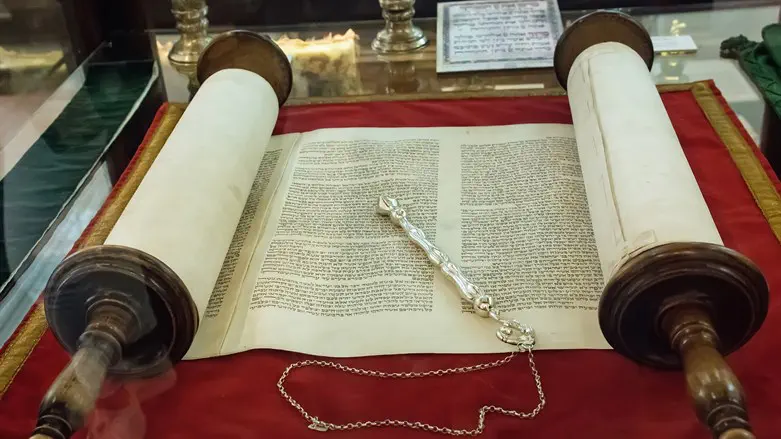

The Torah's Vision of Justice and Human Dignity

This past Shabbat's Parsha, Mishpatim, sets out the ordinances by which Jewish society is to be governed. The ideal state envisioned by the Torah is one based on the principle of justice in every area of human endeavor. According to the Torah, all people were created in the Image of G-d and, therefore, may not be mistreated in any way.

In fact, the entire notion of human dignity is rooted in the Torah’s account of Creation. From there, it is clear that G-d does not favor any race, as all mankind evolved from a single individual named Adam, who was not assigned any particular color or racial composition. The notions of race, color, and other dividing factors came into being later and were a human invention. The Torah proclaims regarding every human being: “G-d created man in His Image; in the Image of G-d He created him; male and female He created them” (Bereishit 1:27).

This foundational idea inspired America’s Declaration of Independence, which states, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights...” There is no doubt in my mind that America’s unparalleled success as a society and its transformation from a small federation of thirteen colonies into the most powerful and advanced nation on earth is closely related to its dedication to the freedom and dignity of all people.

Beyond Prevention: The Ideal of Humanitarian Responsibility

A major purpose of the Torah is to curb reckless social behavior and to make individuals responsible for the damages they cause through negligence. However, the Torah’s intention is not limited to prevention. It is not enough for a Jew to simply refrain from harming his neighbor. He must live according to the credo of “You shall love your friend as yourself” (VaYikra 19:18). This implies a humanitarian activism obligating him, among other things, to provide assistance and care for his “friend” and his friend’s property. The obligation to assume responsibility for another’s lost object—even animals—and to ensure they are returned to their rightful owner represents a very lofty ideal.

The Torah’s moral expectations, however, extend even further. Surprisingly, the command to act magnanimously is not limited exclusively to one’s friends or neutral acquaintances. The Torah, quite surprisingly, states: “If you encounter the ox of your enemy or his donkey wandering, you shall surely return it to him. If you see the donkey of someone you hate crouching under its burden, would you refrain from helping him? You shall surely help him” (Shemot 23:4–5).

The Challenge of Helping an Enemy

(Note: This does not refer to a mortal enemy like Amalek and Hamas.)

At first glance, this seems contrary to ordinary moral sensibilities. Most decent individuals believe it is reasonable to treat others as they treat you. If someone is kind, you respond with kindness; if someone is mean-spirited, you are not obligated to assist him in his time of need. Why should we go out of our way to help someone who acts contemptibly? Wouldn’t it be more appropriate to leave him to his own devices so that he might learn a lesson—that if you wish to benefit from others’ generosity, you must also be willing to help others in return?

In my opinion, the Torah does not want us to judge people based on how we feel about them. Our natural tendency is to regard those who treat us well as good, decent individuals, while those who dislike us or act negatively toward us, we instinctively dislike and label as bad people. But is this the correct approach? The Torah commands: “Do not hate your brother in your heart” (Vayikra 19:17). Even if someone has wronged you, you must not vilify him; rather, you should strive to redress the grievance calmly and rationally and uproot any contempt from your heart.

We must remember that, from an objective standpoint, every Jew is a member of the Jewish people and is therefore entitled to our respect. He must be regarded as a member of our family, who should not be summarily discarded because of unseemly behavior. The Torah’s goal is always the restoration of even damaged relationships, if possible. We are commanded to come to another’s assistance because of his objective status as a member of the Jewish people—not because of how we feel about him.

The Rambam applies this law even to one who openly violates the Torah and refuses to change his ways despite rebuke. Such a person, we are commanded to “hate.” Yet, even in this case, when his animal is struggling under its load, and he desperately needs help, we are not permitted to abandon him. May we leave him alone in an unsafe place because of his sins? Absolutely not.

Transforming Personal Feelings into Objective Morality

Interestingly, when Moshe repeats this law in the Book of Devarim, he frames it differently: “You shall not see the donkey of your friend or his ox fallen on the road and ignore them; rather, you shall lift them up with him” (Devarim 22:4). Moshe changes the word “enemy” to “friend.” Did he mean to say that we should only help friends, not enemies? Absolutely not! Rather, Moshe’s emendation is intended to teach us an important lesson.

There may be individuals whom we dislike for very good reasons. They may not be worthy of our friendship or assistance. However, we should treat them as we would members of our family—not because they deserve it, but because we don’t want to see them exposed to danger and suffer unnecessarily or even die. We want them to live, rectify their flaws, and ultimately become our friends once again. Moshe changes the designation from “enemy” to “friend” because if we treat even our estranged brethren as true friends, we pave the way for genuine Teshuva (repentance) and reconciliation.

The holiness of the Jewish people lies in their refusal to live by the morality of personal feelings. Instead, we are commanded to “negate our will before His Will” (Avot 2:4). As the Creator declares: “It is not My desire that the wicked shall die, but that the wicked turn from their [evil] ways and live” (Yechezkel 33:11). Our goal is to emulate, as best we can, the “Ways” of our Creator. This is the path toward both personal and societal perfection.

May Hashem assist us in our endeavors to achieve this.

abbi Reuven Mann has been a pulpit Rabbi and a teacher of Torah for over fifty years. He is currently the Dean of Masoret Institute of Judaic Studies for Women and resides in Arnona, Jerusalem.

Questions? Comments? Please reach out

to Rabbi Mann on WhatsApp 050-709-2372 or by email at: rebmann21@aol.com