For parts I-V, click here.

Part VI The Limitations of the Press

How did the Germans react to Nazi propaganda in the press, since as in all totalitarian regimes, the press plays a critical part in the “political socialization” of the masses? During the early years, there was serious competition between church journals and the party press, despite pressure from the government for the journals to adhere to a uniform message. For those “who could read between the lines,” David Bankier noted, church journals provided another source of information. This alternative to Nazi propaganda became necessary, because not long after Hitler assumed power, the German public had reached “a saturation point…and thereafter [it] went into decline: it was not long before a trend of outright rejection became manifest.”

A credibility gap continued to widen between those who rejected Nazi propaganda and the regime. A September-October 1934 report from the Rhine province (the Rhineland) stated, “the press and radio are not considered reliable.” In response to the distrust of the press, the public stopped reading a number of newspapers. Others depended on church periodicals or the foreign press, both of which experienced a significant increase in circulation. The inability to obtain large quantities of foreign newspapers, which were purchased as soon as they appeared, meant friends, relatives and acquaintances shared the papers until they became unreadable, David Bankier said.

Concern about Influence of the Church

In recognition of the influence of the Church, Joseph Goebbels organized malicious and highly offensive campaigns against the Catholic Church in 1935 and 1936 and again in the spring of 1937 observed German historian Helmut Heiber. In his confrontation with the Church, he called them “the breeding places of perverse sexuality.” In his attack against the priests and monks, he accused them of violating foreign exchange laws and homosexuality. “The whole campaign missed the target,” Heiber explained. When Goebbels viscously maligned the Jews, “antisemitism was nothing new. But when it hit the [20 million] Catholics, a substantial portion of the population got up in arms.”

The virulent attacks by Goebbels against the Catholic Church produced considerable indignation among Christians. Nevertheless, they hardly expressed their objections officially. Those who did voice their reservations publicly like Michael Cardinal Ritter von Faulhaber, Archbishop of Munich, Bankier said were unique. Yet, foreign observers were correct that while these concerns signified “opposition to the Nazis and their methods,” which were often viewed as “brutal and vulgar,” it did not “necessarily” mean “feelings in favor of the Jews.” Those who were embarrassed with the situation, learned to withdraw into non-political solitude.

Daniel Jonah Goldhagen pointed out Cardinal Faulhaber was quite vocal in protesting against Hitler’s euthanasia program during the second half of 1940. Then the cardinal declared: “I have deemed it my duty of conscience to speak out in this ethico-legal, nonpolitical question, for as a Catholic bishop I may not remain silent when the preservation of the moral foundations of all public order is at stake.”

“For Cardinal Faulhaber, was the mass murder of the Jews not an assault on the ‘moral foundations of all public order?” Goldhagen asks. “Why did the bishops not believe that protesting on behalf of the mentally ill and other victims of this [euthanasia] program of mass murder would only hasten their deaths, as the Pope and the bishops are now alleged to have believed would have happened to Jews if they had defended them? Why did the German bishops’ unqualified ‘duty of conscience to speak out’ against mass murder does not apply when the victims were Jews?”

Opposition in Perspective

When the racial principle was applied to the army, the public did not respond, because the military organization remained intact with only 70 officers having to be removed. The few who did protest, Bankier said, opposed the military subordination to the party, not to racial ideology.

“We rarely find rejection of Nazi antisemitism on ethical principles, or indignation based on humanitarian values,” he explained. Declarations of support with the oppressed Jews “were quite exceptional.” The real reason Germans would refuse party requests or appeals, the motivation, which was generally stated in official reports, was quite clear: “very rarely did they exceed utilitarianism or self-interest.”

“Image and Reality” in Perspective

In analyzing the disaffection with particular parts of the political and social scene, it is important to emphasize a couple of points. The criticism was not directed against the National Socialist system itself. Whatever faults were expressed, they were not translated into any practical demonstration of defiance and the regime was not threatened or contested in any way. To be sure, “vast numbers” of Germans identified with Nazi ideology, Bankier declared. Radical Nazis only claimed the government was not preceding fast enough in implementing the “Nazi revolution.” They responded to what they perceived as political stagnation and ideological inertia, and were eager to reawaken the revolutionary fervor. The regime “subordinated these elements to its political objective,” out of concern that the developing activism jeopardized the “very basis of the social and political order.”

