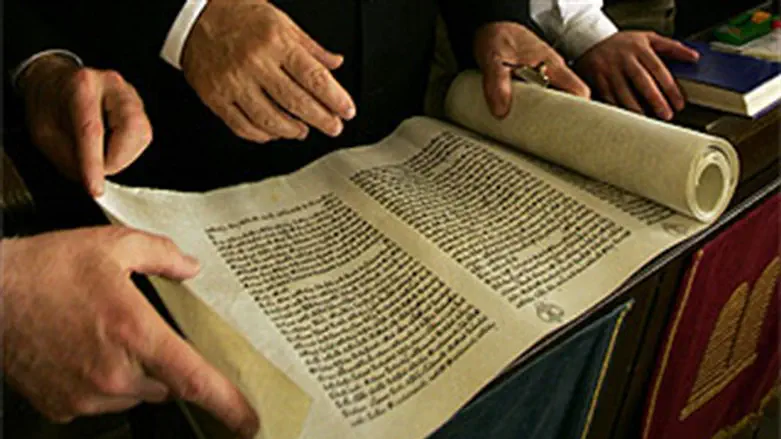

To avoid getting into a whole megillah, this brief summary, which includes selections from the midrash, assumes some basic acquaintance with the Biblical Book of Esther (Megillat Esther). The key in the Orthodox Jewish understanding of the book is that Mordechai wanted to circulate it throughout the empire, but he knew it had to get past the King and his censors.

Any offending word or implication in the text not only might condemn the book to be barred, but it might also get him killed by royal decree. Therefore, Mordechai wrote it in a way that much of the narrative is implied “between the lines” but not explicitly stated. The Talmudic traditions therefore fill in the missing parts of the story.

Key points:

Mordechai wrote it in a way that much of the narrative is implied “between the lines” but not explicitly stated. The Talmudic traditions therefore fill in the missing parts of the story.  The King actually hated Jews. He is the Achashverosh who stopped the Jews from rebuilding the Holy Temple in Jerusalem (Ezra 4:6) after King Cyrus of Persia had permitted its rebuilding. In marking his third year on the throne, the King he held a massive six-month celebration, followed by a ribald seven-day feast. As he got drunk, he and friends started arguing over which province had the most beautiful women.

The King actually hated Jews. He is the Achashverosh who stopped the Jews from rebuilding the Holy Temple in Jerusalem (Ezra 4:6) after King Cyrus of Persia had permitted its rebuilding. In marking his third year on the throne, the King he held a massive six-month celebration, followed by a ribald seven-day feast. As he got drunk, he and friends started arguing over which province had the most beautiful women.

Somehow, he decided to prove his point that the home-grown were most beautiful by commanding his anti-Jewish wife, Queen Vashti, to present herself in the nude, wearing only her crown. She refused to do so, particularly after being smitten with a full-body rash (a measles-vaccine-denier?), and also sent the King a sharp note that accused him of being a lowly drunk unlike her father, the former king of Babylonia, who could drink heavily and never lose sobriety. The King got furious and, after consulting with his equally sauced friends at the drinking party, ordered her executed.

Three years later the King, now sober, was lonely and wanted a new queen. He conducted a national search. All single women were commanded to present themselves in the capital. Hegai, a royal chamberlain and undoubtedly a eunuch, was in charge of overseeing the tens of thousands of single women arriving, picking out a few dozen or hundreds for the king to “try out” and preparing each finalist for her respective “big night” by having each treated with skin softeners, lotions, perfumes, and cosmetics for a year. All the others were sent home. Those whom Hegai selected each spent one night with the King for a “try-out” in bed.

One would be selected Queen; all other finalists would be condemned for the rest of their lives to the harem overseen by another royal chamberlain eunuch, Shaashgaz, because no man in the kingdom was permitted ever to be intimate with a woman who had been intimate with the King. So it was all-or-nothing if selected by Hegai as a finalist. Esther’s night was in January, which proved miraculously helpful in a Middle Eastern era before air conditioning and indoor plumbing. While a summer’s day and night could be hot, sweaty, causing body odor and make-up to run, a winter night could be better for various reasons.

Esther was chosen Queen but never revealed her ancestry or religion.

The King himself had come from lowly origins and was a boor. He had married the daughter of a former Babylonian king, and she constantly shoved that status difference in his face. There was something enticing for him in now having a wife whose ancestry was possibly even lower than his. She would never throw her lineage in his face as had the previous one, and she was an orphan. No in-laws to deal with, another plus. (An aside: What is the difference between in-laws and out-laws? Answer: Outlaws are Wanted.)

