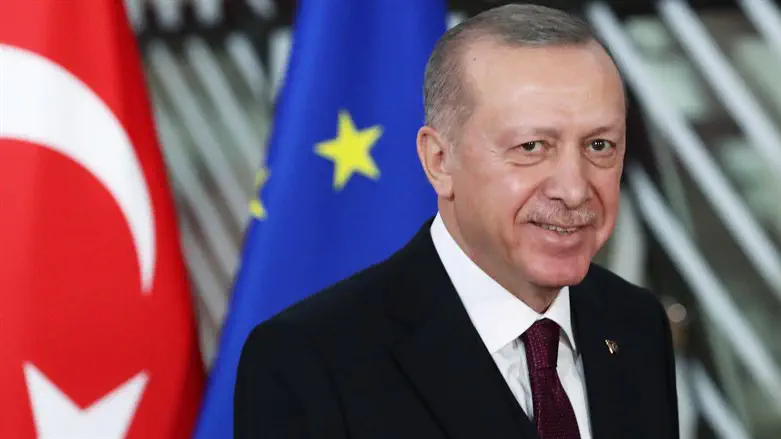

As Turkey continues to dig out from the rubble of a devastating 7.8 magnitude earthquake earlier this month, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is being accused of botching the response. And his previous authoritarian acts may have made the disaster worse than it could have been.

More than 50,000 people died in the earthquake and its aftershocks struck Turkey and Syria. High-rise apartment buildings crumbled to the ground, crushing countless residents.

As horrifying as the death toll is, the actual casualty count could be five times higher than what the government acknowledges, claimed Osman Bilgin, who was appointed by the government to coordinate relief efforts.

Dozens of Turkish lawyers filed a criminal complaint with the Ankara Chief Public Prosecutor's Office against Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and several ministers and governors. It accuses them of "deliberate negligence," bid rigging and malpractice.

Turkey's first responders have been criticized for their relatively slow reactions. The NATO-trained Turkish army was mobilized too late to save many victims.

"It was a total failure in the first critical 48 hours because of the collapse in the chain of command, primarily because everybody was looking for an order from President Erdogan," Turkish journalist and director of the Sweden-Based Nordic Research and Monitoring Network, Abdullah Bozkurt told the Investigative Project on Terrorism. But Erdogan hesitated to activate the military. "He miscalculated what AFAD, the disaster response agency, could handle which turned out to be a totally wrong assumption."

Instead of apologizing for his government's lack of adequate response to the disaster, Erdogan hit back at the criticism and described what happened as an act of fate.

"What happens, happens, this is part of fate's plan," said Erdogan.

What happens next may be in the hands of Turkish citizens. Presidential and parliamentary elections are scheduled this spring, either May 14 or in June, depending on the country's ability to handle recovery efforts and an election.

A coalition of six parties, including one led by former Erdogan ally and Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, is trying to present a united front to defeat him.

It is unclear how the earthquake and the government's response will affect the vote. But the earthquake caused an estimated $84 billion in damage and economic loss, roughly 10 percent of Turkey's GDP, according to a report from the Turkish Enterprise and Business Confederation.

The losses exacerbated the situation for an already struggling Turkish economy.

"That will certainly complicate already existing financial and economic difficulties of Turkey. But the country can still cope with it given the size of its national economy. The real industrial hub of Turkey lies in the West, not in the southeast where the quakes took place. It will have a serious ramification, however," said Bozkurt.

But Turkish authorities reacted forcefully to criticism. "Several people have been arbitrarily detained based on nothing more than their condemnation of the poor state response to the disaster and pleas for more help, Amnesty International reported Thursday.

Such heavy-handed tactics have "been [a] hallmark of Erdogan's governance for years," Bozkurt said. "He shifts the blame to destiny and God to put himself in the clear and takes no responsibility for not taking measures for quake in advance. He thinks his actions are not accountable and [he] can act with impunity."

Erdogan similarly blamed "fate" last October after 41 people died in an explosion at a state-owned mine. Negligence and poor safety measures led to the tragedy. Erdogan ordered an investigation, but his "fate" statements provoked critics who said lax oversight was not a matter of fate.

