There’s a crisis in American Jewish leadership and it involves the misuse of communal authority to sanction dogmatic politics.

As reported in the Jewish media in December, a scheduled speaking engagement by Professor Alan Dershowitz was cancelled at New York’s Temple Emanu-El, a prominent American Reform congregation. The temple rescinded an invitation to the staunchly pro-Israel Dershowitz but welcomed Peter Beinart, whose hostile views on Israel are perhaps more consistent with the progressive intellectual elite.

Capricious rationalizations aside, progressive anti-Israel antipathy is not justified by revisionist Palestinian Arab history or as a response to Israeli social policies, which often tend to comport with liberal sensibilities. Nor is it emblematic of traditional Jewish introspection. The rejection of Jewish nationhood and tradition arises from political bias and the discarding of values that historically shaped Jewish moral and social conduct.

It is also fueled by the urge “to pass” that has afflicted culturally ambivalent Jews since Napoleon tore down the ghetto walls.

Though once thought of as the desire to blend in quietly, trying “to pass” today often demands the public embrace of political ideologies that defy Jewish tradition. There is nothing quiet about such conduct. Too often, the liberal establishment disparages traditional Judaism as ethnocentric and trivializes Jewish history by reducing it to partisan allegory, while failing to demand adherence to traditional beliefs as a guide for daily living.

Though once thought of as the desire to blend in quietly, trying “to pass” today often demands the public embrace of political ideologies that defy Jewish tradition. That this state of affairs would become the norm would have disturbed my father, who was a child of the early-twentieth-century immigrant experience. Both his parents were born in Europe and came to the US to escape persecution; and while traditional observance may have dissipated among many of his generational peers, certain beliefs were immutably ingrained. Most of his secular age contemporaries would have been hard-pressed to explain why they could not bring themselves to eat cheeseburgers, for example, but such prohibitions remained cultural touchstones.

That this state of affairs would become the norm would have disturbed my father, who was a child of the early-twentieth-century immigrant experience. Both his parents were born in Europe and came to the US to escape persecution; and while traditional observance may have dissipated among many of his generational peers, certain beliefs were immutably ingrained. Most of his secular age contemporaries would have been hard-pressed to explain why they could not bring themselves to eat cheeseburgers, for example, but such prohibitions remained cultural touchstones.

I took for granted the singular focus of my father’s worldview because of his clarity of vision. He would ask what we learned in cheder every week, he’d be absent from the dinner table when attending synagogue meetings or communal events, and he’d regale us with stories about itinerant fundraisers who regularly visited his office (and never left empty-handed). Learning by observing how he lived life was easy, but I only realized the depth of his convictions by the way he died.

My father became ill when he was fifty-six years old and passed away less than a year later, but he continued to operate his law office until a month before succumbing to his illness. He had an active practice and needed help to keep things running as his energy and stamina diminished. I had recently graduated college and had no job, so I became his assistant, driving him around, learning how to search land titles, and performing general office tasks. We spent a lot of time together, and during this period I witnessed his soul shine brightly.

He was in and out of the hospital for months during that year; and as the frequency and duration of his hospitalizations increased, he realized his time was growing short. I was with him when the doctor said there was nothing more that could be done. My father, however, did not outwardly bemoan his fate. Rather, he shook his doctor’s hand and thanked him for doing the best he could. I’d never before seen a doctor reduced to tears.

Similarly, my father didn’t ask “why me,” or curse his situation. Instead, he told me there is a reason for everything, though we might not always understand; and by these words he demonstrated his faith in Hashgacha Pratis – that the world functions under G-d’s constant supervision. Absorbing such principles from rabbis and teachers was one thing, but seeing my father embrace them under desperate circumstances was something else entirely.

What happened next made a greater impact still. After the doctor gave him the devastating news, my father called me and my three brothers to his bedside and blessed us the same the way that Yaacov (Jacob) blessed his sons from his deathbed near the end of Sefer Bereishit (Genesis). I don’t think he was consciously following the Torah’s narrative as a script, but its model for conduct was so ingrained in him that he could not have done otherwise. Or maybe it was because he shared his name, Yisrael, with this particular patriarch. Whatever the reason, it evidenced his place in the unbroken chain of transmission going back to the forefathers.

After his final diagnosis, my father asked me to come to his hospital room with a dictating machine and notepad because he still felt responsibility to his clients and wanted to assure their needs would be served appropriately. We worked until late at night when he finally said, “that’s enough.” So, I asked, “do you want to go to sleep?” And he said, “no, I’ll soon be asleep for a long time, and I’m going to miss you guys when I am. Let’s just talk.” And so we did through the night – discussing things important and mundane, confidential and exoteric – until we both nodded off.

The things he told us during those days conveyed his unwavering Jewish perspective – his belief in G-d’s hashgacha, the immortality of the soul, and the relevance of Torah values for daily living. The words he spoke demonstrated how deeply these beliefs were embedded in him, but they were not surprising given his upbringing.

He and his brothers were raised by old-world parents who did not want their children to be constrained by old-world limitations. Unlike contemporaries who tried to pass in America, they never attempted to redefine Jewishness or diminish its historical uniqueness. Thus, my father’s outlook was shaped by heritage, custom, and tradition rather than the urge to blend into the woodwork.

Unfortunately, not all Jews felt this way; and the desire to emulate common culture influenced the development of the nontraditional and secular communal establishments. As early as 1837, the first Reform rabbinical conference in Wiesbaden, Germany rejected the primacy of Halakha (Jewish law), ritual observance, and belief in messianic redemption. In renouncing normative tradition, the early Reformers proclaimed Berlin as their Jerusalem and the synagogue as their Temple; and their attempt to redefine Judaism as a deracinated religious persuasion purged of its ethnic and national roots was a significant step towards assimilation.

The Reform movement in the US followed suit before the end of that century. At its 1869 Philadelphia Conference, the American reformers likewise rejected ritual law and messianic belief, stating: “The Messianic aim of Israel is not the restoration of the old Jewish state under a descendant of David…” They went further at their 1885 Pittsburgh conference, where they dispensed with Jewish national identity altogether and issued the “Pittsburgh Platform,” which attempted to redefine Jewishness thus: “We consider ourselves no longer a nation, but a religious community; and we therefore expect neither a return to [the homeland], nor a sacrificial worship under the sons of Aaron, nor the restoration of any of the laws concerning a Jewish state.”

Though the Reform movement reembraced Jewish nationhood in its 1937 Columbus Platform, perhaps as a reaction to what was happening in Nazi Germany, the secular and non-Orthodox establishments continued to conflate Jewish identity with political ideals that often contradicted traditional Jewish law and historical claims.

The difference between my father’s values and those of the ritually liberal movements is that his were authentic links in a chain of tradition not shaped by the desire to accommodate outside sensibilities. In contrast, the ideals embraced by the non-Orthodox and secular movements were often responses to external stimuli, e.g., European enlightenment, sudden freedom from the ghetto, or a yearning for acceptance by the non-Jewish world. The early reformers wanted to create something that seemed less alien and more acceptable to gentile society by redefining Judaism according to ideologies that were not inherently Jewish. They thus sought to sacralize the temporal.

The values my father held dear, however, were innately and organically Jewish – they were not sophistic constructs resulting from strained rationalization, intellectual artifice, or existential angst in a post-enlightenment world.

Before he died, my father told me to always act like a Jew and never try to pass. He needn’t have verbalized these admonitions because they were clear from the way he lived life and approached death. Nevertheless, parents need to exhort, and children need to listen – particularly when the message seeks to preserve continuity of belief, heritage, and culture. When the message draws on extraneous value systems or partisan hackery, however, it will preserve nothing.

Communal leaders, take note.

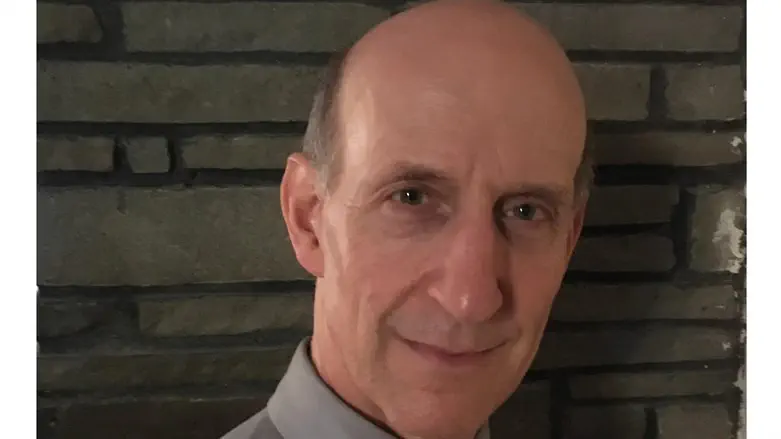

Matthew M. Hausman is a trial attorney and writer who lives and works in Connecticut. A former journalist, Mr. Hausman continues to write on a variety of topics, including science, health and medicine, Jewish issues and foreign affairs, and has been a legal affairs columnist for a number of publications.