I remember the moment when, at fifteen, the study of Talmud was transformed within me from a chore and an assignment into a joy and a spiritual experience.

The organizations that claim to represent American Jewry met this month in their annual General Assembly gathering. Once every five years this meeting takes place in Jerusalem, while rotating around American cities the other four years of the cycle. Surveying the wreckage of much of current American Jewish society, there is now a call for a much more soulful approach to Judaism and Jewish life to help reverse current trends and demographic and social realities.

For decades, official American Jewry has been trapped by its own public relations sloganeering. No one can be against a more soulful Jewish public. But what exactly does the word soulful mean? In what context is the word to be translated into deed and attitude? In short, what and where is the key to reaching and opening the shriveled soul of American Jewish society?

Truth be said, it does not appear to be in the existing structure of organized Jewish life in America. Organizational meetings, banquets, dinners and conferences are all important events but none of them really create a soulful atmosphere. The scruffy business of fundraising and organizational turf protection or expansion all gets in the way of soulfulness.

This, by the very nature of the matter, apparently cannot be helped or avoided. But it is a reality that should be recognized. It is apparent that it is outside of the realm of official organized Jewish leadership that soulfulness must be created and pursued. Organizational life, no matter how efficiently structured and well-intentioned can only achieve practical results in the physical world. It is too sterile an enterprise to affect the soul.

In Jewish tradition the house of worship, of prayer, was meant to be a soulful place. It was not meant to be a place of entertainment or even of the mere fulfillment of a religious obligation. It was meant to be a place where one could converse with one’s own inner self and thereby with one’s Creator. It was and is governed by physical rules and set texts in order to help the one praying to achieve that goal of inner and lofty communication.

But the rabbis characterized it as a place of “kavanah” – a Hebrew word that almost defies translation because of its exquisite sense of nuance. The word is loosely translated as direction or intent or concentrated fervor, but in terms of prayer it really signifies connection with one’s own soul and thereby with its Creator.

I have experienced such a place a few times in my lifetime. The first was as a child in my father’s large synagogue in Chicago on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur when the synagogue was filled with Eastern European Jews and their prayers rose as a storm sweeping all before it. Their roar of anguish and awe was a soulful experience.

Later in life I read about the experience of the great Jewish philosopher Franz Rosenzweig serving with the German army in Poland in World War I. A completely assimilated German Jew, engaged to marry a non-Jew, he wandered into a small nondescript synagogue in a Polish village on Yom Kippur night and the experience of that prayer service transformed him forever. Our synagogues and prayer services are certainly sterile and cold in comparison.

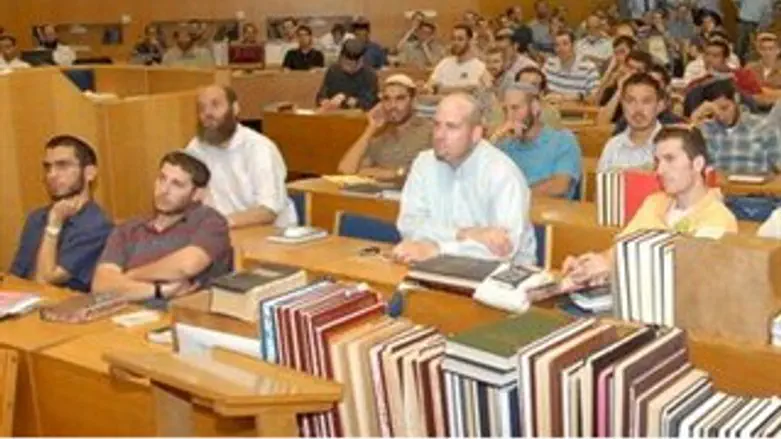

The house of study was also meant to be a place of soulful inspiration. I remember the moment when, at fifteen, the study of Talmud was transformed within me from a chore and an assignment into a joy and a spiritual experience, I had teachers that enabled me to feel that way and that allowed me to draw inspiration from the white spaces and not only from the black letters on the page.

Torah study was meant not only to provide necessary knowledge but it also, just as importantly, was meant to create a conduit to one’s own soul and being. That is why the rabbis stated that there were seventy facets to every word and idea of Torah. Every individual finds a different facet of spirituality to attach one’s self to. There is no one size fits all when it comes to matters of the soul.

But the ignorant and unlettered – tragically, most of American Jewry - are almost automatically precluded from such an attachment; the Torah for them remains an unexplored and forbidding dark continent. It is within the synagogue and the study hall that soulfulness in Jewish life can be regained and fostered.

It will require new ideas and tactics, much determination, and human and capital investment to achieve this. But the Jewish soul is not dead within us. It needs nurturing and will. Maybe organized Jewry will yet devote its talents and resources towards this pursuit of soulfulness and not continue to flounder in slogans and the wilds of organizational life.