As armed groups in Syria and Iraq destroy priceless archaeological sites, European authorities and dealers are on high alert for smaller, looted artifacts put on sale to help finance the jihadists' war.

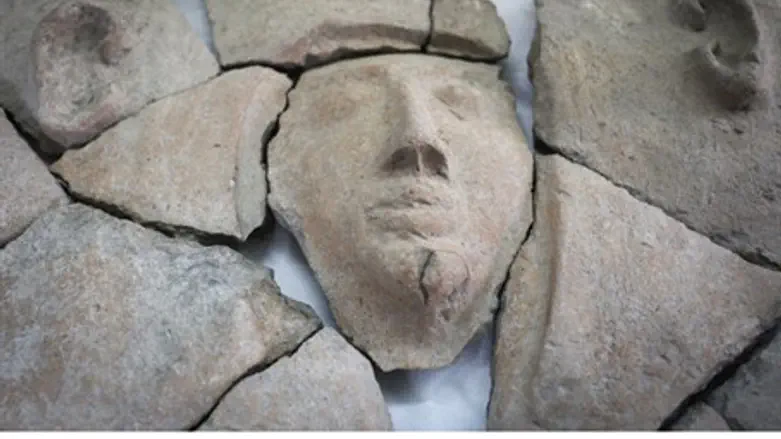

Stolen-art expert Chris Marinello, director of Art Recovery International, said he has been shown photographs of items being offered from Syria that were "clearly looted right out of the ground".

"You could still see dirt on some of these objects," he told AFP.

They included cylinder seals, Roman bottles and vases, although Marinello said it was unclear whether the items were still in Syria, were in transit or had arrived in the key markets of Europe and the United States.

Concerns about looting during the Syrian war have increased following the advance of the Islamic State group through parts of Syria and Iraq, and recent propaganda videos showing their destruction of ancient sites such as Nimrud.

The UN Security Council in February demanded UN states act to stop the trade in cultural property from those two countries, amid warnings that they represented a significant source of funding for the terrorist group.

Experts say it is impossible to put a value on antiquities looted from Syria, which has been home to many civilizations through the millennia, from the Canaanites to the Ottomans.

The London-based International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA) estimates the entire legitimate antiquities market in 2013 was worth between 150 and 200 million euros ($160-215 million).

Marinello said reputable dealers are "being very careful not to touch anything that could remotely be part of this recent wave of looting".

But Hermann Parzinger, an archaeologist and president of the Germany-based Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, said there was an "enormous market" from private buyers.

He warned that the cultural costs were huge, telling AFP: "The context which is so important to reconstruct the history of these civilizations is completely destroyed."

Looted items held back

Italy has proposed that world heritage body UNESCO create a military taskforce to protect cultural sites in war zones, but many experts believe little can be done to stop the current destruction.

Instead, they are forced to wait until the conflict ends and watch in horror as priceless historic sites are destroyed and the spoils gradually

emerge onto the market.

Vernon Rapley, a former head of the art and antiquities squad at London's Metropolitan Police, expects many Syrian items to be held back to avoid flooding the market, as occurred after the US-led invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan.

The looted artifacts were likely to be "hauled up in warehouses either in the country or near the country, and only linked to the art trade in small pieces and at a later stage", he told AFP.

Stephane Thefo, who leads an Interpol unit dedicated to fighting the illegal trafficking of cultural goods, agreed that many items may disappear for years - but insisted that tackling the trade was the best way to combat looting.

The French policeman would like to see tougher national laws on trafficking of cultural goods, something Germany is currently considering.

"We have to act by seeking to narrow markets for the illicit trade, hoping that by curbing the demand, the supply would eventually decrease," Thefo said.

Identifying heritage items

Identifying looted objects is no easy task, however, not least because cultural crime is rarely a police priority.

The law puts the onus on the authorities to prove an item is illegal and a long delay in an artifact being sold, or multiple owners, make it hard to establish provenance.

At a conference at the V&A museum in London this week on the destruction of cultural property in conflict areas in Iraq and Syria, Mali, Libya and Yemen, archaeologists stressed the need for proper inventories of heritage sites.

They noted that objects that have been photographed and digitally catalogued are more likely to be recovered.

Interpol is currently building a database of stolen objects, and James Ede, a London dealer and IADAA board member, urged cultural bodies to share their information with dealers.

"This material will necessarily surface on the open market sooner or later. The challenge therefore is to identify it and where possible to return it when it is safe to do so," he said.