Part VII A Wave of Antisemitism

On January 13, 1935, a referendum was conducted to determine whether the Saar Basin should remain under League of Nations administration, returned to Germany or become part of France. More than 90% voted that it should be reunited with Germany. After the plebiscite was completed, a new wave of antisemitism was precipitated by radical elements in Germany, especially the SA (Sturmabteilung), the initial paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, which played an integral part in the rise of Adolf Hitler. As Hitler sought a more moderate approach to governing, their influence eroded. In an attempt to validate their continued need to exist, they revived their combativeness and radicalism. On July 15, an unparalleled surge of antisemitic destruction occurred in Berlin. Shop windows were broken, which became a common occurrence.

On the night of July 15, 1935, historian Moshe Gottlieb noted, approximately 200 German thugs seized, chased and “savagely” beat men and women who looked Jewish “or displeased them by their attitude and appearance” on the Kurfürstendamm, one of the most famous avenues in Berlin. Though they wore civilian clothes, their boots and trousers exposed them as Nazi Storm Troopers. Yelling “Out with Jews,” and “Destruction to Jews,” they expressed their grievances against “unsuspecting and defenseless populace, including some foreigners.”

The attack was the most vicious anti-Jewish incident since Hitler came to power Gottlieb said. He believes the assaults were planned in retaliation for a report in the Völkischer Beobachter, the newspaper of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), that Jews booed a Swedish antisemitic film being shown in a movie theater on the Kurfürstendamm. The report concluded with an admonishment that “such insolence is not to be endured.” A meticulously planned riot followed, staged in front of the movie theater. Apparently, the Storm Troopers had provided the protestors explicit orders since they were observed driving up on down the avenue. Before the police arrived, they left the scene.

Jews were no longer permitted to live in small towns and villages German historian Armin Nolzen stated. Members of the Nazi party publicly demeaned and beat Jews, while Orthodox Jews had their beards and heads shaved. “Popular anger” party rallies and parades and propaganda campaigns were directed against Jews by local district leaders, who provided detailed schedules of meetings and violent events. There were 20,000 honorary local party leaders actively involved in executing party activities. They gathered information for the district leaders about Jewish businesses, what Jews did in their free time and the various Jewish organizations and association to which they belonged.

During the same period, Bankier said, the Nazi police began a campaign throughout the Reich to arrest and incarcerate individuals who violated racial offences. In various areas, offenders were marched through the streets under a poster describing the crime, for example, women accused of fraternizing with Jews. Those alleged of consorting with the Jews were incarcerated for polluting the races, and sent to a concentration camp.

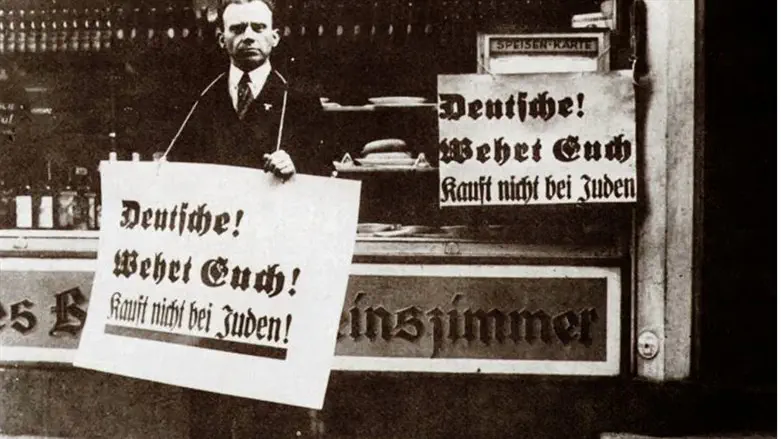

The Nazi Women's Organization district leaders (Kreisfrauenschaftsleiterinnen), Nolzen said, played a fundamental role in the campaign to boycott Jewish businesses and enterprises. The organization sought to encourage women not to purchase any items from Jewish-owned stores and to cease relating to Jews on every level.

The radicals were not impressed with the increase of antisemitic actions, and were disturbed that the authorities stopped them from continuing their terror attacks. The conservative elite viewed this “revolution from below” as a challenge to the existing order Bankier said. The economic institutions were concerned that lawlessness could begin to include all capitalists, which would threaten law and order, and damage foreign relations, tourism, and international trade. Controlling the violence by forbidding unsanctioned individual acts against Jews, was ordered by Hitler and issued by his deputy and the Minister of the Interior. The radicals saw the attempt to inhibit them as a “flagrant betrayal of Nazi principles” as Bankier characterized their response.

The Effect of Antisemitism on the General German Public

The ostensible objective of the antisemitic campaign was to rally the indifferent masses, especially those groups like the lower middle class, who were apathetic. A decline in sales, during a period in which there were price controls, had slashed purchasing power, and freezing of wages all contributed to disaffection with the party. Small merchants criticized the party for not helping them by putting the Jewish owned department stores out of business and nationalizing them, as they had promised. They made the conditions even more acute by allowing food stamps to be redeemed in the department stores, Bankier said. Members of the middle class, which were “one of the Nazis main pillars,” complained the military continued to order its provisions from Jews, and that even when the Germans nationalized the department stores, the stores were not offered to the small shopkeepers to run or own.

With regard to the rest of the society, Bankier said their primary concern was the worsening economic conditions. Antisemitic slogans could not divert attention from their ongoing financial concerns, and the violence only exacerbated the situation. As a Gestapo report in Kassel pointed out, “ It is easier to invite attacks on the Jews, than to persuade the public of antisemitism.” The Germans were looking for stability, which included a definite policy regarding the Jews and churches, so they did not have their lives unexpectedly disrupted by the capricious actions of the extremists.

In contrast to the boycotts and aggression, the removal of the Jews from public life aroused minimal complaints, because it was completed with a limited number of purges to preclude any devastating results, and with practically no interruption of bureaucratic activities. The dismissals cleared the way for the unemployed and the younger generation to advance in their careers. Expulsion of Jews and leftists from the universities and public service created opportunities for advancement “thus contributing to complacency and conformism in the academic and intellectual public,” according to Bankier. Most important, was the lack of an adverse public response, which seemed to imply banning Jews from holding prominent was consistent with the desires of the majority of the German public.

David Bankier quotes Thomas Mann, a German novelist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate, who agreed with this assessment about the removal of Jews from German society. In his diary, Mann wrote: “It is no great misfortune after all that… the Jewish presence in the judiciary has ended.” Later he added: “I could to some extent go along with the rebellion against the Jewish element.”

The only way to control the situation, the Nazis concluded, was to legalize their campaign against the Jews. The Nuremberg Laws promulgated on September 15, 1935, which had been in the planning stages for months, provided the legal basis for Germany’s racist anti-Jewish policy including revocation of Jewish citizenship and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honor to prevent race defilement. Over the next eight years, 13 additional decrees were issued. “The racial laws served as a massive tranquilizer,” Bankier declared. All further measures to exclude Jews from German life as well as riots and arrests were now enshrined in German constitutional law.

Part VIII What Affect Did Nazi Propaganda Have on the German People?

The Years of 1936-1937

A period of comparative tranquility prevailed, especially during the first half of 1936 when Germany hosted the Olympic Games. Though there were practically no assaults against Jews during this time, the public’s callous attitude toward them became more intense and pervasive throughout the country. David Bankier did not attribute this to Nazi propaganda, which the public viewed as “dull and tedious,” but the “wedge” that had been created between the Jews and Germans. Even while Jews were socially segregated, as long as Germans benefited economically from patronizing Jewish stores, they continued to do so, particularly those who were not fanatic antisemites. Some shopped in Jewish stores as a way to express their resistance to the Nazis, not out of concern for the welfare of the Jewish owners.

1938 and Kristallnacht

After the Olympic games concluded, antisemitism began in earnest once again, particularly from the end of 1937. The government accelerated the process of Aryanization, leading to a massive attempt to pressure Jews to leave the country. Jewish institutions, businesses, and private homes were vandalized, Jews were victimized and subject to random arrests. Not to be outdone, the Nazi party began competing with the government on abusing Jews.

