The concept of the “Righteous Gentile” is originally rooted in the Torah’s recognition that members of other nations can serve the G-d of Israel by accepting and faithfully observing the Noahide Commandments. Known as “Gerei Toshav” (resident foreigners) in ancient Israel, “pious people of the world” were honored for renouncing idolatry and attaching their destiny to the Jewish nation.

In modern times, the term was applied to people who saved Jews from genocide during the Holocaust, regardless of whether they accepted the seven laws of Noah; but more recently it has been imbued with political connotations by those seeking Jewish validation for partisan agendas. For many secular liberals, the term refers to those who embody progressive ideals that are often inconsistent with or extraneous to Torah values.

To determine who can truly be called a Righteous Gentile, one must understand the scriptural basis and historical evolution of the concept and the character of those to whom it traditionally applied.

Given its classical meaning, the term would certainly include Noahides who reject idolatry and embrace the Torah. Their virtue is reflected not only in their faith, but in their recognition of the Jews as a “light unto the nations” and passionate belief in Jewish spiritual and national integrity. Many of today's B’nai Noach are outspoken in their support for Israel and opposition to the growing evangelical threat against Israeli and Diaspora Jewry.

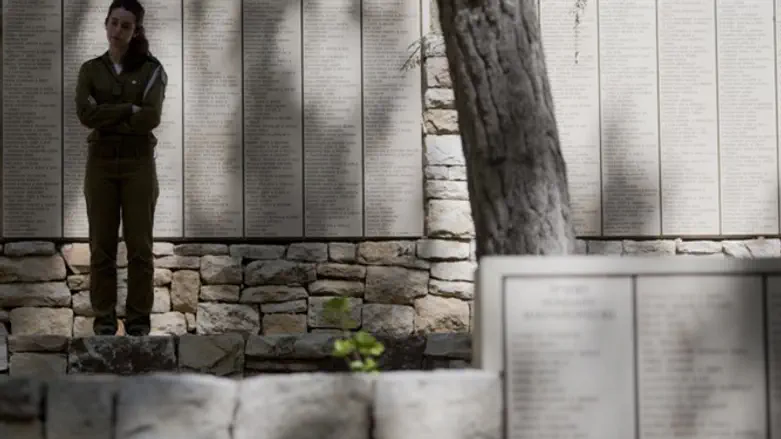

During and after the Second World War, the title “righteous among the nations” was conferred upon those who saved Jews from the Nazis and their collaborators. It was not based on religious belief but on commitment to saving Jews from extermination. Raoul Wallenburg and Oskar Schindler were among those who acted at great personal risk – and without ulterior motive – to rise above a common European culture steeped in ancestral antisemitism. And they were not alone. Yad Vashem in Jerusalem honors more than twenty-seven thousand non-Jews for acts of bravery and moral courage during the war.

But did simply saving Jews physically constitute a righteous act? If this were the only criterion, those who saved Jews for impure reasons would be honored as righteous. This was certainly a concern with respect to Jewish children who were taken in by convents, monasteries, and churches, baptized against their will or without understanding, and then effectively kidnapped after the war pursuant to a 1946 Vatican directive forbidding their return to surviving family members. The Church’s motivations were rooted in the same doctrinal hatred that paved the way for the Nuremburg Laws and Holocaust; and the complicity of priests, nuns, and laypeople who exploited parental anguish excludes them from honorable recognition. They may have saved children from the gas chambers, but they crippled them spiritually.

Those who are obsessed with redefining the Righteous Gentile as a political exemplar devoid of traditional meaning or historical context would do well to discover and embrace the Righteous Jew first. It takes one to recognize the other.

Catholic apologists engage in historical revisionism to suggest that the Church worked to save Jews during the Shoah – despite much evidence to the contrary – and some even argue against all reason that Pope Pius XII should be considered a righteous gentile. Such sophistry is understandable coming from an institution attempting to conceal its past sins. It is unfathomable when spouted by social and political activists who apply the term to people who supported the Nazis, but whose descendants are now allied with the progressive left in its fight against western values and Israel.

It has become increasingly common to hear progressive rabbis praise Arab or Muslim efforts to save Jews during the Holocaust, though such instances were extremely rare, especially when compared to the myriad acts of heroism that occurred throughout Europe. They often expound thus in broad strokes without providing specific examples in a pattern that seems to parallel their embrace of the Palestinian national myth or relationships with putative human rights groups that have covert extremist or Islamist sympathies.

