Setting aside a day in the calendar, February 14, for declarations of love came late to Germans, whose warmongering leaders over the centuries primarily molded warriors for combat. The last of Germany’s dictators, Adolf Hitler, spurned the kisses and flowers of France’s La Saint Valentin and vowed to make his people “tough as leather and hard as steel."

The Nazis not only ignored Valentine’s Day, but when they launched their unprovoked wars and set into motion their planned genocide of Europe’s Jews, they canceled the Germans’ favorite holiday, Karnival, also celebrated in February.

It was not the masked balls and parades of Carnival that bothered Hitler and his henchmen. It was the poetry. The kings and kaisers of Germany had smiled indulgently at the raucous poems that criticized and challenged their authority, albeit disguised as jokes.

But the ruthless Nazis could not stand to be mocked. Nor would they allow even a glimmer of truth to contradict their propaganda. And they had warned Friedrich Kellner about that.

"The truth may not be said," wrote the justice inspector Friedrich Kellner, my grandfather, in his diary. As a Social Democrat, Friedrich had campaigned throughout the short-lived Weimar Republic against Hitler and his Nazi Party.

Before that, he was a master of ceremonies for Carnival gatherings in Mainz and would lampoon Germany’s leaders. He had fought as a sergeant in the Kaiser’s army in WWI and believed the wounds he received gave him the right to speak his mind.

Though he believed his diary would be important for future generations to know the truth about his era, Kellner, a Christian, yearned for a more active role in resisting the Nazis.

He found that role when his wife, Pauline, drew his attention to a radio broadcast by Hitler’s second in command, Reich Minister and Air Force Commander Hermann Göring.

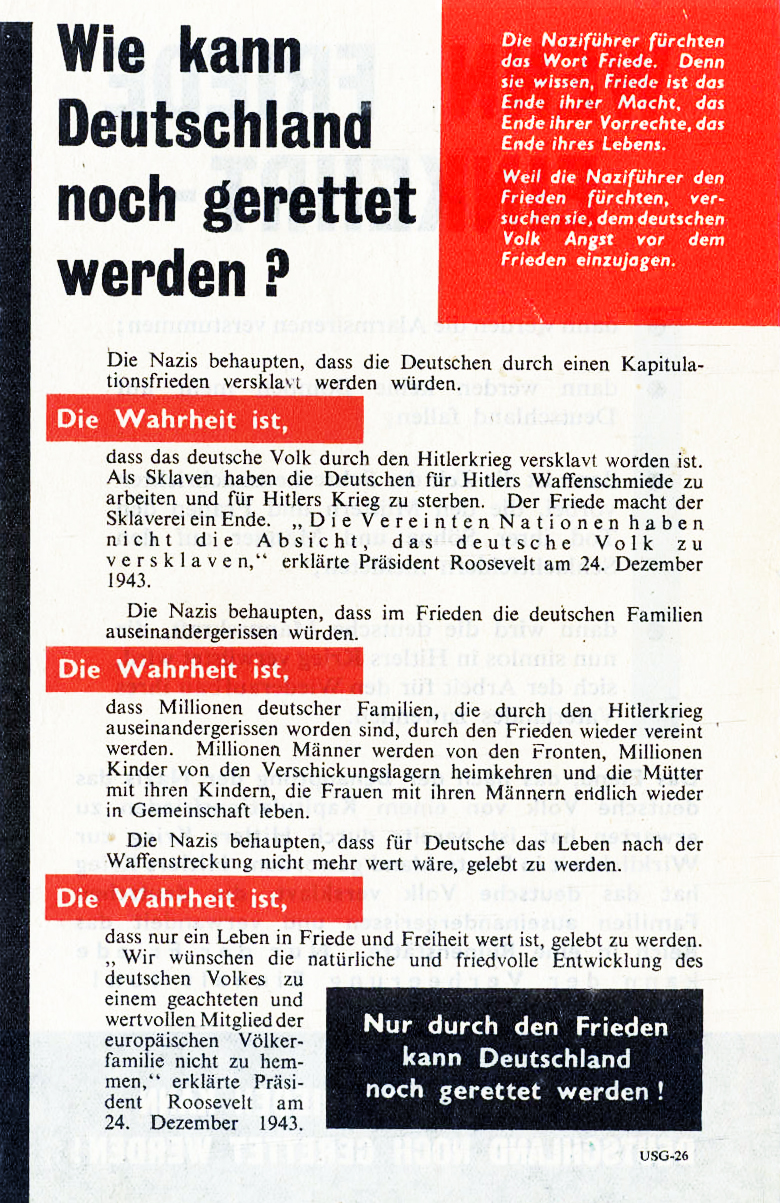

Göring was angry that British pilots were dropping paper leaflets in a direct appeal to the German people to rise up against their Nazi leaders:

“The German people have the right to insist on peace now. We in Britain also wish for peace and are prepared to come to an agreement with a sincerely peaceful German government.”

