Last Shabbat, in Parashat Terumah, we read G-d’s instructions to Moshe, atop Mount Sinai, how to build the Mishkan (Sanctuary). This week, Parashat Tetzaveh continues with G-d’s instructions to him – what to command to the Kohanim (Priests) who were to minister in the Mishkan, the priestly garments they were to wear there, and the rituals that they were to perform there.

And yet, even though Parashat Tetzaveh continues G-d’s monologue to Moshe, the name of Moshe is nowhere mentioned.

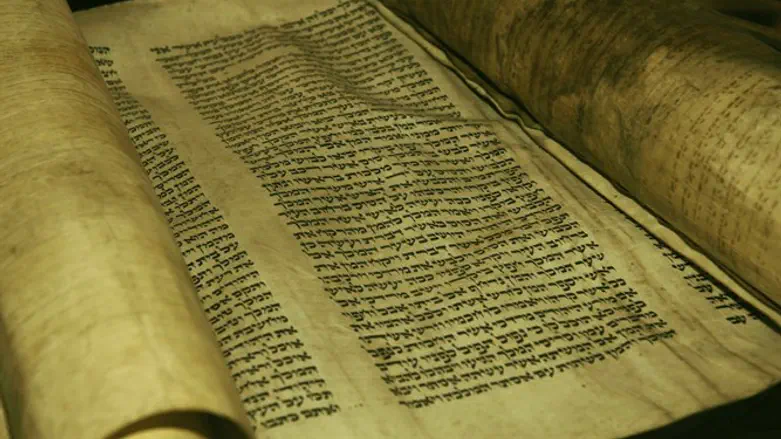

This would appear to be a deliberate decision of the Rabbis who divided up the Torah into the 54 parashot (with which we are so familiar today) in the late Second Temple period. Parashat Tetzaveh finishes with Exodus 30:10, which is the end of a paragraph; it could easily have continued for one more paragraph, concluding with 30:15, and Moshe’s name would thus have appeared in this parashah.

So why did the Rabbis [deliberately?] divide up the Torah such that Moshe’s name would nowhere appear in Parashat Tetzaveh?

The Vilna Ga’on (Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman Kremer, 1720-1797) noted that Parashat Tetzaveh always falls around 7th Adar, the date that Moshe died [1]. Thus Moshe’s name is missing in this parashah, paralleling how Moshe was missing in this world at this time of year.

The Ba’al ha-Turim (Rabbi Ya’akov ben Asher, Germany and Spain, c.1275-1343) has a very different explanation, which he gives in his very first comment on Parashat Tetzaveh: “Moshe is not mentioned at all in this parashah, which is unique in the entire Chumash – from the time that Moshe was born, there isn’t a single parashah which doesn’t mention him. The reason is that he said ‘Erase me now from Your Book’ (Exodus 32:32), and as the Talmud says, ‘The curse of a Sage comes to pass, even if it is made on condition and the condition does not come to pass’ (Makkot 11a)”.

The Ba’al ha-Turim’s comment gives us an immensely valuable insight – far deeper than his brief, terse words indicate at first glance.

Following the sin of the golden calf, G-d threatened to destroy the entire Jewish nation: “I have seen this nation, and behold – it is a stiff-necked nation. So now leave Me be, My fury will flare up against them and I will exterminate them, and I will make you into a great nation” (Exodus 32:9-10).

Moshe pleaded with G-d to spare His nation, to which G-d acceded, and Moshe then left G-d and descended Mount Sinai back to the people.

Having led his fellow-Levites in killing some 3,000 of the golden calf worshippers (v. 28), Moshe returned to G-d the next day with an additional demand. It was not enough for Moshe for G-d had agreed not to exterminate the Children of Israel – he wanted Him to forgive their sin entirely: “So now, if You will forgive their sin – ! And if not, then erase me now from Your Book which You have written” (v. 32).

The Targum Yonatan paraphrases: “So now, if You will forgive their sin, then forgive! And if not, then erase me now by justice from within the Book of Tzaddikim which You have written in my name”.

