In the months following the atrocities of October 7, Spain-and Barcelona in particular-has undergone a disturbing metamorphosis, one that has startled Jewish communities across Europe and reverberated through diplomatic corridors far beyond the Iberian Peninsula. A city long celebrated for its cosmopolitan openness, architectural grandeur, and cultural pluralism has found itself at the epicenter of a wave of hostility that transcends legitimate political dissent and veers unmistakably into the territory of resurgent antisemitism.

What has unfolded since that autumn day is not merely a succession of isolated incidents, but the emergence of a political and social climate in which animus toward Israel has bled, with alarming frequency, into aggression toward Jews as Jews.

The transformation has been as sudden as it has been unsettling. In Barcelona, public discourse has been increasingly suffused with rhetoric that frames Israel not as a controversial state actor but as a pariah entity to be symbolically erased, economically isolated, and culturally delegitimized. This atmosphere has not been confined to the margins. On the contrary, it has been catalyzed and amplified by official decisions taken by municipal and national authorities, decisions that have lent institutional imprimatur to sentiments that, in previous eras, might have been relegated to the fringes of protest culture.

Among the most striking of these gestures was Barcelona’s declaration of “Palestine" as its symbolic eleventh district, a move that went beyond symbolic solidarity to include the allocation of public funds to UNRWA, an organization that has been widely criticized for deep infiltration by Hamas operatives. For many in the Jewish community, the decision felt less like a humanitarian overture and more like a municipal endorsement of a narrative that blurs the line between advocacy for Palestinian Arab welfare and alignment with extremist actors. The symbolism was compounded by the city’s organization of a massive “concert for Palestine," during which Israel was erased from a projected map of the region.

At the event’s emotional crescendo, the son of Marwan Barghouti-a convicted terrorist responsible for the murder of civilians-was invited onto the stage to call for his father’s release, greeted by cheers from thousands. The spectacle, in its choreography and rhetoric, conveyed not merely criticism of Israeli policy but a valorization of figures associated with lethal violence against Jews.

Barcelona’s universities, historically bastions of intellectual inquiry and debate, have not been immune to this climate. The University of Barcelona’s launch of “Facultat 18," a project explicitly designed to raise and transfer funds to UNRWA, further entrenched the perception that academic institutions were becoming conduits for politicized activism with scant regard for the complex realities of the organizations they were endorsing.

For Jewish students and scholars, the initiative symbolized a narrowing of the discursive space in which nuanced or dissenting perspectives could be safely articulated. It also reinforced the sense that the city’s educational elite were participating in the same moral economy that had begun to dominate municipal politics.

Beyond these high-profile gestures, the everyday texture of life in Barcelona has been increasingly marred by a proliferation of antisemitic graffiti. Over the past two years, hateful slogans and imagery have appeared in hundreds of locations, transforming walls, doorways, and public squares into canvases of intimidation. The desecration of a Jewish cemetery, emboldened by the ambient rhetoric of hostility, marked a particularly chilling escalation. Cemeteries, repositories of memory and sanctity, are often the first sites targeted when hatred seeks to announce its permanence.

The smashing of headstones at the Les Corts Jewish Cemetery in January, which Israel’s Foreign Ministry linked to the broader anti-Israel campaign of Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s government, reverberated as a symbolic assault on the dignity of the dead and the security of the living.

The response from Spanish Jewish organizations was measured but unmistakably anguished. The Federation of Jewish Communities of Spain and the Jewish Community of Barcelona condemned the vandalism in the strongest possible terms, framing it as part of an ongoing wave of hostility toward Jews. While these organizations stopped short of directly attributing responsibility to the government, their statements conveyed a palpable sense of vulnerability, an acknowledgment that the social environment had deteriorated to the point where such acts could no longer be dismissed as aberrations.

The hostility has not been confined to symbolic or rhetorical domains. Concrete actions have begun to constrict the civic and economic space available to Jews and Israelis in Spain. A new royal decree “against the genocide in Gaza" led Spanish bank Sabadell to freeze bank accounts, a move that sent shockwaves through the business community and raised questions about the potential weaponization of financial institutions in service of political agendas.

Around two thousand pro-Palestinian demonstrators gathered outside the hotel housing Hapoel Jerusalem’s basketball team in Barcelona, harassing and effectively hunting the players in a display of mob intimidation that forced authorities to acknowledge their inability to guarantee safety. A Maccabi Tel Aviv game was held in the city without spectators for the same reason, a stark testament to the erosion of basic security assurances.

Perhaps most disquieting was the emergence of an anonymous online project, Barcelonaz, which published a map identifying Jewish-owned businesses across Catalonia. The creation of such a registry evokes historical precedents that Europe, in its postwar moral reckoning, had vowed never to repeat. Even if the project’s authors cloaked their motives in the language of activism, the act of singling out Jewish enterprises for public identification carries an unmistakable resonance with darker chapters of European history. The targeting of commerce, a sphere in which Jews have long been both participants and scapegoats, underscores the extent to which contemporary anti-Israel activism in Barcelona has slipped into patterns of collective stigmatization.

The climate has grown so fraught that Jewish institutions are now urging universities abroad to suspend exchange programs with Barcelona, a measure that would have been unthinkable in a city once prized as a hub of intercultural exchange. Such calls reflect a grim calculus: that engagement, in the current environment, may expose Jewish students to hostility that institutions are either unwilling or unable to confront.