"It is absurd,” said the indignant Göring, “for our opponent to think some ridiculous pieces of paper can convince a decent German to forget his duty even for one minute." Nevertheless, he announced it was forbidden to read the leaflets.

“The people are astounded by the sight of British airplanes flying casually over Germany,” Kellner wrote, “especially as Reich Minister Göring had pounded into their heads that not a single enemy airplane would ever cross the border.”

When leaflets were dropped in their area, Pauline and Friedrich gathered up handfuls to secretly place in shops and offices. When Friedrich traveled, he left them on the trains and in the waiting rooms—“where wavering Party members would find them," he explained.

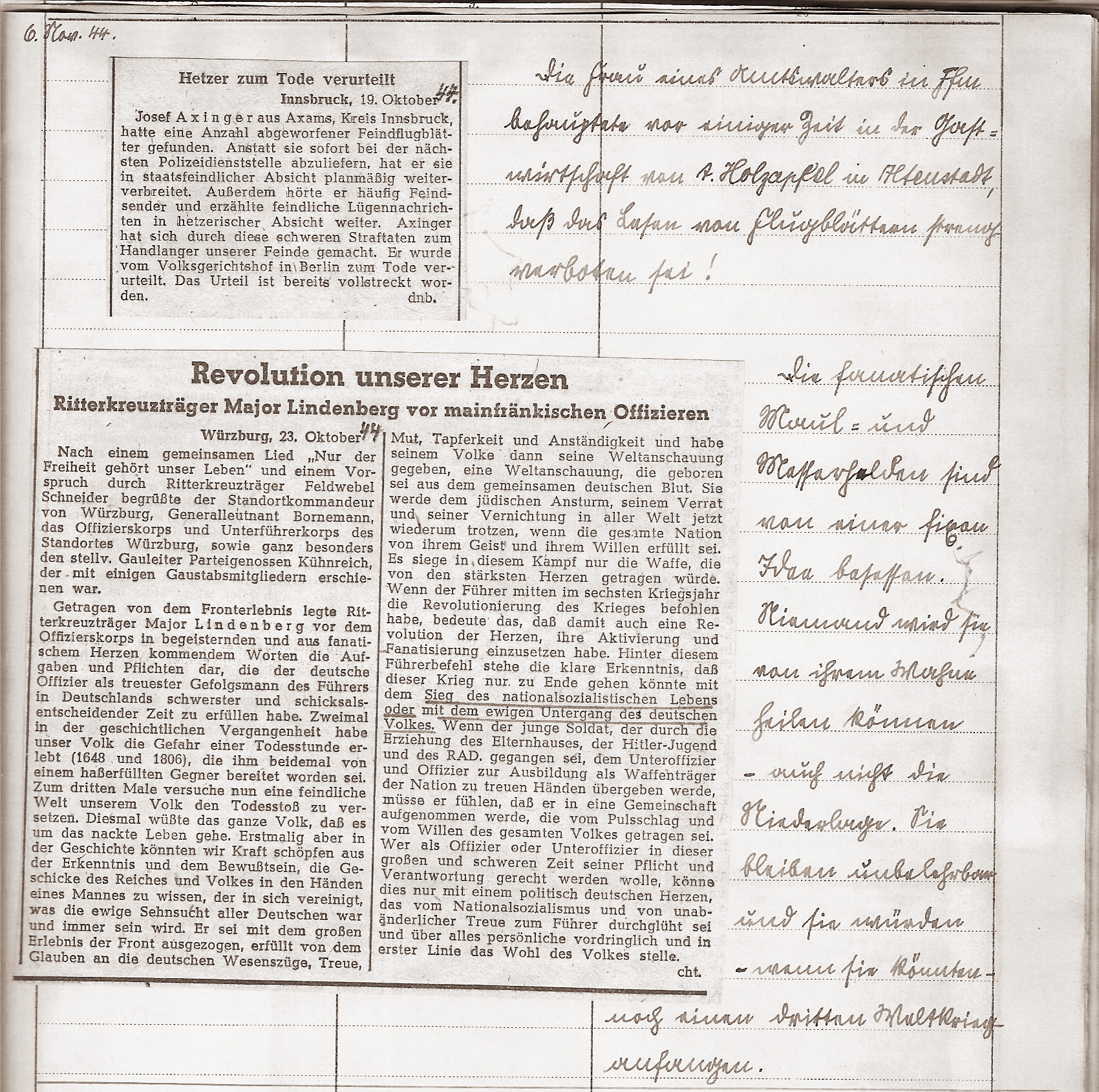

Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels ran stories in the newspapers of people sentenced to years in prison just for reading one--and executed for distributing them.

With a touch of gallows humor, Friedrich pasted some of those news articles in his diary, showing they were aware of the danger.

]Translation: Here is the translation of the smaller newspaper clipping at the top of diary entry 1944 Nov 6:

Provocateur sentenced to death -Innsbruck, October 19, 1944.

Josef Axinger from Amams, near Innsbruck, had found a number of eaflets from Allied airplane raids. Instead of delivering them immediately to the nearest police station, he distributed them with anarchist aims. In addition, he frequently listened to enemy radio broadcasts and continued to tell lies with the purpose of incitement. Through such serious criminal offenses, Axinger made himself our enemies’ accomplice. He was condemned to death by the People’s Court in Berlin.

Here is the translation of the first part of my grandfather's comments, placed to the right of the small newspaper clipping: The wife of an office warden in Frankfurt stated some time ago in August Holzapfel’s restaurant in Altenstadt that reading from leaflets was strictly forbidden!

And here is the rest of my grandfather's comments about the leaflet news clipping, which he wrote further down the page, alongside the larger newspaper clipping.

These fanatical dinner-table heroes are possessed of a fixed idea. Nothing will be able to heal them from their delusion--not eveמ defeat. They remain unteachable, and if they had the ability, they would begin yet a third world war.]

Throughout the war, paper fell from the sky proclaiming the futility of further fighting. Warnings were mixed with offers of friendship to woo the people away from their bellicose leaders:

“You will have nothing to fear after the surrender. Our goal is to provide a peaceful life for all of us.”

“There will be no obstacle to the natural and peaceful development of the German people into a respected and valuable member of the European family of nations.”

Despite such persistence and promises, the Allies were not able to penetrate the shield of Nazi propaganda that controlled the people’s thoughts and feelings.

In August 1944, Friedrich wrote, “One of the women here said her husband had collected numerous leaflets. She proudly described how he followed the law and turned them in without reading a single one. Thus, it continues,” said Friedrich: “a nation of cattle, going along with Hitler to a complete downfall.”

Pauline was not deterred.

“These are generous offers, considering the horrors we inflicted upon our neighbors and the abominations against the Jews. It’s as if Saint Valentine were sending letters of redemption—or at least some kind of partial redemption--from heaven. If we are arrested, that is what I will say in court: These leaflets give our people a chance to repent their roles in this most terrible of wars.”

My grandparents were not caught. Instead, the “leather and steel” Nazi empire collapsed, and its leaders were exposed as savages and punished.

The occupying American forces made Friedrich Kellner the First Councilman of his town, where he helped establish order. He and Pauline enjoyed many more German Carnivals, where Friedrich revived his role as master of ceremonies. Eventually his published diary would reveal the horrors of Nazi rule and serve as a warning lesson to unbridled dictators.

And Valentine's Day became a tradition in Germany, sparked by the presence of so many American, French, and English soldiers.

In 1970, thirty years after Hermann Göring bitterly complained over the radio about leaflets, Friedrich and Pauline Kellner, after fifty-seven years of marriage, passed away within months of each other. When Friedrich's diary eventually was published, the mayor of Mainz designated their graves an Ehrengrab: a Grave of Honor.

My grandparents gave some of the leaflets to me. Every February 14, I look at them and recall a love that survived bombs and rubble, and how my grandmother turned these leaflets of war into greetings from Saint Valentine.

Robert Scott Kellner, a navy veteran, is a retired English professor who taught at the University of Massachusetts and Texas A & M University. He is the grandson of the German justice inspector and diarist Friedrich Kellner and is the editor and translator of My Opposition: The Diary of Friedrich Kellner--A German against the Third Reich, Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom.