The dream is to house the first Moroccan-Jewish museum outside of Morocco in a building adjacent to the first full time Sephardic synagogue in the Upper East Side of New York City, called the Manhattan Sephardic Congregation. It is well placed, on East 75th Street, an area known for museums and not far from Central Park, the UN Building, and other tourist destinations.

Why build a Moroccan-Jewish museum in the United States? The word that comes to mind is “bridge.” It represents the emotional bridge maintained by Jews of Moroccan origin and the kingdom. It will join the Museum of Moroccan Judaism in Casablanca, the only museum of Jewish history and culture in the Arab world.

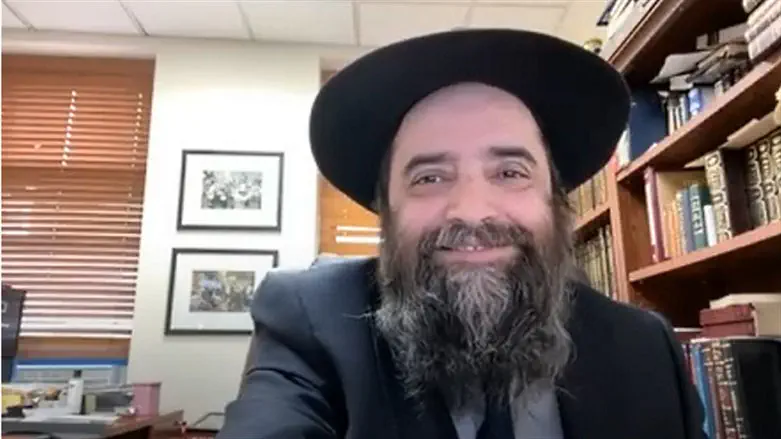

The synagogue’s rabbi, Rabbi Raphael Benchimol, spoke with me on Zoom about his childhood in both Morocco and the United States, about the evolution of the synagogue, and about plans for the museum. In his office, flanked by books on his left, he is quick to smile and happy to share. Regarding the museum, he said:

Recently we came closer to our dream, a dream I always had – a Jewish museum with Jewish artefacts, bridging the close ties between Morocco and the King with the Moroccan Jewish people and also to highlight the incredible heritage we have had for thousands of years in Morocco.

We want to build something beautiful. We want to showcase our friendship with Morocco. In the past, I wrote to the king that this was our dream, and that this could be an opportunity to show the world that there is a possibility for coexistence between religions and peoples. The fact is that we were able to live in Morocco and thrive over the centuries.

In an email, historian Dr. Sophie Wagenhofer, author of the book, Jewish Museum in Casablanca (in German only), shared her view of the significance of the museum in Manhattan:

A museum of Moroccan Jewry in Manhattan can achieve two aims: It can be a place for self-reference and self-ascertainment for the Moroccan Jewish community as a minority in a foreign country, but also towards the far bigger group of Ashkenazi Jews. In this vein, it might also be a voice in the quite contested and controversial discourses on “Arab Jews” and their place within Israeli society, within Jewish history, and in culture in general.

And, of course, it is a project that can foster the positive image of Morocco as a multicultural country, a melting pot that looks back at a great and rich history, a large, diverse Jewish community, and an ages-long coexistence of cultures and religions.

Rabbi Benchimol describes the way Moroccan Jews relate to the king:

As far as I know, and as I was told, the king’s father [Hassan II] was very friendly to Jews, and his grandfather [Mohammed V] protected the Jews during the Holocaust. The Germans wanted to come to Morocco and the king said something to the effect that he is responsible for the Jews as his subjects and he will not submit them to antisemitic laws or transfer. As a result, the Jews have tremendous respect for the king.

I remember King Hassan II as a child in Morocco. Everybody looked up to him. I had the chance to meet the king many years later in New York when he spoke to the Jewish community. When we passed by to greet him, I remember him saying to me, and to the other rabbis, to keep him in our prayers.

A ten-day synagogue trip to Morocco in 2010 proved to be auspicious for the Jews still in Morocco as well as those around the world. Rabbi Benchimol tells how:

When I saw the dilapidated condition of some of the cemeteries and mausoleums, I had a letter sent to the king asking if we could renovate some of the more seriously neglected sites. I received a letter back very soon thereafter where the king stated that he was going to take on this whole project. We held a special ceremony for him at which we recited a special blessing for the king in our synagogue. The ambassador of Morocco in Washington and the Consul General of Morocco both attended.

In 2012, the king, through Ambassador Serge Bardugo [currently the President of Morocco’s Jewish Communities] , awarded me a medal of honor, called the Medal of Knight of the Order of the Throne. Over 300 people attended that event.

By 2015, 167 sites had been restored and 27 rabbis of Moroccan origin from ten countries (including Rabbi Benchimol) offered a “Testimony of Gratitude” to King Mohammed VI.

That same year, on the occasion of its 25th anniversary, the king wrote a long letter to the Manhattan Sephardic Community. He expressed his appreciation for the bonds between the Jews of Moroccan descent and the Kingdom of Morocco and the deep interest he takes in Jewish culture and the Jewish citizens of the country.

These are not just empty words; in 2003, when antisemitism raised its head violently, the king wasted no time in coming down hard on the perpetrators, making it clear that any attack against the Jews of Morocco was an attack against all Moroccans and against his authority.

When sufficient funds are raised to complete the purchase of the adjacent building, Rabbi Benchimol’s dream of a museum in Manhattan -- that will serve as a bridge between Morocco and Moroccan Jews in the United States -- will become a reality.

But that is not the only way that Rabbi Benchimol erects bridges. He was born in Rabat, the capital of Morocco, and lived there until 1975. Then, at the age of 8, his family moved to Florida where he attended a Chabad school, completing high school and rabbinic studies in New York at Lubavitch institutions.

I commented about him being equally comfortable in Ashkenazi and Sephardic synagogues.

Yes. Hashem creates interesting circles. I started off Moroccan, Moroccan, Moroccan, then, because there were no Sephardic yeshivot in Miami at the time, I attended an Ashkenazi yeshiva. The Chabad yeshiva opened their arms and welcomed us free of charge. My parents will forever be indebted.

So here is the circle I mentioned – I attended an Ashkenazi school and I started reading in the Ashkenazi style, and Hashem eventually brought me back to a Moroccan community. So today, when I teach halachot [Laws], for example, based on the Shulhan Aruch [Code of Jewish Law] and otherrabbinic sources, I can also share with my class, from deep personal experience, the differences between Ashkenazi minhagim [religious custom that is not law] and Sephardi minhagim.

In addition, he published a book in English on Rabbi Naftali HaKohen Katz that includes Ashkenazi and Sephardic sources.

I asked Rabbi Benchimol why the synagogue, that is clearly oriented toward Moroccan Jews, calls itself the Sephardic Congregation.

Being the first full time Sephardic synagogue on the Upper East Side in 1990, the original board felt that it would be more inclusive to call it Sephardic to welcome people of all Sephardic backgrounds.

Bridges.