Between the late evening hours of November 9 and the early morning of November 10, 1938, gangs of German brownshirts and the SS publicly destroyed and firebombed 267 synagogues throughout Germany, Austria and the Sudetenland. Historian Richard Evans noted that the police and the SS were instructed not to stop the destruction of Jewish property or restrain those committing violent acts against German Jews.

There were a number of responses to this mass pogrom David Bankier found. The large majority of Germans denounced the attacks of “brute force,” while still strongly approving the “social segregation and economic destruction of the Jews.” Many people were humiliated and shamed by Germany because the country was embarrassed throughout the world. Some Germans attempted to “compensate” the Jews for these disgraceful acts. A number of non-Jews felt a very genuine threat that they could be the next target of Nazi terror. In certain areas, the Catholic Church was attacked, when there were no Jews to assault.

Unlike any other antisemitic act, Kristallnacht stirred the educated bourgeoise from their indifference. They had been willing to tolerate the regime’s crude and absence of German Kultur, as long as they could save Germany from Bolshevism. The wanton destruction of property and violence alienated them even further from the Nazis.

Policy of Deportations and Mass Murder

The Germans did not oppose the deportation and mass murder of the Jews because they demonstrated “moral insensibility” to the plight of the Jews, Bankier concluded. Though opposition during the war had to be passive out of fear of the Gestapo or the Sicherheitsdienst, SD (Security Service); that “hardening of attitudes blurred moral boundaries, and that “social atomization precluded a collective response.” Moreover, “a good many Germans were psychologically prepared to accept the reality of genocide.”

Perhaps a letter from SS Obersturmführer Karl Kretschmer (attached to Einsatzgruppe 4a), to his wife Soska explains the rationale for murdering the Jews. On September 27, 1942, he wrote: “The sight of the dead (including women and children) is not very cheering. But we are fighting for the survival or non-survival of our people…. My comrades are literally fighting for the existence of our people. The enemy would do the same. I think that you understand me. As the war is in our opinion a Jewish war, the Jews are the first to feel it. Here in Russia, wherever the German soldier is, no Jew remains. You can imagine that at first, I needed some time to get to grips with this.”

A Final Note

One of the lingering questions about the Third Reich was addressed by George Mosse, one of the greatest historians of the 20th century. “All have wondered,” he said, “whether men of intelligence and education could really have believed the ideas put forward during the Nazi period. To many, the ideological bases of National Socialism were the product of a handful of unbalanced minds. To others, the Nazi ideology was a mere propaganda tactic, designed to win the support of the masses but by no means the world view of the leaders themselves. Still others have found these ideas so nebulous and incomprehensible that they have dismissed them as unimportant.

…[I]t is a fact of history that they [these ideas] were embraced by many normal men… the Nazis found their greatest support among respectable, educated people…. Historians have… regarded this [Nazi] ideology as a species of sub intellectual rather than intellectual history. It has generally been regarded as a facade used to conceal a naked and intense struggle for power, and therefore the historian should be concerned with other and presumably more important attitudes toward life. Such, however, was not the case. It was precisely that complex of particularly German values and ideas which conveyed the great issues of the times to important segments of the population.”

Germany’s Guilt

David Bankier noted that “With the collapse of the Third Reich, the question of Germany’s guilt became a burning question also in the German public. Yet in Germany itself, only a few dared to argue for collective guilt of the entire people.... From the public political viewpoint the question that arose was: What are the limits of liability of the Germans as a people for the actions of the Nazi regime? It follows that the question that troubled the people of that period was not who was guilty for the outbreak of the war, but a completely different question — whether the Germans are guilty of denial of the basic principles of human civilization.”

For Goebbels, the answer was clear as Helmut Heiber points out. On February 1, 1945, he wrote: “Our people will be without guilt, and history will demand us no atonement, for we are fighting and suffering for a higher morality among peoples.” Germany had no choice but to become “the crusaders of G-d,” he said, because they alone could fulfill their “historic duty.” Only Germans possessed the “character and firmness to carry it out. Any other people would collapse under it.”

Dr. Alex Grobmanis the senior resident scholar at the John C. Danforth Society, a member of the Council of Scholars for Peace in the Middle East, and on the advisory board of The National Christian Leadership Conference of Israel (NCLCI). He lives in Jerusalem.