These tales are exaggerated at best.

The real history is far less noble than they would have their audiences believe. Saving Jewish lives was not generally a priority in the Arab-Muslim world, much of which approved the German war effort. Rather than empathize with Hitler’s victims, many chose to serve German interests, e.g., by joining Waffen-SS Hanjar units that were personally recruited by the Mufti of Jerusalem and instrumental in the extermination of Balkan Jewry. Their complicity was consistent with the Mufti’s desire to implement the Final Solution throughout the Mideast, which likely would have happened had Rommel not been defeated at El Alamein.

Equally catastrophic was the collusion of Arab leadership in preventing the escape of Jews from Europe by influencing the British to block refugees from immigrating to their ancient homeland and thus condemning men, women, and children to the death camps. This complicity is glossed over by revisionists seeking to obfuscate the cultural past of people whose social and political causes are now advocated by the liberal mainstream.

The sparse representation of Muslims in Yad Vashem says more about the reality than the stories told in many nontraditional congregations. The roster of more than twenty-seven thousand gentiles recognized as “righteous among the nations” includes only a few Muslims, mostly from a single country – Albania.

Progressives who deny the complicity of Arab leadership during the Shoah often demean the memory of its victims by frivolously branding all political opponents “Nazis” or using the Holocaust as partisan metaphor, e.g., comparing illegal immigrants to Jews trying to escape genocide, equating southern border detention centers to death camps, or analogizing the abrogation of Jewish civil rights in prewar Germany to the struggle for gender equality in the US.

Immigrants fleeing poverty or political unrest in South America cannot be compared to Jews who were marked for death. False analogies are particularly shameful when voiced by liberal rabbis or communal leaders whose statements provide cover for left-wing antisemites.

Such sentiments and platitudes are now used within the mainstream establishment to define righteousness and glorify ideologues whose platforms threaten Jewish continuity and the State of Israel. Possible explanations for this sad state of affairs include an alarming rise in Jewish illiteracy among the non-Orthodox, the false conflation of Jewish tradition with progressive politics, and pathological self-loathing.

But just as traditional values and history cannot be rewritten to legitimize ideologies that disparage both, neither can the Jewish concept of righteousness be molded to fit people whose values, priorities, and preoccupation with “social justice” threaten the Jewish future.

The mantle of righteousness cannot be bestowed on churches that exploited the Holocaust to steal children from their families and suppress their heritage. Neither can it be conferred upon those among the evangelicals who claim to love the Jews and their nation while surreptitiously seeking their spiritual destruction by preying on the educationally weak and vulnerable. And it certainly cannot be applied to activists who endorse political agendas that delegitimize Israel and imperil Jewish continuity.

If the concept of the Righteous Gentile was originally associated with salvation and based on the premise that non-Jews have a place in the world to come, then it is inextricably linked to the belief in messianic redemption. And if the concept as defined after the Holocaust was predicated on the Jews’ physical deliverance, then it presumes a recognition that Jewish continuity is vital to the world and must be preserved.

Consequently, the concept of the Righteous Gentile – whether defined by adherence to the Noahide laws or commitment to preserving Jewish life – is connected to the Jews’ yearning for the messianic age. Indeed, this was prophesied by Zechariah ha-Navi after the return from the Babylon more than 2,500 years ago, when he wrote: “Thus said the Lord of Hosts: In those days, ten men from nations of every tongue will take hold—they will take hold of every Jew by a corner of his cloak and say, ‘Let us go with you, for we have heard that G-d is with you.’” (Zechariah, 8:23.)

In contrast, the values that progressives use to define righteousness today – when analyzed against the spectrum of history – would ultimately lead to a future in which the Jewish people and nation would cease to exist.

Those who are obsessed with redefining the Righteous Gentile as a political exemplar devoid of traditional meaning or historical context would do well to discover and embrace the Righteous Jew first. It takes one to recognize the other.

Matthew M. Hausman is a trial attorney and writer who lives and works in Connecticut. A former journalist, Mr. Hausman continues to write on a variety of topics, including science, health and medicine, Jewish issues and foreign affairs, and has been a legal affairs columnist for a number of publications.