(JNS) For years, Israel has been taken advantage of on the issue of exchanges of prisoners and fallen soldiers. When it has managed to strike an agreement, it had to pay an high price in exchange. When it put its foot down and resisted, it got a much more sensible deal.

The death of Jenin terrorist Daoud Zubeidi is an opportunity to change the rules of the game and turn the blackmailers into blackmailees.

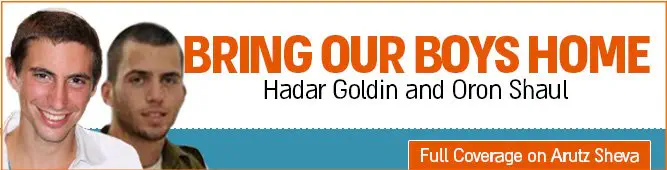

True, a funeral has been held for Lt. Hadar Goldin, who fell in 2014 during Operation Protective Edge, although his remains are held by Hamas. True, Staff Sgt. Oron Shaul, who fell in the same battle, has been declared an IDF casualty whose burial place is unknown, although the presumption is that his remains are also held by the terror group, along with two captive Israeli citizens.

In Protective Edge, the IDF tried to learn from the mistakes it made after the abduction of Sgt. Eldad Regev and Sgt. Ehud Goldwasser by Hezbollah in 2006. The IDF declared Goldin and Shaul casualties, in hopes that it would aid Israel in negotiations. But Israel released detainees and the bodies of terrorists too early, and thus gave up the leverage it could have used against Hamas.

The redemption of captives is not a modern issue for the Jewish people, and it was discussed, for example, in the Mishnah, which says, “We do not ransom captives for more than they are worth.” This means that the conditions for the release of a captive must be reasonable.

Here is where it gets complicated. What is considered “reasonable”? Does it make a difference whether the soldier is dead or alive? The equation is complicated not only due to a halakhic aspect, but also by social and state responsibility. At what point can the state say that the price for the exchange is too high?

In 1978, Israeli soldier Abraham Avram was released in exchange for 76 terrorists, who included Rima Tannous, who several years earlier helped hijack Sabena Flight 571.

In 1997, the body of fallen IDF soldier Itamar Ilya was released in exchange for a dozen terrorists, who included Hadi Nasrallah, the son of Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah.

In 2004, the bodies of IDF soldiers Adi Avitan, Omar Sawaid, and Benyamin Avraham, who were killed and abducted in a Hezbollah attack on Mount Dov, were returned to Israel along with Elhanan Tannenbaum, an Israeli civilian held by Hezbollah, in exchange for 400 terrorists and another 35 additional prisoners, among them Abdel Karim Obeid and Mustafa Dirani, who had at one point held missing Israeli Air Force navigator Ron Arad.

Four years later, Israel received the bodies of fallen soldiers Eldad Regev and Ehud Goldwasser in exchange for the murderer Samir Kuntar, who in 1979 took part in an attack in Nahariya in which three members of the Haran family and a policeman, Eliyahu Shachar, were murdered. Together with Kuntar, Israel also released four other prisoners and the bodies of 199 enemy fighters.

Perhaps the most famous case was in 2011, when Gilad Shalit was released in exchange for 1,027 Palestinian prisoners after more than five years in Hamas captivity. Several years earlier, Israel also released two dozen terrorists in exchange for a video of Shalit.

Do you see the pattern? The enemy has leverage—women, terrorists hailed as heroes, family members of prisoners. Meanwhile, Israel refuses to play any of its cards.

Again and again, it released terrorists and symbols of Palestinian Arab 'heroism/ too early. Perhaps it is not pleasant to go from being the one who is taken advantage of to the one who takes advantage of another, but Israeli leadership and society must understand that more of the same will not bring about a change.

We have an opportunity to change the rules of the game. We should hold on to Zubeidi’s body and, from now on, the body of every valuable terrorist.

The time has come to let the other side know that we will no longer tolerate being blackmailed. To release Zubeidi’s body too early would undermine the very reason our soldiers were sent into battle: to fortify the security of the state.

Oded Revivi is the mayor of Efrat and the former chief foreign envoy for the Israeli communities in Judea and Samaria.

This article was originally published by Israel Hayom.