The Talmud tells us that he who saves the life of one Jew can be thought of as having saved an entire world. Other editions of the Talmud state that saving the life of any human being, Jew and non-Jew alike, is comparable to saving an entire world.

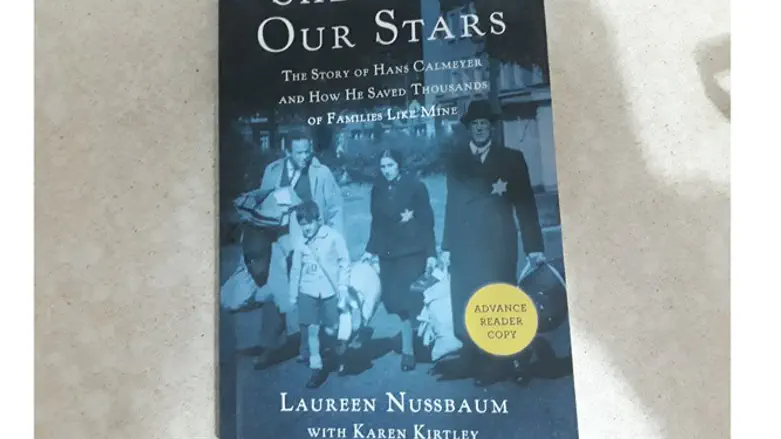

What would those Sages say about someone who, during the darkness of the Nazi era, saved the lives of thousands of intermarried Jews and non-Jews and their families, by finding a way to list them all as bona fide non-Jews – doing this with steadfast determination, despite the considerable risk to his own life? Unbelievably, the fascinating story of the man who did just that remained unknown until this year, when the book Shedding our Stars, the Story of Hans Calmeyer and How He Saved Thousands of Families Like Mine (She Writes Press, 2019) by Laureen Nussbaum, was published - decades after his death.

The year is 1940. Hans Calmeyer, a secretly anti-Nazi German lawyer with humane beliefs, is drafted to an SS unit but opts to join an organization taken over by the Luftwaffe whose specialty is foreign airplane sightings. He volunteers to serve near the Dutch border and when the Dutch army surrenders in May, the reluctant soldier's unit moves to Rotterdam.

In December, he interviews for a position in the Reich's Interior Ministry which soon issues a decree defining what constitutes a "Jew" and which requires all Jews in the Netherlands to report to the authorities. Rival factions in the Nazi party interpret the German racial law differently and Calmeyer is charged with interpreting it in the Netherlands so as to settle doubts about the Jewishness of those on the Dutch list.

Calmeyer uses his considerable and respected legal talents to argue persuasively against article 3 of the decree. His opinion is accepted and that clause, stating that a grandparent was racially Jewish if he or she was a member of a Jewish congregation, is opened to refutation by individuals whose race is in doubt. This opens the door for petitioners to claim that they are not in fact Jewish and for decisions of doubtful ancestry to be made for over 5600 cases. Calmeyer has brilliantly shifted the emphasis to proving an undocumented forebear was Jewish instead of forcing the petitioner to prove that this forebear was Aryan, and that makes all the difference. Thanks to his legal expertise, murderous German pedantry is bested using its own meticulous methods.

Appointed the Reichskomissar in the Netherlands, Calmeyer is then officially assigned the authority to decide on questionable cases with regard to the Reich's definition of Jew. He is given considerable autonomy and thus holds the life or death of thousands in his hands - and he uses his power bravely and well.

What gave him the courage to research, then falsify, destroy and alter family records when he felt it was possible to save people? It was a combination of abhorrence for Nazi ideology, his own ordinary human decency and the firm belief that the way to fight the evil that had found root in his native land was to do whatever he could to prevent the wanton genocide of Jews. He did this with two loyal co-workers and without public heroics, without joining the partisans, without fanfare and without talking about it, managing to thwart Nazi inspections and criticism. Bringing attention to himself in any way would not only have gotten him killed, it would have stopped his efforts, he later wrote.

Good men were scarce in the Nazi machine during the Holocaust. Good men who took risks to save Jews were rare indeed. In the Netherlands, where 90% of the Jewish population did not survive Nazi genocide, many due to Dutch neighbors' turning them in or reporting their hideaways (as in the case of Anne Frank), his daring is even more laudable, taking on even more significance.

It is riveting to read Calmeyer's story through the eyes of the book's author, then the school-age daughter of one of the families he saved. Her father was Jewish, her mother a non-Jew, and Calmeyer used her non-Jewish grandmother's alleged relations with another non-Jew to classify her and her siblings as non-Jewish and her mother's marriage to a Jew a "privileged intermarriage." This enabled mother and children to "shed their stars," – giving rise to the book's name - escape being sent to the camps and to survive the hardships of the war as part of the civilian Dutch population instead of being slated for extermination. The writer's vivid description of life during the frightening period when her family was considered Jewish contrasts starkly with how she was able to live once the hated yellow star was removed and makes Jewish suffering all the more horrifying, the Nazis' relentless lust for murdering Jews and anyone with a Jewish bloodline all the more abhorrent.

