Although it remains to be seen how far we are into the turnaround in the USA from the coronavirus shutdown, there was a sense from the White House briefing on Thursday that it’s where the movement and energy will be. We’re looking forward, not back at this point. The Washington Postcommentary is designed to snark it up and keep the focus on danger and immobility, but the White House has an organized framework for moving forward. And there are governors already working actively to reopen their economies.

At the outset, a few words about the White House’s framework. (The briefing video is at the bottom.) It’s not “a plan,” per se. It’s a set of criteria for safe reopening and a basis for consultation with the states. If you look at the slides outlining that, it’s obvious many of the states must already be looking at the factors listed, such as the ability to test for the virus.

What the White House task force has laid out is what they expect to be consulting with the states about. I’d interpret it as a minimum set of reopening factors, which the states should address, and which the White House and executive agencies will be giving them assistance on, as needed.

It’s a very “CEO” type of communication. “This is what I want to hear from you about. Come back to me with what you need.”

There’s still a long way to go to put the coronavirus crisis behind us. But it’s obvious the American public, especially the millions who have taken it in the economic shorts over the last month, are ready to move on with that. We can’t shelter in place forever. That’s not what we’re here on earth for.

We have to take the moral value of human life, lived to its highest and best, in freedom and with virtue, creativity, joy, and possibility, more serio-usly. One observation of overarching importance before laying out the six interim lessons. The observation is this: we cannot, must not choose to let the virus rule over us as a limiting factor for everything about our future. This virus or any other virus, we must not accept it as a millstone pinning us down and driving us in a circle for the rest of time.

One observation of overarching importance before laying out the six interim lessons. The observation is this: we cannot, must not choose to let the virus rule over us as a limiting factor for everything about our future. This virus or any other virus, we must not accept it as a millstone pinning us down and driving us in a circle for the rest of time.

Well-intentioned professionals in epidemiology, like Dr. Fauci, continue to issue their warnings about how long everything must take, and how we will probably never get back to everything normal for us only six or eight weeks ago. But ultimately, that is not for the epidemiologists to decide. And that’s a good thing.

Our task is not to accommodate ourselves to a threat. Our mission is to defeat the threat and set limits for it, rather than for ourselves. To do that, we have to take the threat seriously. But we have to take the moral value of human life, lived to its highest and best, in freedom and with virtue, creativity, joy, and possibility, more seriously.

With that in mind, here are six lessons to start a dialogue with.

About the virus

1. At the core of the outbreak, the problem has been two factors that produced combustion: the ease of travel around the globe, and the refusal of the national leadership where the virus originated – China – to tell the truth about it in the crucial early weeks.

I am leaving aside, for now, the whole question of whether the COVID-19 virus is naturally occurring or exactly how it may have entered the human population. We haven’t confirmed those points, but we don’t need to, to treat others.

Considering only the two factors mentioned above, we have a robust and vital combined lesson. One aspect of it is that the ability to halt travel at national borders has been indispensable. The other is that relying on the nations to deal faithfully in matters like viral outbreaks is a form of trust that needs some means of accountability and verification.

The balance of nationhood, borders, and robust but regulated travel is a good one, and we need to perfect it further. We don’t have any such means. The World Health Organization proved useless as a broker of information; it merely parroted China’s talking points while the virus was zipping around the globe undetected, in infected but still-asymptomatic hosts.

We don’t have any such means. The World Health Organization proved useless as a broker of information; it merely parroted China’s talking points while the virus was zipping around the globe undetected, in infected but still-asymptomatic hosts.

The remedy here is not to shut down travel in some dramatic and permanent fashion. It most certainly is not to weaken or eliminate national borders. National borders and the power behind them protected millions of people from communist predation in the last century; we have just seen them protect millions from infection by a highly contagious virus in this one. The balance of nationhood, borders, and robust but regulated travel is a good one, and we need to perfect it further.

What to do about compelling better faith from a national leadership like China’s is a more difficult problem to scope. Up to now, President Trump has elected not to “go there,” but it’s virtually certain that at some point, we’ll have to. I doubt we’ll try to push anything through the U.N., at least while Trump is in office. National intelligence efforts targeting a nation like China; the threat of ejection from global bodies and forums; sanctions – these seem to be the likely mechanisms for reaching a “trust but verify” modus vivendi.