"Sorry for your loss, May Allah give patience," Erdogan told a woman who lost her brother in the mine. Her brother had warned of a gas leak more than a week before the explosion, but his warning was ignored.

"Why do mass deaths occur only in Turkey? Aren't there mines in other countries in the world?" asked Kemal Kilicdaroglu, leader of the opposition Republican People's Party. "Why don't people die there? They extract more coal than we do. They say, 'We will take action.' Where have you been for 20 years? Who will be accountable to these families?"

"In England and Germany, mine workers cannot reach the level of 'martyrdom' because there are no officials there who put the blame on fate, said jailed Kurdish leader Selahattin Demirtaş. "Nobody should make any more nonsense. Worker massacres are deliberate killings for the sake of greater profit."

In the earthquake, many of the collapsed buildings were relatively new. Officials are accused of allowing contractors to fail to meet strict building codes. Nearly two-thirds of Turkey's buildings remain at risk, said Taner Yuzgec, president of the Chamber of Construction Engineers.

The massive casualties from collapsed buildings pressured Turkish authorities to arrest at least 113 contractors to pacify the growing anger.

Meanwhile, critics say emergency response planning suffered after Erdogan purged the ranks of trained personnel following a failed 2016 coup.

"The lack of effective coordination in search and rescue efforts, aid distribution complicated matter further," Bozkurt said. "AFAD and may other government institutions were hallowed out in 2016 when Erdogan government purged some 150,000 government employees, many ... experienced public officials, and replaced them with partisans and loyalists who have no merits other than party ideology."

While the Turkish government called for help from across the world, some officials were reluctant to publicly express appreciation for some of the countries, including the United States, which stepped up.

That's because the "Erdogan government's main campaign theme is focused on this division between Islam and non-Islam, Turkey versus West," said Bozkurt. "They are concerned that international help that poured to Turkey in the aftermath of the quake may damage that narrative they had worked hard to construct."

As humanitarian aid pours in, even from countries which had political feuds with Turkey such as Egypt and Greece, there are concerns that Turkish authorities might not distribute it equitably.

"Institutional mechanisms and standard operating procedures in Turkey's bureaucracy have been paralyzed since 2018 when Erdogan assumed imperial style presidential powers in Turkey," said Bozkurt. "We see some discrimination in the aid delivery in post-quake efforts as [the] Erdogan government has prioritized constituencies that supported his government in the past."

Some Erdogan supporters peddled conspiracy theories that the United States caused the devastating earthquakes using a secret weapon capable of moving the ground.

The ludicrous conspiracy was widely refuted by scientists.

Observers are comparing this disaster with the 1999 Marmara earthquake, which many believe is what brought the Islamist parties led by Erdogan to power. Will this earthquake similarly contribute to Erdogan losing power?

Bozkurt is skeptical given Erdogan's absolute power.

When Erdogan first came to power, "Turkey had still a functioning free press, [and] political opposition [could] relatively compete in free and fair elections," said Bozkurt. "This time, Erdogan controls entire media, election commission, judiciary and other government institutions. The only thing he has difficulty in controlling is the financial and economic challenges as well as natural disaster such as quake. But he can shape the narrative and shift the public debate around these issues as well."

Erdogan and the ruling APK party's mishandling of Turkey's most devasting natural disaster in a century may seal their fate in the upcoming elections, given they were in hot water over the economy even before the earthquake took place. Playing the religion card will not likely distract the public from the mishandling of this disaster by the Turkish authorities, which exacerbated only its casualties.

IPT Senior Fellow Hany Ghoraba is an Egyptian writer, political and counter-terrorism analyst at Al Ahram Weekly, author of Egypt's Arab Spring: The Long and Winding Road to Democracy and a regular contributor to the BBC.

IPT Senior Fellow Hany Ghoraba is an Egyptian writer, political and counter-terrorism analyst at Al Ahram Weekly, author of Egypt's Arab Spring: The Long and Winding Road to Democracy and a regular contributor to the BBC.

Reposted from the Investigative Project on Terrorism.