The withdrawal of Spain from Eurovision to avoid sharing a stage with a Jewish artist further illustrates how cultural diplomacy itself has become entangled in the politics of exclusion.

The reverberations of Spain’s posture have not been confined to Europe. In Washington, concern has been mounting that Spain’s recent legislative measures amount to formal economic discrimination against a close American ally. In December 2025, a coalition of Republican lawmakers, led by Congresswoman Claudia Tenney, called on the U.S. Treasury Department to review Spain’s actions under Section 999 of the Internal Revenue Code, which governs American responses to foreign participation in unsanctioned international boycotts.

The letter, signed by seventeen members of Congress, reflects anxiety that Spain’s prohibition of arms trade with Israel and its ban on advertising products originating from Judea and Samaria align with the objectives of the global Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement. At stake, the lawmakers argued, is not only the U.S.-Israel relationship but the integrity of long-standing American laws designed to shield U.S. companies from being compelled to comply with foreign boycotts that Washington does not endorse.

The measures enacted by Spain in October represent a qualitative escalation beyond symbolic condemnation. By targeting arms trade and commercial advertising, Madrid has moved into the realm of concrete economic sanctions, a posture that carries implications for multinational corporations and bilateral relations alike. The legal and political status of the territories in question remains contested internationally, yet the unilateral nature of Spain’s restrictions has been interpreted by critics as a form of economic coercion that risks entangling U.S. firms in foreign policy disputes that conflict with Washington’s own positions.

Israel’s acting ambassador to Spain, Dana Erlich, has articulated these concerns with growing urgency. In an interview with Israel’s Channel 12, she accused Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s government of fueling antisemitism through its aggressive anti-Israel rhetoric and punitive policy measures. Erlich’s remarks underscore the extent to which the Gaza war has reshaped Spain’s posture toward Israel, and how that shift has, in her estimation, translated into a hostile environment for Spain’s Jewish community. She arrived in Madrid, she said, without illusions about the governing coalition’s stance, yet with a belief that dialogue remained possible. That hope, she suggested, has been repeatedly undermined by what she described as a systematic campaign to marginalize Israel on the global stage.

The Spanish government, for its part, has framed its actions as principled opposition to what it falsely characterizes as Israeli misconduct in Gaza. Yet the conflation of geopolitical critique with domestic policy measures that disproportionately affect Jewish individuals and institutions has generated a moral hazard. When state rhetoric adopts absolutist language, it can legitimize a spectrum of social behaviors that range from verbal abuse to physical vandalism. The desecration of cemeteries, the mapping of Jewish businesses, and the harassment of visiting athletes do not emerge in a vacuum; they are nourished by a public discourse that renders Jews, collectively, as proxies for a distant conflict.

Barcelona’s predicament thus raises broader questions about the responsibilities of democratic societies in an era of polarized geopolitics. Criticism of state policy, even sharp criticism, is a legitimate component of democratic debate. Yet when such criticism is articulated through symbolic erasure, cultural boycotts, and economic sanctions that disproportionately stigmatize an ethnic or religious minority, the boundary between political dissent and collective vilification becomes perilously thin.

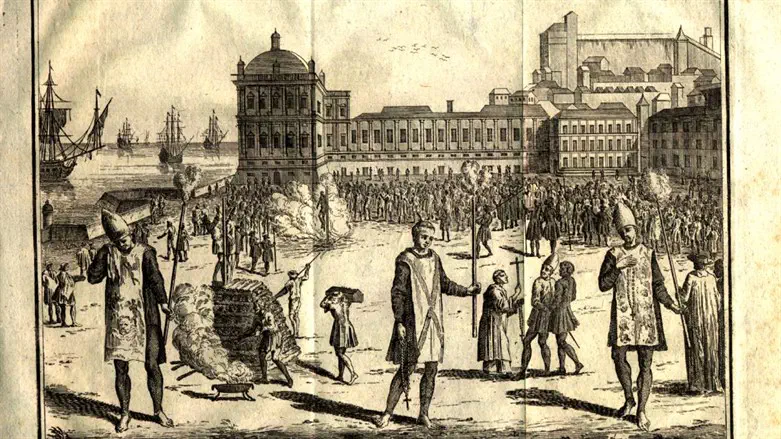

Europe’s post-Holocaust commitment to safeguarding Jewish life was predicated on the recognition that antisemitism often masquerades mendaciously as moral critique before revealing its more virulent forms.

The situation in Barcelona, with its convergence of official policy, cultural activism, and grassroots hostility, serves as a cautionary tableau. It illustrates how swiftly a city’s moral self-conception can be unsettled when global conflicts are refracted through local politics without the ballast of historical memory. The appeals by Jewish institutions to suspend academic exchanges are not merely defensive gestures; they are signals of a profound rupture in the trust that once undergirded Barcelona’s reputation as a safe haven for pluralism.

Whether Spain will recalibrate its course remains an open question. The international scrutiny prompted by Washington’s legal inquiries, the diplomatic rebukes from Jerusalem, and the quiet exodus of Jewish engagement from Catalan institutions may yet compel a reexamination of policies that have, intentionally or not, contributed to an atmosphere of exclusion.

What is clear is that the events since October 7 have left an indelible mark on Barcelona’s civic fabric. A city that once prided itself on its capacity to absorb difference now stands at a crossroads, confronted with the urgent task of disentangling legitimate political advocacy from the age-old poison of antisemitism.