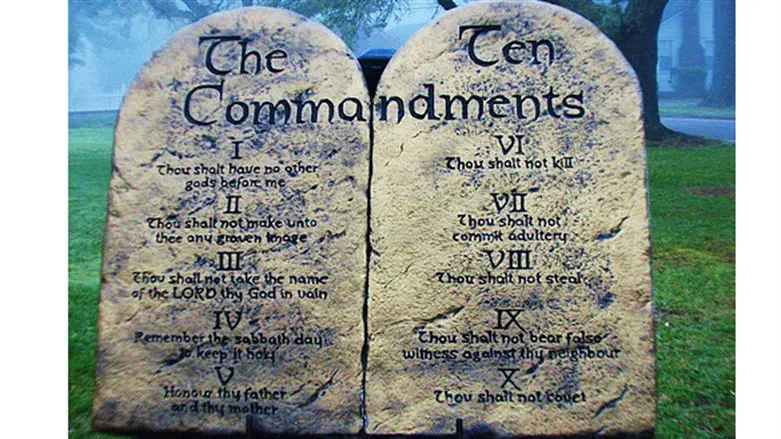

The Ten Commandments come twice in the Torah, the first time in Parashat Yitro (this Shabbat) and the second time (with changes) in Parashat Va’et’channan.

There are actually 613 commandments, of which the Decalogue is a part. Most people say they keep the Ten Commandments but they don’t mention (or often don’t know of) the 613. Our question is why the Decalogue is so famous and the other 603 are generally accorded less priority.

The answer could be that the Ten are basic principles which are spelled out in detail in the 613 mitzvot. This seems to be supported by Professor Eliezer Berkovits, who spoke of our age needing "a theology or a philosophy that does justice to the essential nature of Jewish teaching about God, man and the universe". But in the end the 613 do not lack theology or ethics.

The Ten Commandments speak of knowing God, placing Him above all other deities and committing ourselves to Him; the Shema – coming in the 613 but not the Ten – speaks of loving Him and expressing that love in acts such as Torah study, tefillin and mezuzah.

THE NINTH COMMMANDMENT

The ninth of the Ten Commandments warns us against bearing false witness.

Looked at as a courtroom rule it means that a person who has been where something took place and has seen or heard what occurred must tell the court the truth and not distort the facts.

As a broader principle of ethics it means that data must not be twisted. You must be careful with how you report a situation.

In our generation, false reporting is constantly used to target and hurt Israel. We hear on all sides that the Jewish people have no history of attachment to the Promised Land, that there never was a Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, and Israel has deliberately Judaised historical events.

False witness!!

PERSONAL CHOICE & THE COMMANDMENTS

Q. Why should I obey the Jewish commandments if I don’t want to? Shouldn’t personal choice play a part in my religious observance?

A. "If I don’t want to" is highly subjective.

Try a different context. Can I say, "Why should I obey the traffic laws if I don’t want to?"

Regardless of your feelings we can presume you do not drive on the wrong side of the road because you know you will endanger yourself and others, the law will punish you, and your conscience will feel bad about it even in the middle of the night on an empty street..

Your possibly rebellious feelings are not necessarily the only criterion. Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein says, "Conventional morality holds that anyone and everyone is entitled to do as he pleases provided that he steps on no one else’s toenails; that, as master of his self, he is free to mould his own destiny.

"Halakhah is radically opposed to this attitude; it holds that even with respect to his own personality, man is more trustee than master…

"The whole of halakhah is grounded in profound faith in man’s capacity to choose freely and to chart his own course. It is precisely this faith which makes the stress upon duty – the incessant call to respond to commands – possible. Halakhah grants man less but believes in him more."

The crucial element is that though the Divine command comes from above, man freely and voluntarily responds to it.

JEWISH NEWS & JEWISH JEWS

Q. What makes a Jewish writer?

A. There are Jews who are writers and writers who are Jews, but that does not mean that either group produces Jewish writing.

Jewish writing is ambiguous. If a Jew writes in a Jewish language the result is not necessarily Jewish; if they write in another language the writing can still be Jewish. A "Jewish" writer might be a gentile; it depends on the theme, not the origin of the writer. Writing can totally omit the word "Jew" and yet be Jewish (Kafka doesn’t use the word "Jew" outside his diaries, yet he is a Jewish writer).

Jewish writing is not always pro-Jewish: some Jewish writers rebel against Judaism and Jewishness, and have no interest in Jewish achievement or destiny. Cynthia Ozick says that Jewish writing has a liturgical quality…but what does "liturgical" mean?

SJ Goldsmith says about Josef Herman the artist, "Actually he is a Jewish Jew and a universal painter". A Jewish writer, like a Jewish artist, is "a Jewish Jew".

SHE CALLED HIM "MOSES"

The Israelite leader was Moses. He was given this name when as a baby he was drawn out of the water where his baby crib had floated.

Pharaoh’s daughter said, "It (the name Moshe/Moses) is because I drew him out of the water" – "ki min hamayim meshitihu" (Ex.2:10).

There is a linguistic problem, however. "Moshe" is a present tense participle which literally means "the one who draws out". It is not passive with the meaning "the one who was drawn out".

Strictly speaking the name indicates that Moses was the leader who would bring the people out of captivity, the leader who would redeem Israel from bondage and bring them to their allocated future.

In his d’rashot the Lubavitcher Rebbe speaks of Moses embodying messianic qualities, a notion which emerges from Midrashic sources.

Rabbi Dr. Raymond Applewas for many years Australia’s highest profile rabbi and the leading spokesman on Judaism. After serving congregations in London, Rabbi Apple was chief minister of the Great Synagogue, Sydney, for 32 years. He also held many public roles, particularly in the fields of chaplaincy, interfaith dialogue and Freemasonry, and is the recipient of several national and civic honours. Now retired, he lives in Jerusalem and blogs at http://www.oztorah.com