Laureen, then called,Hannelore, was friendly with Anna and Margot Frank and describes their sudden disappearance as well as what befell other Jewish families, including her future husband Rudi's parents who died in the camps and the suicides of Jewish neighbors who had escaped to the Netherlands and could not face falling into Nazi hands. The story of how Rudi himself cleverly escaped being caught by the Nazis is a spellbinding part of the book.

Hans Calmeyer saved thousands of lives, but in order to do so, had to reject those whose records he could not change without giving himself away and jeopardizing the entire operation. His concerted effort to remain clandestine allowed him to save many more than the number of Jews on Schindler's list, but did not lead to his starring in a movie by Steven Spielberg. Instead, he was actually imprisoned after the war, denounced as part of the Nazi genocide machine by a woman whose family came to him but was rejected because he could not find a way to alter their records. Those whom he was able to save, however, came forward and served as living proof of the thousands he removed from Nazi clutches. Today, he is listed as a Righteous Man Among the Nations in Israel's Holocaust Museum, Yad Vashem, a title reserved for those few who courageously saved Jews.

Calmeyer suffered greatly as a result of the choices he had to make, calling his efforts "too little, too little" and torturing himself throughout the rest of his life with the thought that he might have done more. The reader, however, is filled with awe and admiration for this outwardly unremarkable Aryan lawyer and cannot help thinking how many lives could have been saved had there been another hundred Calmeyers among the bureaucrats faithfully running the genocide system. The contrast with Adolf Eichmann's claim that he was only "following orders" comes unbidden to mind...

Calmeyer's damning description of post-war Germany is as enlightening as his war time experience and goes a long way towards explaining the despicable rise of antisemitism today in the country that once blindly followed Hitler. Writing soon after the war, he is shocked to see the same Nazi bureaucrats continuing to run his native land, unashamed, unrepentant, and ubiquitous – realizing that he was but a drop in the bucket filled with willing, believing Nazis. It seems, he reveals, that the allies only got to the leading figures in the Third Reich, and that the ordinary, plodding Nazi bureaucrats were whitewashed, with all guilt swept under the carpet, allowing them to remain in place. The old elites, the big banks and industrial giants who helped the Nazis and whose liquidation had been recommended by investigators, were left untouched.

Famed writer Alfred Doblin wrote: "Here lives unchanged a hard working people of orderly habits. As always, they have been obedient to a government, latterly to Hitler, and they do not understand why this time, being obedient should have been wrong." Author and journalist William Shirer was clearer: "They do not have any guilt feelings and regret only that they have been beaten…they are sorry for themselves and not for all the people they have murdered and tortured." Adenauer was unrepentantly laconic, saying that there was no one else to help run the country. The reader realizes that it is continuity, not regression, that explains why so many of their offspring are Jew haters whose anti-Semitism is what they have in common with the Muslim migrants Angela Merkel mistakenly thought would expiate her country's wholehearted attempt to eradicate its loyal Jewish minority during the Hitler years..

Hans Calmeyer deserved to have his important story told. It is evident that much research and efforts went into its writing and that the book's 92 year old author is able to look at the world, after decades of personal accomplishment, with the wisdom of experience. She says in an interview that the situation in the world shows many parallels with that of the Weimar Republic that allowed Hitler to rise to power and hopes that it is not too late to draw lessons from history.

The only part of the book I found somewhat less interesting was the writer's detailed description of her own family's life long after the war, added at the advice of friends who thought it would provide human interest to the book. It is somewhat jarring when she tells of her family's move to America and affiliation with the pacifist Quakers. She does not mention or perhaps does not know, that they are also avowed antisemites.

On the one hand, her Jewish survivor husband's illustrious scientific career serves to emphasize, by contrast, how many other brilliant minds were lost at Auschwitz. On the other hand, the couple's view of life that embraces pacifism as if there is no evil in the world that must be fought once the Nazis were defeated, is not particularly realistic. In that vein, this reviewer feels that Nussbaum's sympathy for the German girls her age who suffered during the allied bombings towards the war's end is misplaced. We would all have wished that only Nazi ideologues be the ones to pay for their sins, but bombing Dresden, for example, saved untold lives because it was the center of Nazi industry and most of the girls for whom she feels sorry were compliant and cooperative Nazis. Those very same Talmudic Sages quoted above, by the way, said that he who has mercy on the cruel will end up causing cruelty to be wreaked on the weak.

Hans Calmeyer was not bothered by those considerations. He quietly saved whomever he could and his story makes for a highly recommended and powerful read.