Consultation among the nations is a positive good, but it needs teeth and accountability. We need to reconsider multilateralism and ponder the benefits of nationalism-in-concert, with the emphasis on nations getting together, as opposed to “global” bodies purporting to prioritize for everyone.

2. We need to think harder and with more foresight about dealing with epidemic disease. I am not convinced that the only way to deal effectively with COVID-19 was to shut down entire national economies to the catastrophic level we chose. This is partly because of the virus itself, which early on demonstrated that its fatality rate was strongly skewed to people over 65.

It is merely not logically necessary to freeze all the people under age 65 in place to give the people over 65 the best chance of survival. We absolutely want to save the lives of our beloved elders, but doing so almost certainly didn’t require declaring vast chunks of our national economies “non-essential.”

It is also fair and necessary to make this point: state of the art in any endeavor, including treating and curing disease, is always a transient and evolving thing. President Trump has been right to praise and recognize the many ways in which industry and the research community have stepped up. But for me, there has been a nagging sense that we’ve been doing what the military has always slapped itself afterward for doing: fighting the last war instead of the current one.

Does it really require a minimum of 18 months to develop a vaccine? Is a “vaccine,” as we understand it today, a measure whose features cannot change to become more effective or convenient? How about detection? Can we speed up our adaptation and invention to do that? What do we need to think about differently in terms of discovery and invention, to get ahead of this problem in that way as opposed to heaping rearward-looking regulatory burdens on humans?

If we start out by dismissing these possibilities, we are guaranteeing ourselves a future of being whipsawed by the next contagious virus, and the next, and the next. Only by asking these and similar questions with an open mind, and pursuing with determination answers that are gratifying for the value of good and abundant human life, will we actually get beyond the dynamic of being warned by epidemiologists that there’s no telling if we’ll ever be able to attend NBA games with 20,000 screaming fans again.

Wrong answer. But we have to ask better questions to get the right ones.

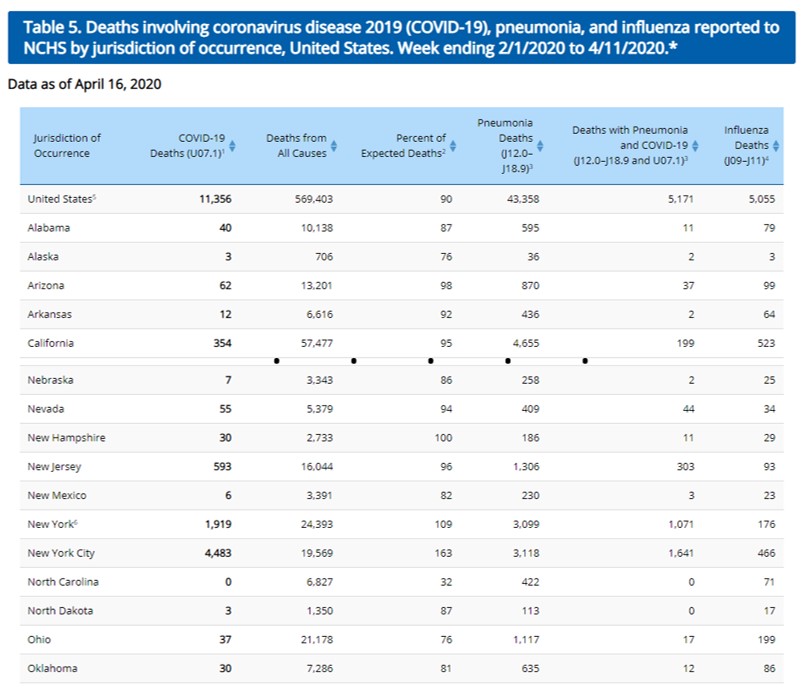

3. This is a brief but critical point. New York City is an outlier. It is not the standard by which we should decide how the entire nation, or indeed how most of the world, should be shut down to arrest the spread of a virus.

This account of infection and deaths from COVID-19 is a vivid visual.

