Throughout our history, Jewish leaders of every stripe have underscored the importance of Bible study. More than an examination of our birthright or an analysis of our history, our most prominent figures have regarded Bible study as the tie that binds our dispersed, diverse and disparate nation.

Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady, the founder of the Chabad Hasidic movement, was a renowned Bible scholar and insisted that his disciples adhere to a study routine that enabled them to complete the entire Tanakh every three months. The founders of the State of Israel, including David Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir, and Menachem Begin, consistently peppered their public remarks with quotes from the Bible to add emphasis and strength. These leaders, and so many others through the generations, urged the Jews of their times to connect with our “Master Text,” promoting the discovery of a common dominator that allows Jews of every background to connect on the deepest of levels.

At the same time, this unifying text has the incredible capacity to exalt and empower the individual. Living up to its “seventy-faced” lore, the Bible allows each student to relate on an intimate level, every persona to find something within the text – a line, word or concept – that expands their worldview and advances their sense of self.

While these two aspects of Bible study have been discussed and debated at length, the source of these powers are not often explored. To my mind, they are both rooted in the unparalleled simplicity and profundity of the text’s literal meaning.

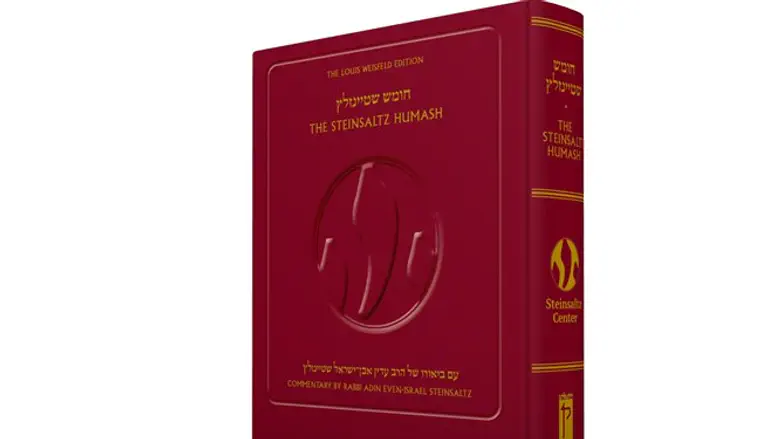

Done right, Bible study begins with a serious assessment of the written word, a personal quest for meaning that precedes any detours into the insights of others. (This is precisely why the Steinsaltz Humash takes the commentator out of the commentary, giving the reader the tools to take control of this very personal exploration process.) In addition to teaching important life lessons about self-reliance and individuality, this method draws out the fundamental human values that are often eclipsed by more intricate interpretation.

For example, the book of Shemot (Exodus) is full of laws concerning interpersonal relationships, and a simple reading of the verses highlights the genesis of our core values. While the commentaries have much to say about chapter 23, verse 4 – “If you see the donkey of your enemy fallen under its load, do not leave it there; you must help him with it” – a very basic reading of the text reveals it to be among the many origins of the value of charity: not only do we have to care about that which is not ours, but this concern must extend to the possessions and wellbeing of our enemies.

Unfortunately, we’ve lost the script over the last few generations. While the Bible continues to unite and inspire us, we’ve lost sight of the importance of the act of Bible study itself, of finding that crucial deeper message within the written word.

While other religions borrow from the Bible, realizing that the values contained within are the keys to navigating the world around us, so many Jews have turned their backs on Bible study, opening the door to confusion, disillusionment and disconnection. To be sure, this is causation rather than mere correlation.

When we all study the same text and agree on the core values borne out of this analysis, we are drawn together.  When we don’t connect to the “basics” and can’t seem to find salvation or even solace in the text, we look elsewhere. But when we all study the same text and agree on the core values borne out of this analysis, we are drawn together. Our individualized study may well lead us to different conclusions and interpretations about specific concepts or plot points, but the inherent values punctuated by our exegetical exploration can bridge any gap – cultural, geographical, ideological or otherwise.

When we don’t connect to the “basics” and can’t seem to find salvation or even solace in the text, we look elsewhere. But when we all study the same text and agree on the core values borne out of this analysis, we are drawn together. Our individualized study may well lead us to different conclusions and interpretations about specific concepts or plot points, but the inherent values punctuated by our exegetical exploration can bridge any gap – cultural, geographical, ideological or otherwise.

What’s more, regular Bible study forces us to take the time to ask the important questions. Who are we? Why are we here? What is the purpose of living as a Jew and following this defined set of beliefs? Bible study helps us refine our outlook and answer these burning questions, or at very least allows us to distill and articulate the questions in a way that won’t drive a wedge between us and our heritage.

By engaging in regular Bible study, we can approach each new communal Bible reading cycle with a rekindled desire to unearth the hidden meaning in every portion. Indeed, even the stories are worth contemplation, as their numerous lessons push us to become better individuals and a more virtuous society.

The binding of Isaac, for example, is at once beautiful and horrific, but it forces us to determine how far we should go in our devotion to God, and what acts should be considered inhumane. And the perplexing and heart wrenching saga of Jacob’s life is an epic tale of misconduct, impropriety and deception that makes us wonder about its inclusion in the Bible, which (I would argue) is exactly the point. That speculation, coupled with the understanding that the text must be telling us something more, leads to the development of a solid core of conduct for humanity.

Though the Bible is a guidebook for better living, it doesn’t achieve this lofty goal by leading us by the hand. Instead, it challenges us, compelling us to ask the tough questions, discover what makes us tick, and reclaim our morality. In this way, regular Bible study promotes national unity, stimulates spiritual individuality, and allows us to pave the way for a more beautiful and ethical world – one line, word or concept at a time.

Rabbi Meni Even-Israel is the Executive Director of the Steinsaltz Center (www.steinsaltz-center.org), a unique pedagogical accelerator that develops tools and programming that encourages creative engagement with the texts and makes the world of Jewish knowledge accessible to all.