For years now, the first thing I’d read in the morning were the Obituaries. I began to do this many years ago, after more than a hundred and fifty people whom I knew personally, or with whom I’d worked, or whose work I’d admired, went and died “on me.”

The phrase is Biblical. It’s what Jacob/Ya’akov/Yisrael said when his beloved wife, Rachel, died in childbirth. As the senior rabbi of my synagogue, Michael Shmidman, taught, the phrase suggests that Rachel died “all over me,” and Ya’akov’s remaining days and years would forever be shadowed by her loss.

Perhaps my own aging nudged me to read the Obits. It taught me gratitude, daily: I was still alive. It also helped me honor those who’d contributed to humanity both near and dear—and at large, and who were now gone. I, and all other readers, had at least one more lucky day on earth to go about our lives.

I gradually began to notice that Obits were increasingly politicized. Those whose politics aligned with the news venues were only praised and often at length. Those whose politics were reviled—all manner of inappropriately negative anecdotes marred the Memorial.

After this, we cannot return to life as we knew it before, life lived casually. I thought we were supposed to speak only good of the dead; vile gossip, settling old scores, even fears about lawsuits should have no place here. But they do.

I thought we were supposed to speak only good of the dead; vile gossip, settling old scores, even fears about lawsuits should have no place here. But they do.

Now, in the teeth and bowels of this awful plague, I still read the Obituaries—but with a lot more trepidation. Has anyone I know personally died of the Wuhan (Covid-19) Virus? In a gesture of grief and solidarity, I try to read all the names in my local papers, even those in very small print, and in all other papers when and if I can find them.

And suddenly, it seems that articles are appearing about the history of plagues on earth; there are so many reviews of books on the subject. For example, the earliest cities in history have been chronically afflicted by “deadly epidemics.” Tim Flannery, in the NYRB, reviews two books, one by Monica L. Smith, the other by James C. Scott.

People of the earliest cities, both slaves and their masters, suffered from chronic illnesses and “deadly epidemics.” The “Akkadian word for epidemic disease translates literally as ‘certain death.’” The rise of the world’s earliest cities also meant the rise of animal-to-human diseases. The city of Uruk was located on a “low-lying, flood-prone plain” and must “often have been muddy, feces-soaked, and pestilential.” Our earliest cities in the Fertile Crescent/Mesopotamia also instituted quarantines.

This is my fifth week of seclusion. I am sometimes listless and fatigued, often achy, occasionally “lost.” I cannot always summon up the bright energy required to talk to too many people. But I do try to remind myself and others that each day we are safely sequestered means that it’s a day in which we are actively and purposefully vanquishing Death.

May our scientists and physicians prevail. May all who survive this deadly plague learn deep lessons. We must embrace what most we fear, namely, that we cannot return to life as we knew it before, life lived casually. We must be wiser, kinder, more pragmatic, more generous, and forever grateful to those who risked their lives to save ours.

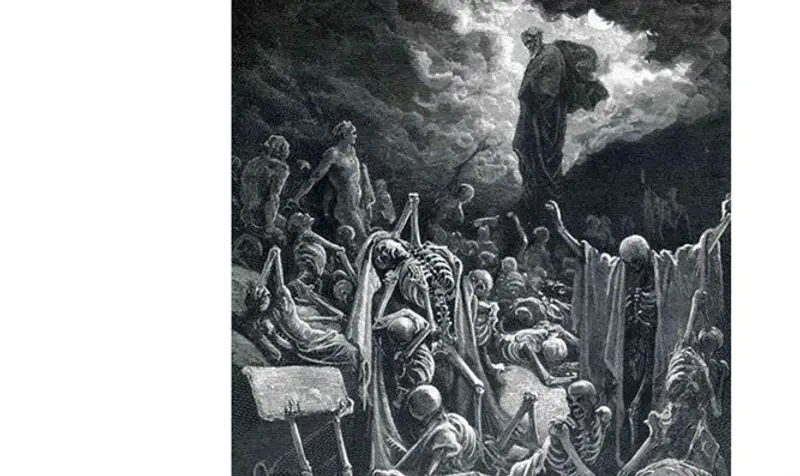

Painting by Gustave Dore, 1866