Seventy years after surviving a Nazi death camp and losing several close family members to the gas chambers in German-occupied Poland, 82-year-old Ernst Grube of Munich argues relatives should be allowed to choose their own way of remembering Holocaust victims.

Munich leveled an official ban more than a decade ago on what has become the most personal and popular Holocaust memorial project in Europe today, known as Stolpersteine ("stumbling blocks").

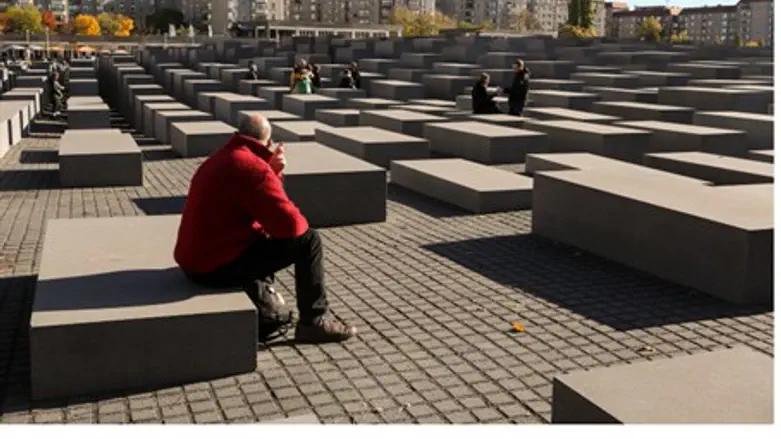

For nearly 20 years, pedestrians have been stumbling across the names of Nazi-era victims on coaster-sized brass plaques embedded in the pavement in front of their last known addresses.

The 50,000th Stolperstein was laid this month, ahead of the 70th anniversary on Tuesday of the liberation of the Auschwitz death camp, and they can now be found in more than 1,000 cities and towns throughout Europe.

Sculptor Gunther Demnig started the project in 1996 to bring the unfathomable dimensions of the Holocaust down to a human scale. Each Stolperstein bears a stark text, with the name of the victim, birthdate, date of deportation and, if known, date and place of death.

However Munich, which was the historical home of the Nazi movement, is the only major German metropolis to outlaw the blocks in public places.

The strongest opposition came from an unexpected place: the leader of Munich's 4,000-strong Jewish community, Charlotte Knobloch, who argued that victims' memories would be desecrated once more when passers-by walked on the plaques.

The ban was so sweeping that two Stolpersteine, for Jewish art dealers Siegfried and Paula Jordan, were dug up again soon after the 2004 decision.

"It was as if my parents were deported a second time," their son, 91-year-old Peter Jordan, wrote to city officials.

Signs of a change?

Grube says he respects Knobloch, who survived the Holocaust in hiding with a Catholic family, but he called her de facto veto of the memorial outdated and unjust.

"I am 82, Frau Knobloch is 82, I was persecuted as a child, Frau Knobloch was persecuted as a child," he said. "Why does her experience count more than mine?"

Grube noted that beyond the six million Jews slaughtered in the Holocaust, groups including resistance members, homosexuals, the disabled, Sinti and Roma and Jehovah's Witnesses were also targeted for extermination. Many of their descendants have now lent their voices to Munich's pro-Stolpersteine campaign.

Knobloch declined an interview but said in a statement sent by email that she maintained her stance, reasoning "people murdered in the Holocaust deserve better than a plaque in the dust, street dirt and even worse filth."

Knobloch suggested "alternatives" including a single memorial with the names of all Munich victims installed at a Nazi party documentation center due to open in April.

The tide, however, may well be turning in favor of the Stolpersteine since the election last year of a new mayor who backs the project, joining proponents including German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Israel's Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial.

An initiative lobbying for Stolpersteine in Munich led by Terry Swartzberg, an energetic American Jew who has lived in Germany for nearly four decades, believes it now has a majority on the city council to overturn the ban as soon as next month.

Swartzberg, 61, said he often receives fervent letters of support from the grandchildren of Holocaust victims in Israel and the United States.

"They say 'we need Stolpersteine, we want to visit the places where our families lived before they were dragged off to Treblinka, to Auschwitz'," he said.

A "lightning rod" for anti-Semitism?

Swartzberg claimed that after deadly attacks on Jews in Paris and Brussels and the troubling rise of a right-wing populist group in the eastern German city of Dresden, the Stolpersteine could serve as a "lightning rod" of anti-Semitism.

"In other words, if Stolpersteine started to be desecrated by neo-Nazis or Muslims we would know that Germany is facing an anti-Semitism issue," he said.

In the meantime, Swartzberg's group has installed more than two dozen Stolpersteine on private property, beyond the reach of city authorities, and has around 300 blocks in a cellar ready to be laid.

Bernhard Purin, director of Munich's eight-year-old Jewish Museum, charged that the city had long lagged behind in owning up to its past.

He said the Stolpersteine represented a "new, democratic" type of memorial, particularly appealing to younger people. "Those who don't approve should perhaps be a little more tolerant," said Purin, 51.

Many in Munich admit the emotional debate around the Stolpersteine has forced the city to address painful questions.

Rudolf Saller, a 59-year-old civil servant, insisted Knobloch's views should prevail given her stature. "She was democratically elected by her community," he said. "The people who are most affected should have their say."

Yet many in Munich seemed to have embraced the project already, said patent office employee Martin Mueller.

"Soon all the survivors will be dead," said Mueller, 48. "We need a way of remembering that stays with us in everyday life."

AFP contributed to this report.