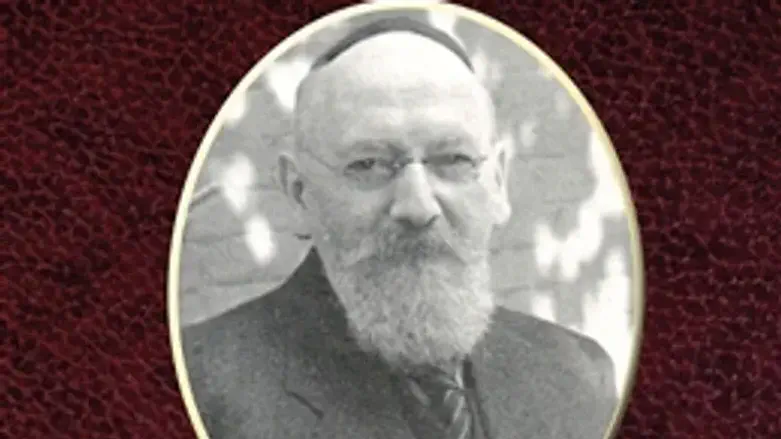

The book “Hermann Schwab, Historian of German Jewry, His Life and Shorter Works” is an unusual, worthwhile read about a prolific, G-d fearing Jewish journalist and historical writer blessed with leadership qualities and humility, a multi-talented and principled figure I would have loved to know.

The story of his early life gives us an eye-opening, nostalgic picture of the golden age of observant German Jewry living in small towns before the war, while his historical writings on Orthodox German Jewry serve as their memorial. The books he authored, A World in Ruins, The History of Orthodox Jewry in Germany, Rural Communities in Germany, and Memories of Frankfort, are the most respected works on the subject, and in addition, the many facets of his creative talents led to his writing poetry and also a book of children’s stories that was a favorite for many years and translated into eight languages.

Schwab (1879-1962) was, in his younger years, employed as clerk in a metal enterprise in Messingwerk and then advanced to a managerial level at the Aron Hirsch concern in Halberstadt. Although his real talents lay in organization and writing, his stellar qualities shone through as he filled both positions with unflinching dedication and unquestioned integrity. And that integrity is the lasting impression created by the book.

Eventually, Schwab became a journalist for the Frankfurter Zeitung, the Vossische Zeitung and other newspapers, as well as editor of the Juedischer Volksschriftenverlag. A supporter of Agudat Yisrael, established in response to the rise of Zionism, and its founder, Jacob Rosenheim, Schwab organized and raised funds for the organization’s war orphans' fund during World War I as it established several orphanages in Poland. From 1927 he ran a press service in Berlin which he continued after emigrating to England in 1934, thus escaping Hitler. In London, he became president of the Golders Green Beth Hamidrash.

While it begins with his biography, including a portrayal of his harmonious marriage, the book brings him to life in a selection of his works, sensitively translated by his granddaughter, Naomi Schwab Schendowich.

A most engaging and unusual aspect of this admirable man’s life are his beautiful and imaginative children’s stories, a sample of which are included in the book. I read three of them to my grandchildren of all ages (and their parents) at the Seuda Shlishit table one Shabbat and was gratified to see how they were all caught up in the beautiful language (thanks to the translator’s excellent work) and atmosphere. The book of stories has been unavailable for years, and I strongly suggest the translator see to its republishing in Hebrew and English.

As a child, Hermann Schwab was privileged to hear the last sermons of Rabbi Samson Rafael Hirsch zt'l, the guiding light of German Jewry and intrepid promoter of a Torah and Derech Eretz philosophy for Jewish life that met modernity without altering halakhic commitment. Schwab, who joined the school of the Israelitische Religionsgesellschaft (Adass Yeshurun) that fought Reform Jewry’s infiltration into German Orthodox Jewish life, was asked to speak at the centenary of Rabbi Hirsch’s birth, and the inspiring address he delivered in 1908 is a fascinating way to understand both the great Torah luminary he memorialized and the life of cultured but undiluted Judaism, he espoused. (Arutz Sheva brings a taste of Rabbi Hirsch’s Torah ideas every week, kindly sent by Dr. Elliot Resnick, who has published on the subject).

The book traces the rise of the Agudat Yisrael Movement through an essay Schwab penned on its founder, Jacob Rosenheim, and another engrossing essay explaining the movement’s negative attitude to Zionism, which, he explains, was caused by the overwhelming non-religious makeup of the Zionist Congress delegates.

Painfully and from the heart, in the same straightforward way in which he led his life, Hermann Schwab wrote:

“And yet we cannot but ask ourselves whether there was no way open to Orthodox Jewry in the birth hour of Zionism, but outright rejection. Perhaps they should have taken up their place behind Herzl and striven to direct his plans into the right channels with the cry ‘For a Jewish Palestine’ in place of ‘Palestine for the Jews.’ World Orthodoxy had at its disposal not only the material but the spiritual means of building up a Jewish Palestine. As it was, through a period of fifty years, Zionism separated Jews instead of drawing them together.”

“What use is it to us to build houses, if they are not filled with Jewish life, to till fields and plant vineyards, if they and their yield will not be sanctified through the words of G-d’s teaching?”

Schwab recognizes the positive results engendered by the Zionist movement, writing: “‘Jew’ has been made acceptable again in polite society….the young people have refrained from baptism…” but that is not enough.

