Excerpted with permission from the review in Mosaic.

If you've always longed to read a book capturing that very special moment in history when the European Diaspora still was the Jewish people, even as the state of Israel was looming on the far horizon—a book explaining, from within, that moment of incipient transition into two Jewish identities—it has existed since 1930. The problem is that it was written in French, and by a Gentile at that, and for decades nobody bothered introducing it to the English-speaking public.

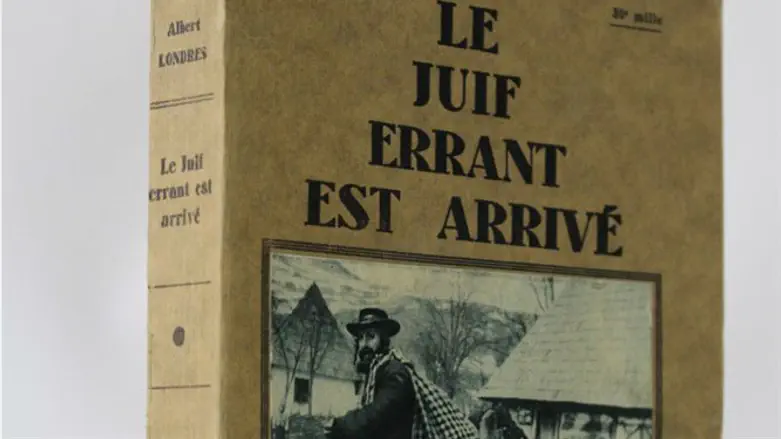

But now the situation has been rectified. Albert Londres' masterpiece, The Wandering Jew Has Arrived, has recently been published in a superb translation by Helga Abraham, an Egyptian-born graduate of Edinburgh University who now lives in Jerusalem. In her foreword, Abraham goes so far as to compare Londres with "such great documentarians as Mark Twain and George Orwell." I couldn't agree more.

...Some journalists are good at spotting things. Others know how best to relate what they have seen. Still others are adept at interpretation. Londres was all of these and more: he was a fearless investigator. In a world still dominated by the written word, he also made full use of the rhetorical and dramatic techniques inherited from the great 19th-century realist novelists: people would wait for his daily dispatches the way today’s millennials look forward to new episodes of Game of Thrones, and would buy and read them again when issued as books in modified or expanded versions.

In the 1970s, Londres’ books were republished and have stayed on the French best-seller lists ever since. All bones and muscle, and no fat, they have not aged a day.

...The Wandering Jew Has Arrived, whose main subjects—the Jewish people’s struggle for survival and the Jewish-Arab dispute in the Holy Land—are still very much in the news, is unquestionably a book from the past; but it is also, in many ways, a book about the present.

As a“concerned journalist” in the 1920s, Albert Londres could not ignore what was then known as the “Jewish question.” In the 19th and early 20th century, Jews had experienced a phenomenal demographic growth, from about three million around 1800 to about fifteen million by 1925. Many had also climbed the social ladder, especially in the new niches created by the first and second industrial revolutions. But anti-Semitism had grown right alongside, and followed them everywhere.

For the anti-Semite, Londres wrote tersely, “the Jewish passerby is stealing his air.” Accordingly, anti-Semitism involved not just exclusion or discrimination or forced conversion, but death...

...In the wake of the 1927 Rumanian pogroms, Londres undertook a grand tour of Europe and the Middle East to explore the “Jewish question” and to consider its “solution”: namely, Zionism. In his mind, the two issues intermingled.

....Londres was so impressed by Orthodox religiosity in Eastern Europe that he devoted several chapters to it. “The Rabbi Factory,” for instance, is a thorough description of yeshivah life. “The Miracle-Making Rabbi” is about ḥasidic leaders and their courts, including the Gerer rebbe whom he visited in Gora-Kawalria, a Warsaw suburb. And while perfectly aware of Orthodox opposition to political Zionism, he couldn’t help constantly binding together Orthodoxy and Zionism as two sides, only temporarily disjoined, of the same authentic Jewish identity.

...The next and final stage in Londres' Jewish journey was Palestine. There he fell in love immediately with secular Tel Aviv, a city "with no crosses or minarets" and much charm:

None of those American grids. The streets, squares, boulevards, avenues, intersect whimsically. It is bright, spacious, sunny, and all white. It emanates a fierce determination to leave the ghetto behind. You almost expect to see all these Jews pitched on the pavement, mouths open, lovingly imbibing liberty.

Only a few years (or a mere two weeks) earlier, everybody around him had been a timid "Israelite" in London or Paris, or a starving Jew in the Marmarosh, or a bullied Jew in Warsaw. Now they were "free men," and "pride had replaced shame." A nation deemed "parasitic" had been reborn on its ancestral soil, complete with "dentists, hairdressers, lawyers, doctors," as well as "bricklayers, road workers, shepherds, farm girls." The new Hebrews "drained swamps, cleared rocks," and everywhere "settlements followed settlements."

In the process, the men had shaved their beards, cut their side curls, and dropped their black caftans, and the women had shortened their skirts. But they had also resuscitated Hebrew itself "from the tomb of the Talmud" and turned it into an everyday language.

If this sounds like nothing so much as a Zionist fund-raising speech from the 1950s, bear in mind that Londres was one of the first outside observers to give a detailed account of what still amounted, in sheer statistical terms, to a very tiny miracle, involving 200,000 people at most.

Nor was he blind to the geopolitical difficulties surrounding the Zionist utopia. Meeting Arabs of all stripes, he was repeatedly warned that they would never countenance the rise of a Jewish commonwealth in their midst. Rajib Nashashibi, then the Muslim Arab mayor of Jerusalem—a city in which already two out of every three inhabitants were Jewish—told him that Jews could take back Palestine for the price at which the Arabs had bought it: "the price of blood."

Londres had just returned to Paris when he was told by a friend: "They are killing your Jews in Jerusalem." The 1929 Arab riots had started—ostensibly to protest Jewish prayer at the Western Wall on the Ninth of Av, the anniversary of the Temple's destruction. They soon degenerated into pogroms, just like in Eastern Europe: in Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and other places, 133 Jews were killed, often in the most sadistic way, and almost three times that number wounded or maimed.

Setting off to the Holy Land once again, Londres conducted a rigorous investigation and added two more chapters to his book. They still read today as the grimmest narrative of those events. They feature the first documented indictment of [Hajj] Amin el-Husseini, the British-appointed grand mufti of Jerusalem who was to become a Nazi supporter. But they also report individual acts of humanity and the courage of Muslim citizens or English policemen who rescued Jews and otherwise resisted the pogromists.

...What is more, despite all the difficulties and the implacable anti-Semitism, Londres ends his book on an optimistic tone. He had no doubt that "the Wandering Jew" whom he had encountered at various places in Europe had indeed arrived home in Palestine, and that Zionism was not only a feasible solution to the travails of the Diaspora but the culmination of age-old messianic hopes.

In her foreword to The Wandering Jew Has Arrived, Helga Abraham ventures that Londres would be astonished by the "bobbing-up" of ḥaredi communities dressed in 18th-century Polish fashion in the 21st-century state of Israel. I'm not so sure. I tend to believe he would welcome this development as a vindication of his own deepest views concerning Judaism. Significantly, the title of one of the book's closing chapters—a chapter on Zionism and its achievements—is: "The Joy of Being Jewish." To me the phrase has an amazingly ḥasidic ring to it.

Michel Gurfinkiel, a Shillman-Ginsburg Fellow at the Middle East Forum, is the founder and president of the Jean-Jacques Rousseau Institute, a conservative think tank in France.