In Israel few synagogues have official rabbis, or professional cantors or formal choirs. Services are mostly conducted by congregants, though they can’t always hold a tune. Every Jew thinks he is a cantor – except that today he has a cold.

In my shul the cantor and I worked together, lived in the same building, and he and his wife treated our family like their own grandchildren. I didn’t sing and he didn’t preach, though at times I led services. I couldn’t give the choir a lead in; they wanted to lead me out.

From the time of Moshe Rabbenu the rabbis were expected to be sages and judges. In time, the rabbi became a Jewish version of the Christian pastor, but in recent years the learning and teaching role has re-emerged.

Chazanim (cantors) weren’t originally officiants but overseers and supervisors. They didn’t all have good voices: some didn’t pray but bray. Only when officiating by heart became too hard for lay people did the chazan become a professional singer.

The task of the chazan is to be "sh'liach tzibbur", "the agent of the community", since he does not pray for the congregation but gathers their prayers before the Almighty. From "sh-tz" (the initials of "sh'liach tzibbur") derived the Jewish surname of Schatz.

A cantor must be pious, learned, of good reputation, upright, modest, possessed of a good voice, acceptable to the congregation: preferably a mature person who is married and has children… and worries.

Controlling the choristers was never easy. Choirs often sang from a gallery above the Ark; in one shul the choirmaster leant back and his kippah fell off onto the "ner tamid" (the Eternal Light), prompting the remark, "What a bright spark he is!"

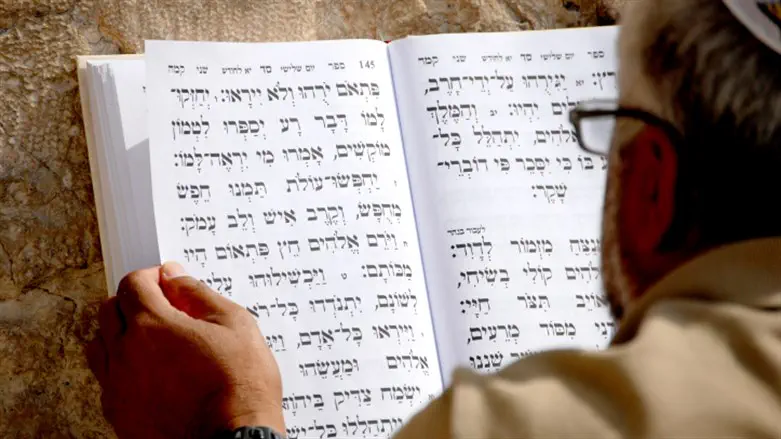

In many congregations there is a cantor’s meditation on his role. Sung before the High Holyday Musaf, it comes from medieval Europe. We don’t know who wrote it. It is said quietly, with the congregation eavesdropping. The first word, "Hinneni", is suggested by Abraham’s response to God’s call in Genesis 22.

When called to duty, the cantor wants to shrink back, but knowing that the rabbis say, "Where there are no men, you be a man!" (Avot 2:5), he summons the courage to say, "Here I am!" and to pray, "O God, make me worthy of my task!" He says:

In love, truth and peace, let no defect mar my prayer.

May it be Your will, O Lord, God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob,

Great, mighty and awesome God, God most high, eternal,

That all the angels that carry our prayers

Wing my prayer to Your glorious throne, and offer it to You

In the merit of all the righteous, pious, honest and upright ones,

And for the glory of Your great, mighty and awesome Name,

For You hear the prayer of Your people Israel in mercy.

Blessed are You, O Lord, who hearkens to prayer.

ON HOLY GROUND

God said to Moses, "Remove your shoes, for the place where you stand is holy ground" (Exodus 3:50).

The place where we stand on Rosh Hashanah is also holy ground. We do not have to remove our shoes (though we do on Yom Kippur), but what we have to put aside are the concerns that fill our minds throughout the rest of the year.

These concerns which have no place on Rosh Hashanah are jealousy, rivalry, egotism and selfishness, attitudes which put down other people and leave no room for them, especially if their race, religion, politics and possessions are different from mine.

I had a friend who used to say that in God’s eyes we were all the same because "your grandmother and mine dried their washing under the same sun".

On holy ground there is tolerance. But somehow there is also intolerance; Professor Alexander Altmann said, "There are both tolerance and intolerance in the Jewish tradition".

The tolerance is not that of a polytheistic society when one man’s god is as good as another’s. It is the kind of tolerance which is "a radical innovation in the history of religion", a tolerance which gives everyone a right, a dignity, an identity, all living their lives under the same sun.

The intolerance is of ideas of superiority that say, "I have every right to be myself… but if you want the same right for yourself, I have the right to kill you so that you do not pollute the earth".

On the holy ground of Rosh Hashanah the Jew says, "Surely we can smile at each other and enjoy the same sun."