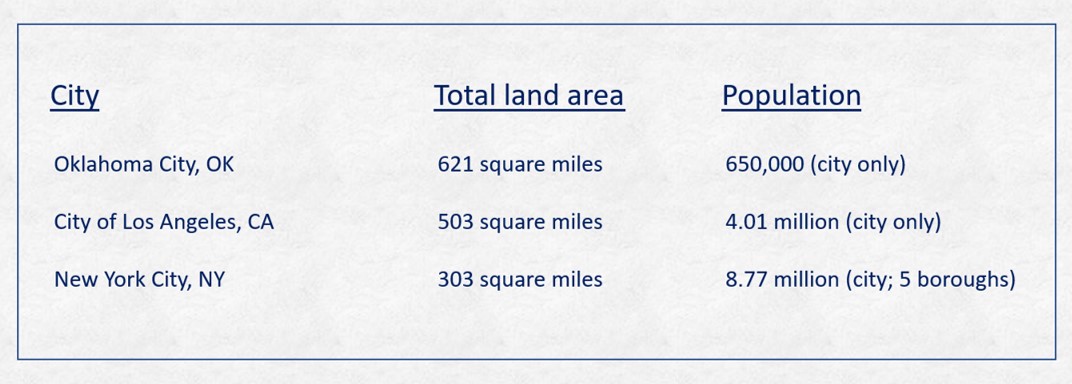

It simply is not necessary to plan or execute as if there is anywhere else in the United States, where so many people are crammed into such a small area. A comparison:

The needs of New York City, as opposed to other locations, are indeed somewhat ironic. Nowhere would it have been as useful as in NYC to shut down mass transit to inhibit the spread of the virus. But nowhere is it as necessary as in NYC to keep mass transit going to have the most essential services: hospitals, emergency workers, retail food, household items, and prescription drugs, public sanitation, power, water.

If anything, New York City shows us that piling people on top of each other in higher urban concentrations than what we have now is a terrible idea, if we want to be less susceptible to a contagious disease. The more spread out people are, the less readily an infectious virus is likely to spread.

About the broader reaction to the virus

In the coming days, we should have robust and wide-ranging discussions on these topics. Here I will only attempt to outline them. I’m sure this list isn’t comprehensive, but the issues are massive ones, striking at the heart and soul of human organization. The coronavirus will compel us to think and talk about them, and that’s a good thing. Instead of addressing them over the last four-plus years, we’ve been yelling at each other about Donald Trump. It’s time we focused on what actually divides us.

4. The COVID-19 virus has shown us in stark terms how anxious some among us is to take advantage of a crisis. In some states, governors and mayors have insisted on levels of control over the public’s behavior that have no reasonable purpose (e.g., prohibiting people in the entire state of Michigan from walking across their yards to visit their neighbors, or banning people in Kentucky from attending a parking-lot church service in which everyone sits in his car with the windows rolled up).

But taking advantage of the crisis goes well beyond imposing unreasonable limits on daily life. In Congress, the Democrats in both houses have tried to completely transform how Americans vote as part of the “stimulus/relief” measures for dealing with the coronavirus (e.g., here and here). That is not only precipitate and wrong-headed; it’s unconstitutional. The states administer voting and should continue to do so without federal mandates (i.e., for universal by-mail voting) usurping their prerogatives.

We have also seen the “green” lobby step forward promptly with polished proposals to take advantage of the disastrous, self-imposed collapse of our economy to implement “green” agenda measures. That doing so would completely alter people’s future expectations, requiring everyone to live in a very different way, is basically acknowledged, if not highlighted.

What is not so well framed is the point that we actually have no idea the full scope of the consequences we’d be inviting on ourselves if we were to pursue such an agenda. But we can foresee things that would cause a whole lot of people to fight now rather than have to give up on life later, due to the ideological mandates levied by others.

A great deal of managerialism and mandate-levying has come swarming out of the woodwork in the virus crisis (there are far too many examples to list here; just one would be the steep, discouraging set of criteria California’s Governor Newsom wants the state to meet before opening its economy up again. One of them is the ability to require and administer blood tests before people can go back to work – apparently on an open-ended basis for the foreseeable future).

This virus episode has clarified that we are not all pulling for the same thing in America. There are millions of people who do not see these agenda items as necessary, much less as elements of a desirable future. Not only that, the mindset behind them is one there is no compromising with. The government is either in thrall to it, or not, and if it is in thrall, its reach and behavior are unacceptable.

5. The COVID-19 crisis is a watershed on the most essential human levels because it has caused the relationship between man and the state to surge to the fore. This is the topic one could spend the most time on, but I will present only one dimension of it here.

