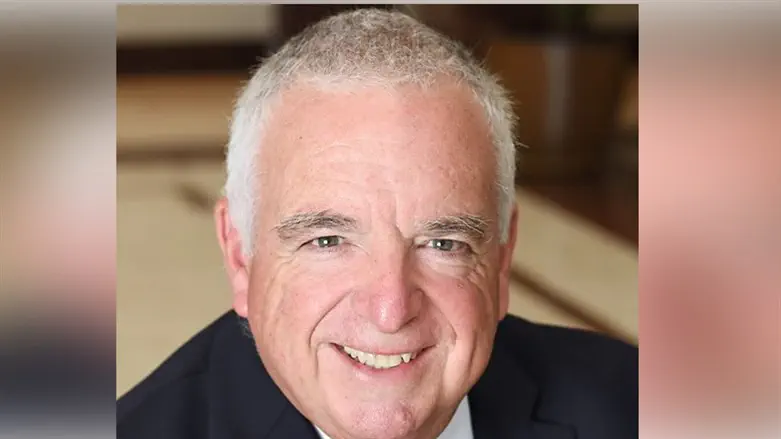

Stephen M. Flatowis President of the Religious Zionists of America (RZA) He is the father of Alisa Flatow, who was murdered in an Iranian-sponsored Palestinian terrorist attack in 1995 and the author of A Father’s Story: My Fight for Justice Against Iranian Terror. Note: The RZA is not affiliated with any American or Israeli political party.

It’s 29 years since my daughter Alisa was murdered in cold blood in an Iranian-funded Islamic Jihad/Hamas bus bombing near the then-existing Israeli community of Kfar Darom on April 9, 1995. Much has happened since then and much has stayed the same.

You can ask any parent who has lost a child, one never forgets the time and circumstances of his child’s death whether from a highway accident, a drug overdose, a suicide, cancer or a terror attack. It is so unnatural for a parent to bury a child that even our most learned rabbis cannot find the right words to take away the shock and pain of loss. Saying your daughter died “al Kiddush hashem” as have millions of Jews before her and thousands after her helps, but it’s not the be all and end all answer. One size does not fit all. And God does not always give people problems they can manage.

While I appreciated the advice and words of comfort since that dreadful day and during the years following, I prefer to look at what has transpired within our family to find my comfort.

My wife Rosalyn and I have been blessed with children who live productive lives in New Jersey and Jerusalem. With them, there are 16 grandchildren; nine girls and seven boys. Our oldest grandchild Michal, the first of four to be named after Alisa, is married and living in Jerusalem for a year with her husband Aryeh. They recently gave us our first great-grandchild, Avigayil.

When people talk about their family’s roots, called yichus in Yiddish, they tend to look backwards. In America, some can trace their ancestry back to the passengers on the Mayflower. American Sephardim can go back far, too, to the early 17th century when families booted from Spain and Portugal during the Inquisition traveled via Brazil to the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. The same can be said of the members of “Our Crowd,” German Jewish emigrants who went on to amass great wealth in New York City’s business world. Their family stories are well documented.

We whose roots go back to Poland and Russia don’t have that documentation down pat, at least for my family.

First, our name in the alter heim was not Flatow. It was Platzik; at least that’s what it says on my great grandfather’s tombstone. My grandfather’s “certificate of arrival” filed with the Immigration and Naturalization Service has his name as Plazik. But, lo and behold, the name Flatow suddenly appears on his Declaration of Intention to apply for citizenship 6 years after his arrival. The only consistent item in my search for the family name is the consistent naming of Kikol, located a few miles from Warsaw, as the family’s hometown.

Religious observance among my relatives was almost non-existent. Sure, my grandmother and mother cooked kosher, and we had our raucous family Seders each year. With 6 sets of aunts and uncles, and a bunch of first cousins, how could the Seder not be raucous? Starting afternoon Hebrew school at the age of 7, I was the one who stood at my seat at the “kid’s table” (remember those?) and sang the fier kashas” at everyone’s request.

Moving to Monsey, NY, in 1960 before it became the Monsey we know today, any connection to observance we had before dissipated. We had never seen supermarkets like the Grand Union in Monsey, or the Daitch-Shopwell in Spring Valley and the shopping experience must have overwhelmed my mother because, while she ordered meat from the kosher butchers, she also brought ham into the house. But, heaven forbid, we never had milk with meat!

I look back on those years before marriage and children and wonder why I’m not more mixed-up than I am. But allow me to let you in on a secret, it took a four-year-old child, Alisa, to change a family around from the path we, like so many American Jews, were walking upon, a three-day-a-year Judaism and all the damage that has done to traditional Jewish life.

It was Alisa who set us on the path of observance by her insistence on going to a yeshiva instead of the neighborhood public school. She brought us along on the road to observance not by making demands, but by example. As she was learning in yeshiva, I was learning with her. She could bentsch before I could. She would stand beside me at the Shabbat table and sing the entire birkat hamazon and before long I knew the tune, too. When it came to her Hebrew studies, she was pretty much on her own as her parents’ afternoon Hebrew school educations didn’t give us the knowledge we needed. Sure, we could help her find words in the Shiloh dictionary, but that was it.

Her siblings followed in her footsteps, and I learned from them, too.

Now, please do not interpret this as being a Baal teshuva story; it took me and my kids a long time to get things the way they should be. So, my daughters and son know what Pizza Hut is, and had fancy dinners at a very nice Italian restaurant near our home; after all, “we’re having fish and pasta, so that’s ok, right?”

I often wonder what my sons-in-law think when they hear stories about the old days, BR, before religion. But it’s all good. My daughters cover their hair and do all the other things that FFB, frum from birth, women do. And my grandkids, they know nothing other than a religious lifestyle.

When someone brings up a chumra (a stringency), I often shake my head. As I was complaining to one of my daughters about how frustrating it is when a granddaughter tells you she can’t have your BBQ because she doesn’t “hold by that hecksher (kashrut supervision)”, the answer was “ blame Alisa.”

We say that with a smile and a chuckle, because, well, it’s true; but we wouldn’t want to live any other way.

The yahrzeit of Chana Michal bat Shmuel Mordechai v’Rashky is 10 Nisan.