He writes that he cannot support a Jewish state that is not expressly founded on Jewish values. He saw the fledgling Mizrachi movement which joined the secular representatives as an insignificant drop in the bucket, which was not far from the truth at the time. Sadly, he did not live to see how significant a force it is now, one which influences the state to a great, if not satisfying, degree.

Reading his words led me to wonder if his independent and sincere way of thinking would have led him to identify with the Religious Zionists who eventually built communities, yeshivas and nationwide religious institutions (hesder, national service, etc.). Perhaps he would feel at home with the stringently observant Bnai Torah of that sector, and with the many who idealistically laid their lives on the line for the Jewish State and the Jewish People in the current war - and in such tragic numbers (20% of the population but 40% of the fallen). There is no way, of course, to know.

Ironically, there is a genre of old Jewish jokes about the German Jews, the “yekkes” (as they were called because they wore suit jackets), that poke gentle fun, somewhat enviously, at the group’s proverbial straightlaced integrity, exactitude, punctuality and unfailing decorum. None of these half-affectionate half-mocking jokes seem humorous after the Holocaust, but since Israel’s fifth wave of aliya (1929-1939) included about 60,000 German Jews who escaped Nazi persecution, the jokes continued to live on for several decades.

Not so the people whose cultural and behavioral norms they intended to portray. Those who did not leave Germany were wiped out, their wealth appropriated for the most part. And while their descendants carry on some of their customs, there are painfully few people left who can represent the unique phenomenon of the Orthodox Jews of Germany, and almost none of the ethnic groups among the myriad ingathered exiles understand the spiritual, intellectual and upstanding life these Jews embodied.

Those who do may have davened (as I did) at the Khal Adath Yeshurun (“Breuer’s”) Congregation in Washington Heights, New York, built by Jews who escaped Frankfurt after Kristallnacht, with its special liturgy, customs and melodies. (There may be similar synagogues in parts of Europe or Israel with which I am unfamiliar). The Horev complex of schools in Jerusalem was founded by Orthodox German Jews a century ago, but although Torah-true and academically superb, there is barely a trace of the unique Orthodox German world among its teaching staff and students today.

What a contrast those “yekkes” are to today’s Israeli political morass. What integrity they showed in their dedication to the positions they held in management, finances, mercantile and any other endeavors! The book brings all that to life in its portrayal of this respected historian, journalist, and public servant, leaving the reader full of admiration for a man of accomplishment whose sterling character and selflessness are a model to follow. Hermann Schwab was not naïve, he knew how the world worked, but he was able to get things done without compromising his values.

There are no coincidences, as many Israelis like to point out.

I read this book several months ago, reviewed it and waited for a suitable time to post it. Now that the past few days have shaken so many Israelis to the core, it seems the right time to remind ourselves that integrity is what we should be able to expect from every level of public servant.

Life is wonderful in the Jewish State, but we worry constantly and for valid reasons. We lose sleep over the wishful thinking in Trump’s plan, worry whether his judgment is clouded by his business connections with Qatar (and those of his closest negotiators), read about the rearming of Iran, the intransigence of Hezbollah, the insane hatred of the anti-Israel mobs and the corrupt UN - enemies, hatred, irrationality, antisemitism is our lot. We are concerned about where NYC (and the Western world) is going.

There is also the endless 24-hour-a-day worry over our children, grandchildren, friends’ husbands and children in the IDF, juxtaposed with the question of how to convince the Haredi community to take part in the physical defense of the country in which they live. And the best answer to all of the above and more is hope and "savlanut", patience, accompanied by the fervent belief that “Am Yisrael Chai” and that the G-d of Israel is with us. Since the Swords of Iron War began, we have seen miracles that rival the Splitting of the Red Sea and they give us strength.

But the current situation is different.

The ordinary, law-abiding Zionist Israeli citizen wavers between fury, resignation, disgust and cynicism regarding a totally different kind of issue, the betrayal of his soldier sons - those who put their lives on the line - from within the IDF. He is reeling as he learns of betrayal in the army’s judicial system, the alleged treason of the just-fired military advocate general and who knows how many other members of the Deep State who may have cooperated with her.

Traitors from within the system. Incomprehensible. Everyone in Israel saw and read of the unnecessary humiliation to which the courageous soldiers guarding Nukhba terrorists at the Sde Teman base were subjected when they were falsely accused of abusing a Nukhba prisoner - a terrorist who was taken at his word. And a video clip, later proven to be spliced and edited, allegedly showed the abuse.

Somehow, that video was leaked, and led to an immense rise in antisemitism, although it actually did not show what it purported to reveal. For months, people asked why they had not been told who leaked the video to the media. And now they know. And they also know how that fact was kept from public knowledge.

Fury, resignation, disgust and cynicism, all are part of the mainstream public's reaction to the disgrace. And as if to destroy any vestige of trust in the country's insitutions, those revelations were followed shortly after by the breaking of a huge corruption scandal involving the Histadrut Labor Union and municipal and local authorities.

This not to say that there are no trustworthy public servants in Israel, but the country is in desperate need of many more dedicated and honest Hermann Schwabs - in the role of statesmen, public servants, peoples’ representatives, straight-as-a-die judges and prosecutors. May we merit to see them emerge as our leaders in the fulfillment of Isaiah’s words: “Zion will be redeemed by justice.” Hermann Schwab would then be proud.

Rochel Sylvetsky is Senior Consultant, Op-ed & Judaism Editor at Arutz Sheva and a member of the boards of the Knesset Channel and Orot Yisrael College, formerly Chairperson of Emunah Israel and a member of Israel Education Ministry's Religious Education Council. She lives in Jerusalem.