Mordechai the Jew secretly was Esther’s uncle (or cousin, or husband, depending on the rabbinic interpretation). He hung around the palace courtyard, a public square, to keep tabs on Esther.

As a primary religious leader of the Jews, who had been among those exiled from Israel by Babylonia’s King Nebuchadnezzar (Esther 2:6), Mordechai also was fluent in dozens of exotic languages. Two of the King’s chamberlains, Bigtan and Teresh, plotted to assassinate the King because he had shunted them aside after marrying Esther. They plotted out loud, speaking in a language no one there possibly could have known — except for Mordechai. He reported the plot to Esther, who told the King and emphasized that she heard it from Mordechai the Jew.

The report was investigated, confirmed, and the two connivers were hanged. (Note the difference from a Mueller/Adam Schiff investigation: not two years with a hundred indictments of people with nothing to do with anything, but quick, elegant, to the point, and finished.)

The King elevates an aide, Haman, to be vizier. Haman expects everyone who sees him to bow down to him. Mordechai the Jew, a descendant of the tribe of Benjamin, uniquely will not bow down. Among Jews, the tribe of Benjamin had a particular pride that their progenitor was the only son of Jacob who never had bowed down in his life, because all the others had bowed down to Esau. (Gen. 33:2-3)

A date was set for the mass murders, to be eleven months thence. Weapons from the King’s arsenal would be distributed to Jew-haters throughout the Kingdom. Haman decided he wanted Mordechai and his people dead. The King already hated the Jews, so acquiesced. A date was set for the mass murders, to be eleven months thence. Weapons from the King’s arsenal would be distributed to Jew-haters throughout the Kingdom. Esther, in her ivory tower, knew nothing of what was going on.

Haman decided he wanted Mordechai and his people dead. The King already hated the Jews, so acquiesced. A date was set for the mass murders, to be eleven months thence. Weapons from the King’s arsenal would be distributed to Jew-haters throughout the Kingdom. Esther, in her ivory tower, knew nothing of what was going on.

When Mordechai heard the news, he mourned, donned sackcloth and prayed outside the town square. Queen Esther heard from her most trusted aide, who knew her relationship to Mordechai, that Mordechai was publicly mourning for some reason. In messages exchanged back and forth between the Queen and Mordechai via the aide, she learned from Mordechai about the planned mass murder of Jews. She was unsure what to do. He told her to speak to the King and save the Jews. She replied that the King does not see people unless he asks for them, and he executes anyone who disturbs him when not summoned unless, upon seeing them, he is amused and signals by raising his gold scepter that the person should not be slaughtered.

Since the King had not asked to see her for thirty days, Esther sent word to Mordechai that it would be suicide for her to go to the King on her own initiative. He replied by messenger that G-d arranges life developments for reasons, and maybe this moment of peril is the reason for which she miraculously was chosen to be Queen; moreover, if she does not stand up now for her people, she will be the one who ends up dead, and G-d will just have to send another person miraculously to save the Jews.

Chastened, she agrees to risk her life but asks that Mordechai first order the entire Jewish population to fast and pray for her for three days, into the first day of Passover, the day that the Jews were freed from Egyptian bondage. The public three-day fast ensues, and she risks all. The King sees her at the doorway, is amused, and raises his gold scepter, welcoming her and asking what she wants.

Esther does not blurt out the situation. Instead, her strategy is to convince the King that, with him not paying attention to her these past thirty days and more, Haman has been taking a fancy to her, and maybe something now is going on between them. Maybe not. So she invites the King to a private feast with lots of wine — his favorite food supplement — and it will be special and intimate: only the King and her. Just the two of them. And also Haman.

At the feast, the King asks Esther whether she would like anything special, and she answers that all she desires is that the King come to another party like today’s — again romantic, intimate, and only the King and she. And Haman.

That night the King cannot sleep. It is driving him nuts: “What’s with Esther and Haman? Are they going to kill me tomorrow when I am drunk at the party, sort of like in Hamlet?” He can’t sleep, so he asks to be entertained in an era before television and internet by having one of his aides read from his diary, the chronicles of his reign. The reader opens the book randomly to the section relating how Mordechai the Jew had saved the King’s life by reporting the assassination plot. The King contemplates that he has assassins all over the place — Bigtan and Teresh then, perhaps Haman and Esther now — but then he was saved by a friendly informant.

Why no informant now? It hits him: “Did I ever reward Mordechai for saving my life? If not, maybe that is the reason people do not stick out their necks to warn me.” He asks the guy reading the diary, and the guy says that Mordechai never was rewarded.

