Princeton University spent months planning an exhibit of 19th-century American Jewish art before cancelling the show because two of its featured artists had supported the Confederacy.

The cancellation has drawn criticism from the exhibit’s Jewish donors and consulting historians. They say the decision “rewrites art history.”

“I was really stunned by the university taking this position,” Leonard Milberg, the Jewish financial manager and art collector who funded the collection and whose name adorns the gallery where the exhibit was to be shown, told the Princeton student paper.

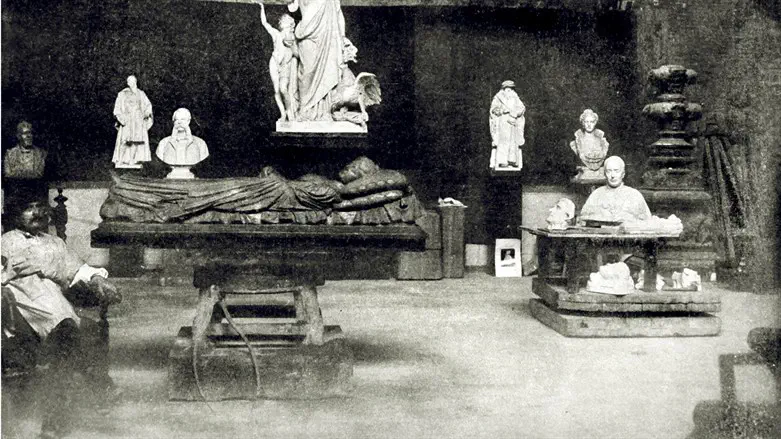

The exhibit was to feature the work of Moses Jacob Ezekiel, a renowned sculptor who also crafted the Confederate Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery and hung the Confederate battle flag in his Rome studio for his entire career, and painter Theodore Moise, who was a major in the Confederate Army, among other artists.

A famous Ezekiel sculpture known as “Faith,” an adaptation of an earlier work “Religious Liberty” commissioned by B’nai B’rith that celebrates the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence and is currently displayed outside the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, was to be the exhibit’s centerpiece; another Ezekiel work was to feature a sculpture of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, the founder of American Reform Judaism.

After first agreeing to organize the exhibition last summer, Princeton canceled the show in December. According to emails first obtained by Religion News Service, the university’s vice provost for institutional equity and diversity had expressed concerns over the Confederate links and had asked for Ezekiel and Moise to be substituted for other artists.

That decision didn’t sit well with Milberg, the show’s curator Samantha Baskind or the Jewish historians they consulted for the exhibit, Adam Mendelsohn and Jonathan Sarna, who argued that the exhibit as planned had addressed the artists’ Confederate associations in a thoughtful manner.

“The donor pulled out because Princeton canceled the art,” Baskind told the Daily Princetonian, saying that the decision was “an unfortunate anti-intellectual surrender to cancel culture.”

She added, “Removing the artists with Confederate ties rewrites art history. Art historians examine the meaning of art in its own time as well as how it’s perceived in the current moment. We need to inform and discuss the past, not bury it.”

American institutions, including universities, have increasingly reevaluated whether and how to acknowledge racist figures in their past. That effort has included, at times, Jews with ties to the Confederacy: A Northern California synagogue, for example, has weighed whether to include Jewish Confederate leader Judah Benjamin in an engraved list of illustrious Jews.

In an op-ed, Milberg noted that he had previously sponsored Princeton exhibits spotlighting artists with antisemitic ties. “I felt that I should not erase history but learn from it,” he wrote.