The COVID-19 crisis is a watershed on the most essential human levels because it has caused the relationship between man and the state to surge to the fore.  It’s what I think of as the “lowest common denominator” theory of “government control” (for want of a better expression). An excellent reference point for this is how anti-gun activists seek to have government treat competent, law-abiding citizens when it comes to guns: that is as if they are no more trustworthy than the least trustworthy among us. The activists want to constrain and restrain everyone as if we are all mentally ill, hardened criminals, senile, or too juvenile to be trusted with any responsibility.

It’s what I think of as the “lowest common denominator” theory of “government control” (for want of a better expression). An excellent reference point for this is how anti-gun activists seek to have government treat competent, law-abiding citizens when it comes to guns: that is as if they are no more trustworthy than the least trustworthy among us. The activists want to constrain and restrain everyone as if we are all mentally ill, hardened criminals, senile, or too juvenile to be trusted with any responsibility.

In the view of the anti-gun activists, someone is always armed, but it’s always agents of the state. No freedom of any kind can ultimately survive this imbalance, which is why America’s Founders put the Second Amendment into the Constitution.

In the current crisis, a similar pattern has been public authorities imposing restrictions on everyone that are really only necessary for the most vulnerable parts of the population. Although it would have been stupid to encourage healthier, less-vulnerable people to contract the virus to develop immunity, it was dumb equally to issue directives as if everyone were over 65.

It is also actively stupid, especially when so much of the country is seeing hospitals nowhere near capacity (because tending to non-urgent medical needs has been deemed non-essential), to insist that continuing to restrict movement on a lowest-common-denominator-of-vulnerability basis is the only option. At some point, the reality has to set in that we must have the young and robust working if everyone is to have something to eat. (Not to mention having toilet paper and paper towels.)

But the crucial point here is not the one about our specific, current crisis. It’s the point that there are decisions the state should not be in a position to make for us on a prophylactic basis – even though viruses, like guns, are lethal things. The state is just other people, chartered to carry a firearm and enforce mandates. It’s not a magical force that knows more than we do or acts more virtuously or knowledgeably.

In an age when it is literally possible to notify everyone immediately that he is required to stay indoors, and police are increasingly empowered to act as if we are all criminals waiting to happen. Our social media profiles tell them just when that will be, it isn’t good enough to leave this matter unaddressed. The relationship of the state to us is already changing, in ways that need not be inevitable, but will require decisive action to intercept. The virus has thrown that into vivid relief.

6. The final interim lesson is one we will learn much more about in the coming days. It is that the longstanding federal-state dynamic in the U.S. is under increasing strain – and this isn’t even about Trump and a list of Democratic governors. It’s about a development that may have been inevitable, to some extent, but that could pose a significant threat to our future as a nation.

The lens we see it through is the regional alliances governors have formed in the last week to consult on reopening their economies. This may be too new an idea to go over easily with some readers, but there is very little chance of being wrong in this assessment: the pattern bodes ill for our national unity and the proper powers of the federal government.

I wrote earlier that no such effort is ever agenda-free or a mere seminar experiment in government organization. Some of the things these alliances could do are amass bargaining power versus the federal executive, develop lists of demands, and generate blocs in the Senate and House that effectively override the traditional lines at the national level of party and principle.

The representatives of the seven Northeastern states led by New York don’t all vote the same way in Congress. The same is true of the Pacific Coast states and the Midwestern states. But if there is momentum for an interstate brand of “regionalism” – until now, a phenomenon urged by activists at the city-county level – these alliances could, in fact, rewrite one of our most basic political realities in Washington, D.C.: the check conferred by the U.S. Constitution, especially in the Senate, of more-rural areas on mass urban population centers.

In blunt terms: as the map stands today, this move – given the states that have jumped on it – could hardly be better designed to gain a blue-counties power position over America’s red counties.

The regional state alliances aren’t likely to go away when the virus crisis can no longer be their purpose. That is especially the case if they rack up any political victories that can be attributed to their existence and use. As Rush Limbaugh likes to say, Don’t doubt me on this. This is something to be concerned about.

White House briefing

In the video, the gist of the current situation and framework outline for reopening starts in minute 19:00, with Vice President Pence briefing.

The writer is a retired Naval Intelligence officer who lives in Southern California and is Editor-at-Large for Liberty Unyielding. Her articles have also appeared at Hot Air, Commentary’s Contentions, Patheos, The Daily Caller, The Lid, The Jewish Press, and The Weekly Standard.