At four o’clock in the afternoon of Tishah B’Av 1979, the shul of the Maimonides School in Brookline, Massachusetts, was still packed to capacity. Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, the Rav, had just concluded an eight-hour tour de force that began promptly at 8 a.m., dissecting every stanza of the kinot with equal parts halakhic rigor and literary sensitivity.

The famously enigmatic Hebrew kinot of Eleazar HaKalir and the other medieval paytanim seemed to shed their obscurity and vivid images of hurban and pogroms came alive. There was a quiet magic in the Rav’s concluding rendition of Eli Tziyon: his soft yet resolute voice braided nostalgia, searing loss, and stubborn hope into a single, unforgettable melody—one that still echoes in my mind today.

A relative of the Ḥazon Ish—temporarily in Boston for medical treatment—turned to me and exclaimed, half in wonder and half in reverence, “Learning like this on Tishah Be’Av!” A few rows away, a contingent of New Yorkers, who had left Manhattan at four that morning, gathered their belongings for the four-hour drive home; yet even as they stood, they lingered, reluctant to exit the room where lamentation had been transmuted into an encounter with living Jewish history and learning.

Seated just to my right, only a few feet from the Ark, Rabbi Isaiah Wohlgemuth—once the youngest rabbi ordained in pre-war Germany and miraculously spared from its impending catastrophe—rose to his feet, scanning the gathered throng, all poised to daven the afternoon Mincha. Nearly eight centuries earlier, in the wake of the 1096 Rhineland massacres that ravaged the Jewish communities of Speyer, Mainz, and Worms, Rabbi Meir Ben Yehiel composed the kina Haḥarishu Mimeni va-adabera (“Silence yourselves that I may speak”).

Lamenting the shattered kehillot, he pleads:

“Mourn the pious and the righteous who sank in the seething waters…

Torah, gird yourself in sackcloth and wail like an only child

for those who grasped your oars and cast your nets—

your sailors and helmsmen adrift upon the mighty seas.”

The Babylonian Talmud recounts a band of sailors who disembark upon what they assume is a tranquil island. They unpack provisions, kindle a cook-fire, and settle in—until the ground itself begins to tremble. Their “island” turns out to be the living back of a colossal fish; startled by the heat, the creature rolls, and the sailors barely scramble aboard their ship before the sea engulfs them.

In Yemei Zikkaron, the Rav reads this illusory island as the seductive stability Jews sometimes find in host societies—a temptation to treat a temporary perch as a permanent home.

The parable’s warning remains no less urgent today.

_____________________________________________________________

On a humid August night in 1943 a column of Palmach recruits left Kibbutz Eilon and trudged toward the beach of Achziv. Rumors of Warsaw in flames and trains bound for Auschwitz traveled with them; food was scarce, and British patrol boats prowled the coast. During a brief pause, the twenty‑year‑old poet Natan Yonatan, borrowing a Russian tune his friend Dan Ben‑Asher kept humming, jotted eight hurried lines in a field notebook:

A skiff is traveling, its twin sails wide;

yet all its sailors sleep inside.

A night breeze ripples the moon-lit foam;

a child keeps pacing the silent loam.

This melodic poem, popularized by the celebrated Israeli singer Arik Einstein, captures the Yishuv’s deepest anxiety: a fragile vessel adrift while its guardians doze. In later reflections, Yonatan identified the twin sails with a double mandate: one stands for the practical work of survival—food, defense, infrastructure; the other for moral and cultural direction—education, memory, mutual responsibility. The boat keeps its course only when both sails draw wind; if either fails, the skiff spins or stalls.

The poem next turns its gaze to the small, tear-filled boy scanning the shoreline for the drifting skiff.

Small is the boy, sorrow fills his eyes;

the water rolls toward unmeasured skies…

If none of the sailors wakens soon,

how will the skiff reach harbor and dune?

“Dugit Nosaʿat” thus endures not merely as wartime nostalgia but as a portable ethics of attention. It reminds successive generations that storms can rise faster than resolve, and that the simplest act—opening one’s eyes—may mark the difference between drifting aimlessly and steering toward land and a promising future.

This reminder remains no less urgent today.

________________________________________________________________

When asked whether Jews of the Second Temple period commemorated Tishah BeʾAv in mourning for the First Temple, the Rav replied that they did, explaining that “the specter of ḥurban—destruction—continued to haunt the land.

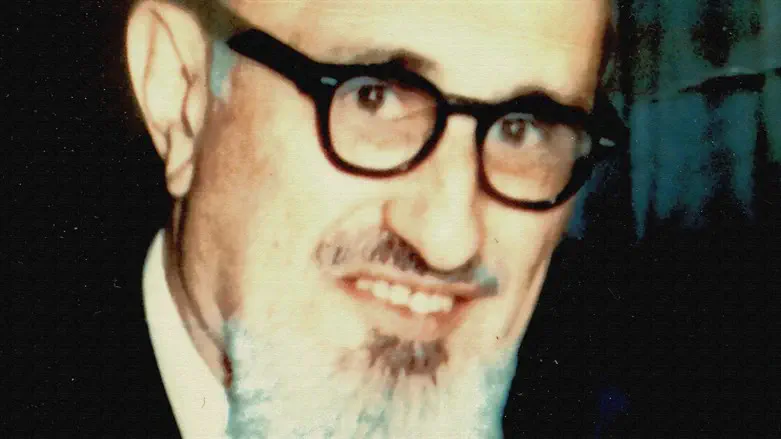

Itzhak David Goldberg MD, FACR is Professor Emeritus at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and was a student of Rav Soloveitchik zts"l.