(G-d wrote the Torah, but it is very frequently called “the Torah of Moshe” – Joshua 8:31, 23:6, 1 Kings 2:3, 2 Kings 14:6, Malachi 3:22, Daniel 9:11, Ezra 7:6, 2 Chronicles 23:18, and many other places).

Rashi comments: “‘From Your Book’ – from all the Torah entirely, so that no one will say of me that I wasn’t worthy of asking for mercy for them”.

According to many sources, particularly in the Kabbalah, Moshe was the gilgul (the reincarnation) of Noah [2].

There is much that Noah and Moshe share: both were cast into an ark (both Noah’s ark and the basket in which Moshe floated on the River Nile are called תֵּבָה, teiva, in Hebrew); both arks were waterproofed with pitch (Genesis 6:14, Exodus 2:3); in Noah’s flood the rain poured down for forty days and forty nights while G-d protected him, and Moshe spent forty days and forty nights atop Mount Sinai; and both Noah and Moshe were the conduits through which G-d established His Covenants – Noah the Covenant with all humanity for all generations and with all living creatures (Genesis 9:8-17), Moshe the Covenant with the Jewish nation.

Whether we take the concept of gilgul literally or metaphorically, Moshe rectified Noah’s greatest failing. When G-d told Noah of His intention to destroy the entire world by flood, Noah remained silent instead of protesting: from Noah’s birth until after the Flood, the Torah does not record him as having said even a single word. As a consequence, he did not succeed in saving a single human outside of his own immediate family.

In stark contrast, when G-d told Moshe of His intention to destroy the entire Jewish nation, Moshe immediately protested vociferously, and defended the nation with his very life.

Thus the Midrash records Rabbi Berechiah’s statement: “Moshe was more beloved than Noah. Noah went from being called ‘a righteous man’ (Genesis 6:9) to being called ‘a man of the earth’ (9:20); whereas Moshe went from being called ‘an Egyptian man’ (Exodus 2:19) to being called ‘the man of G-d’ (Deuteronomy 33:1)” (Bereishit Rabbah 36:3)

The great Kabbalist the ARIza”l (Rabbi Yitzchak ben Shlomo Luria, Israel, 1534-1572), noted that the word מְחֵנִי (“erase me”), with which Moshe defended Israel, has same letters as מֵי נֹחַ (“the waters of Noah”, the standard appellation for the waters of the Flood). Noah did not pray and intercede for his generation, so Moshe’s tikkun was his intercession with G-d: “If You will forgive their sin – ! And if not, then מְחֵנִי, erase me now from Your Book” (Exodus 32:32).

This year, as in almost all non-leap years, Parashat Tetzaveh is also Shabbat Zachor, the Shabbat of Remembrance, the Shabbat which immediately precedes Purim. (In the last century, there have been only five non-leap years in which Shabbat Zachor did not coincide with Parashat Tetzaveh.) On Shabbat Zachor, the Maftir, instead of being a repeat of the final several verses of the parashah, is instead an entirely different reading:

“Remember what Amalek did to you when you were on your way out of Egypt – how he happened upon you on the way and attacked you from behind, all those who were straggling behind you, when you were tired and weary and he did not fear G-d. So it will be, when Hashem your G-d will give you respite from all your enemies surrounding you in the Land which Hashem your G-d gives you as an inheritance to inherit – erase the very memory of Amalek from beneath the Heavens; do not forget” (Deuteronomy 25:17-19).

This Maftir-reading is of course eminently appropriate for the Shabbat immediately preceding Purim: Haman, who endeavoured to exterminate all the Jews throughout the Persian Empire (which meant almost all the Jews in the world at the time), was descended from Amalek.

Several years ago (/Articles/Article.aspx/6959#.VO47-Y5Cm-1) we examined why Amalek is unique. Other nations which attacked and persecuted us had reasons: Egypt wanted cheap slave labour, Ammon and Moab fought against us to protect their own territorial integrity, the Canaanites were fighting for what they believed to be their homes, Babylon was building an empire.

Amalek, by contrast, had not even an unjustified excuse. He attacked us in the desert, facing no threat – not even an imaginary threat – to his nation or his territory. His attack on us was pure hatred for Israel and – more importantly – hatred for the holiness that Israel represents.

