Many historical books have been published about the world’s dictators that try to capture the events during their rule. However, writing a book and conducting research about a dictator who is still alive and exercising power is far more difficult. One reason is the fear of open and covert reactions from intelligence apparatuses loyal to the dictator, who often resort to character assassination or even physical assassination.

In the Middle East, historical research into religious despotism is especially fraught with difficulty and described as controversial because it is labeled “religious sedition” or “mafia-like religious insurrection.” For example, when Ahmad Kasravi wrote that “the Mahdi, (Imam Zaman), is a fabrication of the Shia clergy,” the assassins from the terrorist group Fada'iyan-e Islam, or Khomeini supporters linked to the Muslim Brotherhood, simply killed him. The grotesque irony is that a follower of that same murderer, Navvab Safavi, has been “Tehran’s Dictator” for thirty-seven years.

In the Middle East it is rare for researchers to investigate crimes committed by Islamic caliphates through history, because the label “Islamic” makes the task exponentially more dangerous. During Khomeini’s upheaval in Tehran and the departure of the late Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, supporters of Mosadegh tried to portray a sinister Shia cleric like Khomeini as a holy, religious icon. The BBC and the New York Times published pieces comparing Khomeini’s regime to a five-year reign of justice under Ali (interviews with Mehdi Bazargan and Bani Sadr, 1979). But the reality was different, and that fraudulent idolization has become a scourge for the Iranian people today.

If a historian dared to ask and write, “Which Ali? Based on what historical documents or evidence?” tens of terrorist groups across the Shia crescent in the Middle East would mobilize for his physical elimination.

When examining events under despotism from a historical perspective, many angles must be considered. If the despot’s rule is cloaked in religion and, under that banner, the regime uses a repression machine and a 24/7 propaganda apparatus to control a traumatized society, the historian’s work becomes even harder. How is he to proceed with a critical, analytical mindset while writing the book?

With the arrival of the internet and satellite television, two groups within Iranian society alongside the regime’s propaganda machine attempted to control public opinion: the Islamic left (the reformists) and the Marxist left (those who lost the power struggle with Khomeini). Both branches have tried to brainwash the public; most of their writings resemble party leaflets plastered on walls, using the same tricks of file-building, lying, and rumormongering against their opponents.

But the internet, satellite TV, and social networks inevitably had a striking impact on raising public awareness in Iran as well, and especially among the new generation, an actual “information explosion” occurred.

The sensitivity of the Ministry of Intelligence, the Basij, and the Revolutionary Guard reached a point where they could not tolerate any photo or content opposing the regime’s propaganda. They responded with threats and thousands of legal cases in Islamic courts. Their aggressive, repressive reactions were driven by fear of this rising awareness; they resorted largely to filtering and censorship. In such an environment, the survival of a dictatorial regime, even by cultivating superstition and presenting a fake sanctified image of the ruler becomes extremely difficult, if not impossible.

Political forces around Iran’s power circle, seeking financial and political positions, not only failed to help educate society but actively assisted in the continuation of what impedes the country’s growth: the religious dictator himself. The regime’s propaganda and repression machine, at the dictator’s instruction, even formed lobbying networks abroad and infiltrated Persian-language media outside Iran.

Consequently, Iranian society found itself trapped between the “prison of delusions” and living under the suffocating “bars of the dictator.” The entangled media and propaganda mafia of the Islamic Republic inside and outside the country have aimed to scatter and confuse the public mind, to prevent Iranian society from focusing on removing “Tehran’s Dictator” and pursuing regime change. It is no exaggeration to say that, until now, the balance has favored the regime.

A historian working in this climate faces not only media blackouts and censorship at home and abroad but also risks physical and reputational assassination by entities loyal to the “Tehran’s Dictator.” Theocratic despotism, modeled on Shia clerical rule the so-called velayat-e faqih, harbors a narrow, monopolistic mindset that considers itself divinely entitled, striving for a single permitted voice while denying the public the right to knowledge.

Like an orchestra, the regime’s foreign lobbies, media operatives, and political actors, Marxist-Islamist performers before the cameras, sacrifice themselves to execute the caliph’s or the “Tehran’s Dictator’s” directives.

Growing critical thought in such a toxic swamp is extremely difficult. The confused, collaborator mentality of the dictator rings like a bell around the neck of society. Even the mildest internal criticism, when judged by revolutionary courts, can mean death or, through the regime’s media mobs, amount to a campaign of character assassination.

Naturally, a historian writing a book against “Tehran’s Dictator” cannot escape the instruments of power. The Dictator's government is one of blood and booted military men, with a repressive, absolutist mentality and a deceitful, superstitious religiosity. Such a government will do anything - suppression, media blackout, killing intellectuals and writers, censorship, creating crises and tensions - to preserve the ruler’s fake sanctified image.

Researching and writing about a dictator like Ali Khamenei is extremely difficult especially in a society whose civil institutions are weak, whose dominant intellectual current among its thinkers is Marxist-Islamist, and where independent patriotic intellectuals can be counted on one hand. In the Third World, the media and intellectual milieu tend to be Third World as well, and manifestations of modernity are rare.

