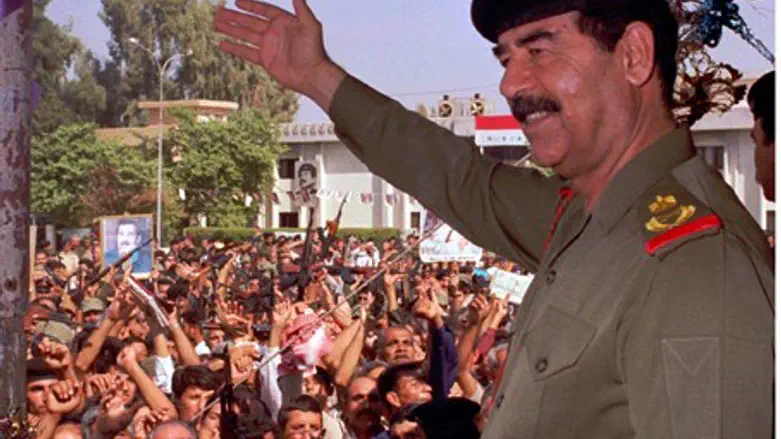

Dozens of Iraqis crowding a Baghdad street fought to glimpse the red-haired man in a glass coffin, hoping to witness the end of a long-feared member of Saddam Hussein's regime.

The furore over the dead man - who might be Saddam's deputy Izzat Ibrahim al-Duri, though his identity has still not been determined - is yet another sign of the influence the dictator exercises in Iraq more than 12 years after his overthrow.

Saddam and his Baath party still haunt Iraqi politics, where links to the former regime can wreck careers, as well as battlefields across Iraq where his former officers have played major roles in militant groups fighting the new government.

Pro-government forces killing the man who may be Duri was "no less important" than the 2006 execution of Saddam himself, said Sheikh Jassem al-Jazairi, an official in the Ketaeb Hezbollah Iranian-backed militia, which handed over the body to the government.

Shouts of "Death to Baathists" accompanied the body's departure in an anonymous white van after the chaotic handover, which was guarded by dozens of heavily armed masked militiamen backed by Saddam's nemesis Iran.

The Baath took power in a 1968 coup, dominating the country until the overthrow of Saddam's regime by the 2003 US-led invasion.

But "the Baath is still active, and everyone who says the Baathists are finished and the Baath party is over defies the truth", said Ihsan al-Shammari, a political science professor at Baghdad University.

Role in insurgency

"A symbol like Saddam or Izzat al-Duri may disappear, but many of the (Baath) leaders are still active and are trying to overthrow the democratic political system in Iraq," Shammari said.

Baathists have played a major role in insurgent groups that battled US-led forces and later those of the new Iraqi government, and reportedly in the Islamic State (ISIS) jihadist group which led an offensive that overran large parts of Iraq last year.

Documents obtained by German magazine Der Spiege indicate that a former Iraqi intelligence officer, Samir Abed Mohammad al-Khlifawi, planned ISIS's expansion into Syria and its return to Iraq.

And many of ISIS's top military leaders are former Saddam-era military officers

Shammari said the documents have convinced many Iraqis that ISIS is just a front organisation for Baathists seeking to regain power.

The Army of the Men of the Naqshbandiyah Order - a Sunni militant group with close ties to Duri - also took part in the IS-led drive in 2014.

Iraq has sought to reduce the influence of Saddam's regime in the post-2003 state via "de-Baathification".

That process and its successor, the Justice and Accountability Commission, dealt with 130,000 cases and barred more than 17,000 people from government, commission chief Bassem al-Badairi said.

But critics say de-Baathification has been used by the Shia-led government to victimize Iraq's Sunni Muslim minority, which dominated Saddam's regime.

Some Saddam-era officers are still serving in the security forces, but other soldiers were put out of work - especially under American viceroy Paul Bremer's decision to disband the army in 2003 - fueling the anti-government insurgency.

Career-ending song

Abu Mutlak, a staff lieutenant general under Saddam, said he has been reduced to driving a taxi to support his family, and that bitterness over their treatment drove some former colleagues to fight.

"How do you want me to take part in building a new political system that dismissed me from everything and robbed me of everything?" he asked.

Even seemingly insignificant associations with the former regime can still wreck careers. .

Rafid Jaboori, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi's spokesman, resigned last month after a video emerged showing him singing a song praising Saddam more than a decade earlier.

Saddam's regime also lives on in the pain and suffering it caused to its tens of thousands of victims and their relatives.

"I still shudder when I hear the name of Saddam on the television or radio, not from fear, but hatred," said Aras Abed, a Kurd who lost 12 family members to Saddam's chemical weapons attack on the village of Halabja in 1988.

"I hurt a lot because of my loneliness without my family," he said.

But others remember him fondly, especially in comparison to the often-ineffective governments that replaced his regime and the rampant violence plaguing the country.

"Whenever I see his picture, my heart beats faster," said Abu Mahmud, who was a high-ranking Baath member.

His reaction to seeing today's officials on television is very different: "If they were in front of me, I would take off my shoe and hit them," he said.