Newly uncovered documentation appears to confirm that Catholic convents and monasteries sheltered more than 3,000 Jews from the Holocaust following the Nazi takeover of Rome in 1943.

The papers, which have yet to be made public, were discovered at Vatican City’s Pontifical Biblical Institute and announced on Thursday. They contain the names of 3,200 people who have been verified to be Jews by the organizing body of Rome’s Jewish community.

The research was a joint project of the institute, Rome’s Jewish community, and Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust museum, in addition to two Catholic-affiliated universities. It was coordinated by Dominik Markl, a scholar at the institute.

The discovery appears to further complicate the already ambiguous narrative surrounding the Catholic Church and the Holocaust. For decades, historians have battled over how to interpret the actions of Pope Pius XII, who signed a treaty with Nazi Germany as a Vatican official before he ascended to the papacy. Later, he maintained a public silence as thousands of Italy’s Jews were rounded up and deported to concentration camps, where nearly all of them perished.

Much of the postwar scholarship, including work drawing on recently unsealed Vatican archives, has argued that Pius XII was indifferent to the fate of the Jews. But some researchers favorable to the church have long maintained that, behind the scenes, it was working to save as many Jews as possible through back channels.

“The documentation thus significantly increases the information on the history of the rescue of Jews in the context of the Catholic institutions of Rome,” the three partner organizations said in a joint statement announcing the findings.

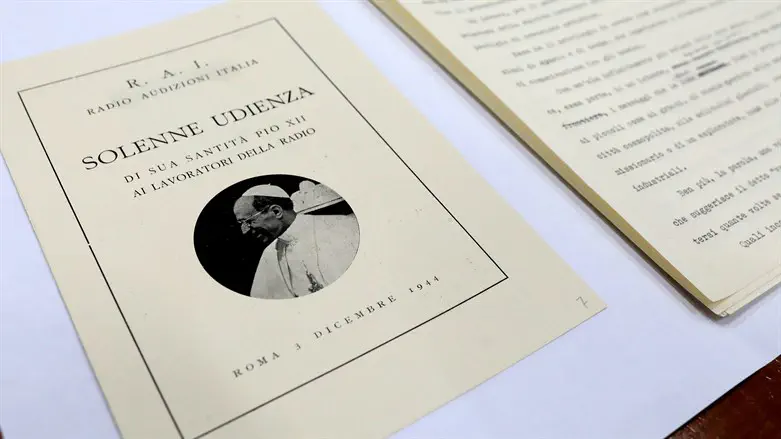

The documents, which were thought to have been lost, confirm that Catholic institutions did save thousands of Jews as others were deported from Rome’s Jewish Ghetto, across the Tiber River from the Vatican. Compiled between 1944 and 1945 by Father Gossolino Birolo, an Italian Jesuit priest, the papers list the names of around 3,600 people sheltered by more than 150 Catholic religious institutions. Previous documentation said that Catholic institutions had hidden thousands of people, but had not listed their names.

But some scholars are cautioning against drawing too many conclusions about the church from the document, which was compiled between the Allied liberation of Rome in 1944 and 1945, according to the Vatican. The list has not yet been made publicly available to historians, leading David Kertzer, a Pulitzer Prize-winning Jewish historian of the Vatican who has published two books on its actions during World War II, to express skepticism regarding its contents.

“I hopefully will be allowed access to this document, as there is much about it that remains unclear from the press release and the press reports to date,” Kertzer told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in an email. “As most of the people finding refuge in Rome’s religious institutions during the German occupation of the city were not Jews, I wonder how and why the list would have been compiled in 1945.”

Kertzer also noted that many Catholic institutions would only take in Jews who had been baptized and were considered Catholic.

“We may see this document used to revive and bolster what we might call redemptive narratives about the ‘good’ Catholics who saved thousands of Jews,” Robert Ventresca, interim academic dean of King’s University College in Ontario who specializes in Pius XII research, told the Jesuit publication America. But, Ventresca cautioned, “There is a more complex reality at play even in the case of so-called ‘rescue’ during the Holocaust.”

The Vatican, which last year hosted the director of Yad Vashem for the first time, has been active on other fronts when it comes to Holocaust remembrance. This weekend the church will beatify a Polish family murdered by the Nazis in 1944 for sheltering Jews, bringing the family one step closer to sainthood. Italy’s far-right government also announced earlier this year that it would build a new Holocaust museum in Rome.