the beginning and end of the Ten Days of Repentance.

And the middle one, Simchat Torah, stands alone, unconnected with any of the others.

Hence we can represent the relationship between the seven days of Pesach and the seven Festivals to which they correspond with a schematic diagram:

This, remarkably, is a perfect representation of the Menorah, the pure gold seven-branched Candelabrum in the Mishkan (the Tabernacle), later in the Holy Temple!

The month of Aviv (Spring), which ever since the late Biblical period we have called Nisan (see Esther 3:7, Nehemiah 2:1) is the first month of the Jewish year, and Pesach is the beginning and the basis of our national calendar.

Just as the Menorah cast its light over the Heichal, the Holy Place of the Mishkan, and later of the Holy Temple, so Pesach and indeed the entire month of Nissan spreads its light over the entire Jewish year.