As this exchange ensues, Haman shows up in the King’s courtyard in the middle of the night to ask permission to hang Mordechai the Jew on a gallows he just erected for him in his backyard. The King, wondering whether this maybe-assassin was there at midnight to kill him before tomorrow’s party, is flustered and asks Haman, hoping also to delay any assassination now by implying that the King has big things planned for Haman: “Look, let’s say there is one guy in the kingdom I want to honor extra-special, how would I do it?” Haman, assuming the King means him (and having no idea that the King thinks he wants to kill him), suggests a massive parade on which the King’s favorite guy can wear robes the King has worn and can ride on a horse the King has ridden.

The king says “Great idea! Do all that for Mordechai the Jew, and you lead his entourage.” Haman cannot figure it out but realizes this is not the time to ask permission to hang Mordechai. At the next day’s parade, the retinue passes by Haman’s home, where his daughter on the balcony assumes that Dad is on the horse and that Mordechai is on the ground, leading the way. She spills the contents of her chamber pot onto the head of the guy in front of the horse. When she learns it was her father she shamed, she jumps in anguish to her death.

At the next day’s wine feast, when the King is sauced, Esther reveals for the first time that she is a Jew, and she tells the King that Haman is the enemy of all that is good and plans to kill her and all her people. Haman is shocked that she is a Jew and realizes he is in big trouble. Haman starts begging Esther to understand that it all is a misunderstanding, and he starts shaking uncontrollably.

The King, who regularly orders people executed when he gets angry while drunk, steps outside for a moment to make sense of what is going on: “So she is not plotting with Haman to kill me? Haman is plotting to kill her? She is a damned Jew? But I like her. So what does that mean, that I like Jews? And that means that the guy who saved me from the assassination also was a Jew? So I like two Jews? But I don’t like Jews, and they know it, so why do they like me?”

As he walks back in, Haman — who was shaking uncontrollably — has slipped (or been pushed by a Divinely dispatched Angel) onto Esther’s couch, landing on her accidentally. The King sees this through his drunk stupor and cannot figure out whether Haman is trying to kiss her or rape her or strangle her — all of which are unacceptable. At this moment, as he thunders at Haman “You’re going to overcome the Queen with me in the palace?” the King’s attendant, Charvonah, tells him: “And by the way, this same Haman has erected a gallows in his backyard to hang Mordechai who saved your life.” The King blurts out: “So hang Haman on it instead!” They hang Haman.

The Jews kill their armed enemies but not women or children (9:6,15-16), and they do not take any spoils.  The King transfers Haman’s estate to Esther and Mordechai. He authorizes the Jews to kill all their enemies. With two royal decrees now on the record — (i) the earlier one authorizing the Jew-haters to kill the Jews, including women and kids, and to take all the spoils, and (ii) the other identical decree authorizing the Jews to kill the Jew-haters, including women and kids, and to take all their spoils — the local government officials have to figure out which pogrom to support and which to suppress. As they learn that Mordechai now is paraded publicly as the King’s vizier (8:15), while Haman is hanged, they support the latter decree while suppressing the former.

The King transfers Haman’s estate to Esther and Mordechai. He authorizes the Jews to kill all their enemies. With two royal decrees now on the record — (i) the earlier one authorizing the Jew-haters to kill the Jews, including women and kids, and to take all the spoils, and (ii) the other identical decree authorizing the Jews to kill the Jew-haters, including women and kids, and to take all their spoils — the local government officials have to figure out which pogrom to support and which to suppress. As they learn that Mordechai now is paraded publicly as the King’s vizier (8:15), while Haman is hanged, they support the latter decree while suppressing the former.

The Jews kill their armed enemies but not women or children (9:6,15-16), and they do not take any spoils.

In recording the hanging of the ten sons of Haman (9:10), who are among the Jew-haters killed, the traditional Hebrew writing in the parchment scroll records certain letters in certain of their names in smaller font (9:7,9). No one has known why for centuries. The smaller letters — tav, shin, and zayin— also represent numbers aggregating to 707 and is the way that the Hebrew Calendar Year 5707 (corresponding to October 1946-September 1947) is written. As it just-so-happens, on October 16, 1946, ten former Nazis were hanged for war crimes by order of the Nuremberg trials. Among his last words upon being hanged, the Nazi Julius Streicher curiously shouted out “Purim Fest 1946!”

Purim particularly commemorates that, even when miracles are not overt, G-d watches over and peforms miracles. One just has to look more closely, with “Night Goggles of Faith,” to see them.