Historical research about a discredited, unpopular, chaotic, delusional, repressive ruler hidden in darkness, like Ali Khamenei, with a record of thirty-seven years of crimes, brings the author face to face with a gamble of life and death.

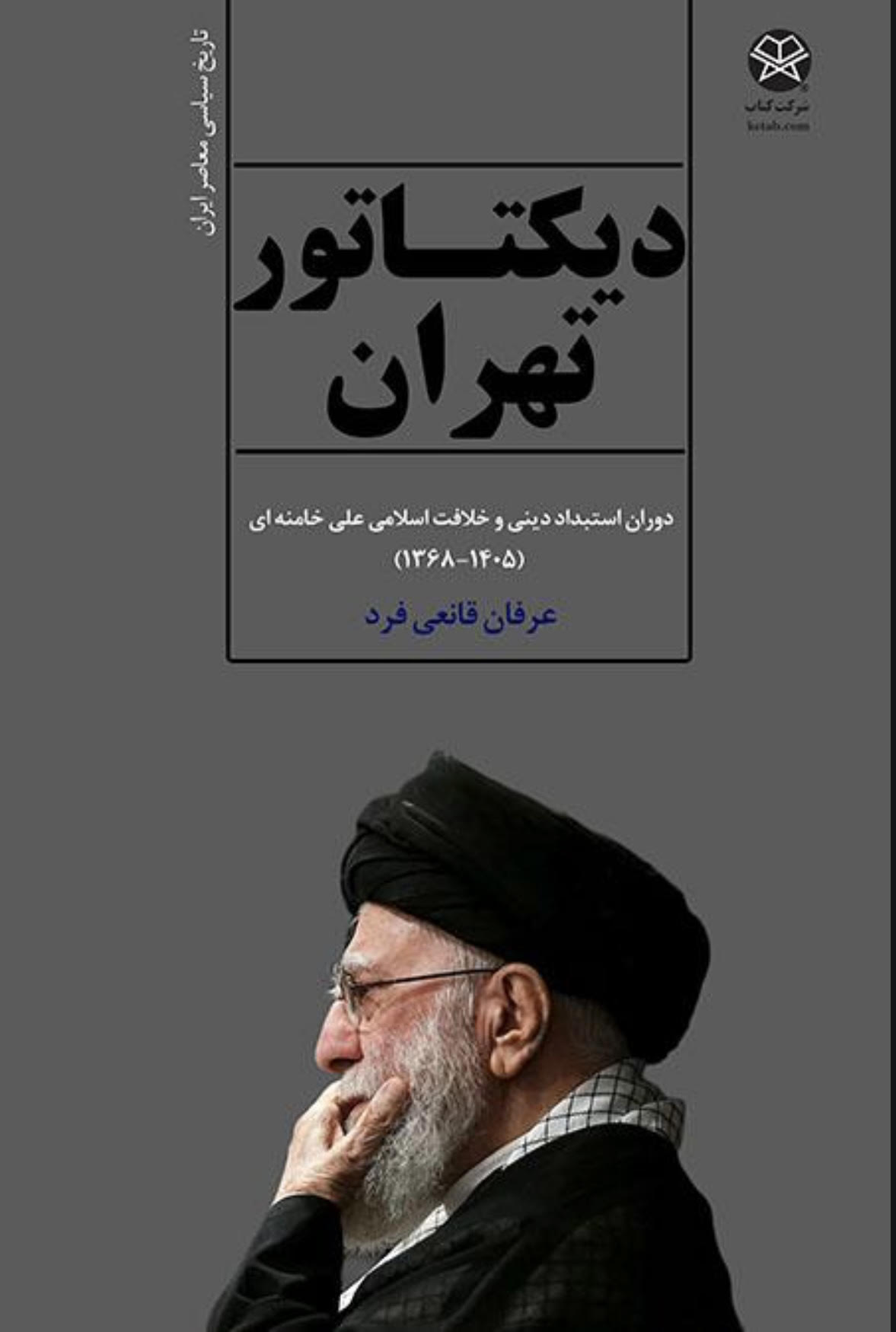

Yet today, by publishing "Tehran’s Dictator" in English, Arabic, and Persian, and by addressing only a few incidents from his era, my aim has been to give readers in every language borrowing the words of Hafez “a hundred kinds of reflection in the mirror.” Whether I have succeeded, I do not know. But I am glad that, beyond the watchful eyes of Marxist-Islamists working in the regime’s censorship and propaganda apparatus, I have published this book in America to expose the profile of the criminal dictator Ali Khamenei.

For thirty-seven years he has called himself God in the guise of Islam, killed, tortured, and imprisoned all opponents; yet I spent six years trying to show in one book that he is an opium-addicted, permanently stupefied ruler whose stupor destroyed Iran.

Certainly, after me, other writers will produce far better and more comprehensive books about Ali Khamenei.

Erfan Fard is an Iranian writer and political analyst who often writes op-eds for Arutz Sheva and currently resides in the United States. He was imprisoned by ICE for unintended immigration irregularities but his case is up for review, as deporting him is a death sentence.