THE DOUBTER’S PRAYER

Some people are uncertain about whether they believe in God, so they say they can’t be asked to come to synagogue and pray.

We see their point, but feeling unable to pray is no argument against prayer. It is precisely in moments of doubt that worship is relevant and important.

What sort of prayer should the doubter say?

Two possibilities. One, "God, I’m not sure I believe in You but please help me one way or the other. If deep down I really do really believe in You, please assure me of Your existence; if deep down I am still a doubter, please assure me that You wish me well."

Further, you could tell God, "I’m not sure You are there, but if You are, this is what I would like to say to You…"

Both prayers give God the benefit of the doubt and leave your intellect intact because:.

TESHUVAH IS FOR EVERYONE

No moment in Jewish history was as breathtaking as the revelation at Sinai. At that moment a slave rabble became a people of prophets. No one was unmoved and untouched by the experience.

What brought them to this historic peak?

The answer may be found in God's words, "And I carried you on eagles' wings and brought you to Me" (Ex.19:4).

A great experience bears a person aloft with a feeling of consuming exhilaration.

Read the passage in Herzl's diary which describes the state of elation in which the founder of modem Zionism wrote his "Jewish State". Anyone who is totally taken over by a great enterprise or task has the same feeling of being carried onwards by eagles' wings.

In today's Jewish world this is seen in the excitement felt by people from the periphery finding their way back to Judaism, borne away from secularism to spirituality.

The trend is seen everywhere, but, appropriately, especially in Israel, where so many are coming back to their roots and are overtaken by a new fervour in prayer, learning, mysticism and Jewish practice.

The term for this movement is "teshuvah", "return". But this is not quite the traditional meaning of the word. It is more commonly taken in the sense of repentance, the turning away from sin that is the keynote of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

Rabbi Shlomo Riskin has said that in every generation God gives the Jewish people a gift. In our generation it is "teshuvah"; the tragedy, however, is that only secular Jews seem to be taking advantage of it.

But in which sense is Rabbi Riskin using the word? If he means that secular Jews once were sinners and now are back on the straight and narrow, is he right to imply that non-secular Jews are also sinners and need to repent? If he is saying that secular Jews are away from their Jewish roots and need to come back, is he right to suggest that the religious have also strayed from the sources of Judaism?

I believe the answer is yes, and there is a "teshuvah" for religious Jews to do, or at least they have to ask themselves at any given moment whether "teshuvah" should not be on their agenda.

Notice that I have not qualified the word "religious". Paradoxical though it may seem, there are religious Jews who are not halakhically committed, much as I regret the fact.

But every religious Jew, of whatever level of halakhic observance, is duty-bound as a Jew to hear the Divine call, "ko amar Hashem" – "Thus says the Lord" – that mandates full commitment to justice, love and humanity. In this respect there is a "teshuvah" even – especially – for the religious Jew.

We need a new call for a return to justice: how can it be right that members of a people that taught the world justice sometimes cannot endure or forgive one another?

We need a new call for a return to love: if we obey the Shema and love God with our heart, soul and might, how can it be right that we sometimes do not love our neighbours as ourselves – especially those we disagree with?

We need a new call for a return to humanity; if human beings are made in the image of God, it means all human beings, and surely no-one is entitled to appoint him- or herself as God's policeman and decide that some human beings are less worthy of living than others.

And if you say to me that Jews, even religious Jews, are not the only people who sometimes fall short of high ethical standards, I say: "But were Jews not the pioneers of Divine ethics, and is it not the Jewish task to be a light to the nations?"

In an ideal world, every one of us would be constantly borne aloft, as if on eagles' wings, by Jewish visions, values, ethics and attitudes.

It is not yet an ideal world, but the "teshuvah" that ought to carry us onwards and upwards to the ideal world is the constant effort to assess, refine and improve our adherence to the ethics of our tradition.

THE BEGINNING OF REPENTANCE

Repentance has four elements – "charatah" (regret), "azivat ha'chet" (abandonment of sin), "kabbalah" (pledging oneself) and "viddui" (confession).

They are all interdependent and essential. If, for instance, we abandoned sin but did not accompany this act with remorse, it might be that we did not really mean it or even really enjoyed the sin while it lasted.

That is why we also need "charatah", which implies, "Not only have I stopped the sin but I truly regret ever having committed it". On the other hand, the remorse can be there whilst the sin continues because it is hard to extricate oneself from the sinful situation.

The element of "kabbalah", pledging oneself not to repeat that sin, not only confirms the remorse and abandonment of sin; it also says, "I will not do that sin again – not because the circumstances have changed and I am unlikely to be tempted again, but because it is my personal decision not to commit the sin. The decision is my free choice; I am the master of my own destiny".

What about "viddui"? It adds to the other three elements the moral courage to articulate everything to God and face up to His scrutiny and judgment.