Nevertheless, the command to exterminate Amalek seems unduly harsh and vengeful. However unjustified his attack was, it was after all no more than a brief desert skirmish. Is it fair to condemn an entire nation to extermination for eternity because of what their ancestors had done?

Some 430 years after Amalek’s attack, the prophet Samuel told King Saul, the first king of Israel: “Hashem has sent me to anoint you as king…over Israel… Thus said Hashem, Lord of Legions: I yet remember what Amalek did to Israel…on his way up out of Egypt; now go, smite Amalek, destroy everything that he has, and have no mercy upon him; kill man and woman, infant and suckling, ox and sheep, camel and donkey” (1 Samuel 15:1-3, with which the Haftarah for Shabbat Zachor begins).

And our war against Amalek continues for generation after generation.

The question remains: where is the justice in this?

Maybe Parashat Tetzaveh provides us with an answer. Moshe is central to Parashat Tetzaveh, the entire parashah records G-d’s words to him – yet his name is never mentioned. But though Moshe is concealed, he has not vanished, he will reappear in next week’s parashah, Ki Tissa, undiminished, unchanged, still with the same verve and the same task as ever.

And so too, for long periods of history, Amalek is concealed. For generations, even for centuries, Amalek disappears. Thus was it in the days of King Saul. Amalek appeared to have been defeated, reduced to a few pitiful remnants. How could that nation still pose a menace to Israel – Israel, which within a generation would become the region’s unchallenged and unchallengeable superpower?!

Yet half a millennium later, when Israel was weak, scattered in exile, ruled by Persia – suddenly Amalek popped up again, this time in the guise of Haman, undiminished, unchanged, still with the same verve and the same task as ever.

Concealed is not the same as non-existent. Sometimes, that which is concealed is the most central. Moshe is concealed from Parashat Tetzaveh – yet the entire parashah records G-d’s words to him. The 7th of Adar (Thursday, two days before Shabbat Parashat Tetzaveh) marks Moshe’s death, the day he left this world – yet Moshe remains and will always remain our greatest-ever leader and teacher.

And even when Amalek seems to have disappeared, he and his evil remain very real in the world. After almost a thousand years had elapsed from Amalek’s first attack, and almost 500 years since they had been defeated by King Saul, the Jews must have been confident that Amalek was consigned to the distant past.

But suddenly he popped up again in Persia, still embarked on his primordial mission of exterminating the Jews. So no – G-d’s command to eradicate Amalek is not harsh or vengeful. It is as appropriate as it ever was, even though today we have no way of identifying Amalek (see Yoma 54a).

This coming Thursday we will celebrate Purim (except for Jerusalem, where we will celebrate Shushan Purim on Friday), remembering Haman’s defeat.

The Megillat Esther never once mentions G-d; He is concealed – yet G-d controls the entire sequence of events. G-d, concealed in the seemingly natural way of the world, is at the centre, controlling all.

The concealed and hidden factor, which in fact is the single most central element, which G-d gives us the discernment to perceive if we but apply the intelligence that G-d has granted us – this is the story of Parashat Tetzaveh, of Moshe’s death, of Amalek, of Shabbat Zachor, and of Purim.

Endnotes

[1] Though the Torah does not specify the date that Moshe died, the Talmud (Sotah 12b, Kiddushin 38a) and the Midrash (Mechilta de-Rabbi Yishma’el, Beshallach, Massechta de-Vayasa 5 and Tanhuma, Va-et’chanan 6) derive the date from the Tanach. When Moshe died, “the Children of Israel mourned him…for thirty days” (Deuteronomy 34:8). Following this 30-day period of mourning, Joshua told the nation that in another three days they would cross the River Jordan into Israel (Joshua 1:10-11), and they crossed the River Jordan on the 10th of Nissan (Joshua 4:19). Thirty-three days before the 10th of Nissan was the 7th of Adar.

[2] See for example Tikkunei ha-Zohar 117a and Sha’ar ha-Gilgulim (Gate of Reincarnations) by Rabbi Chaim Vital. Hence the Hassidic master Rebbe Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev (1740-1809) wrote, in Kedushat Levi on Parashat Noach, that “Moshe is the tikkun (the rectification) for the soul of Noah”.