Power doesn't corrupt people; people corrupt power--William Gaddis (1922-1998).

Much has been aired about the glaring defects of the current Israeli government—about how it rewards deceit, how it disregards disloyalty, and how it undermines the founding precepts of Zionism. But one of its more egregious aspects, generally overlooked, surfaced albeit obliquely last week with news of the imprisonment of several senior members of Finance Minister Avigdor Liberman's faction, Yisrael Beyteinu.

"One of the largest cases ever of political corruption"

Former deputy minister Faina Kirschenbaum of the Yisrael Beyteinu faction began her 10-year sentence at the Neve Tirtza women’s prison in Ramle, for her role in arranging an extensive kickback scheme, widely considered one of the largest cases of political corruption the country has seen. Kirshenbaum, 66, was sentenced in July following her conviction for bribery, tax offenses, money laundering, fraud, and breach of trust.

The Times of Israel reports that the charges against her involved inappropriately funneling large sums of money to various organizations, which allegedly made dubious "nepotistic appointments", and channeled some of the funds to public service officials in the form of cash kickbacks and benefits.

Apart from her prison sentence, the longest ever imposed on a serving or past Knesset member for corruption offenses, she was also fined almost a million shekels (over a quarter-million dollars).

Convicted along with Kirschenbaum and sentenced to 7 years imprisonment was David Godovsky, Yisrael Beyteinu's chief of staff and reportedly Liberman's "right-hand man", on charges that included bribery, facilitating bribes, conspiracy to commit a crime, and fraudulently obtaining benefits under aggravated circumstances.

Kirschenbaum was in charge of the party’s so-called “coalition funds”, received by all parties in the government, which amounted to 1.2 billion shekels ($380 million) in public funds, allocated at the discretion of the party. According to the court’s ruling, Kirschenbaum took 2 million shekels in bribes for herself and her party. Citing from the ruling, Haaretz noted: “…the accused [i.e. Kirschenbaum] bypassed proper norms of governance, taking public funds for her personal use … she distributed the booty she extricated from public coffers generously among her friends and family members, as well as taking some of it herself.”

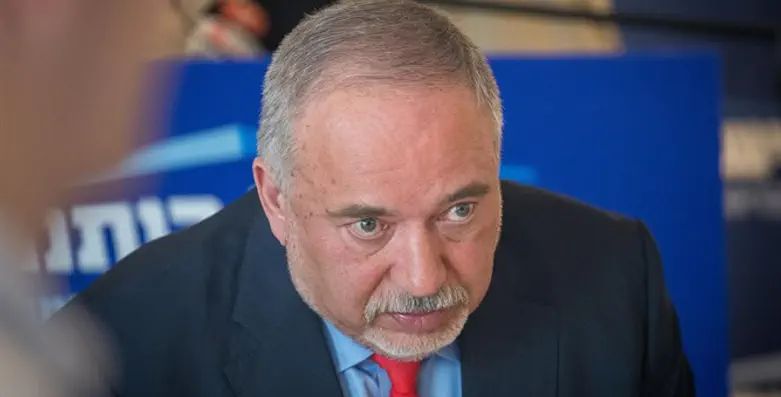

Liberman: The elephant in the room

Apart from the harshness of the sentences, what provoked raised eyebrows was an element perplexingly and perturbingly absent from the entire episode: Any sign of the involvement of Yisrael Beyteinu boss, Avigdor Liberman in Bennett's crazy-quilted coalition.

For example, Baruch Kra, a well-known legal commentator wrote: "…we must discuss the elephant in the room—or more precisely, the elephant in the public coffers—MK Avigdor Liberman."

He points out: "Liberman, leader of the party from the day he established it, was not a suspect in this episode, was not questioned, did not even testify. This is one of the puzzling lapses in this episode—because whichever way you look at it, it involved the coalition funds allocated to the party he headed."

Kra ponders: "Did he really not know anything of what happened there? Of what took place there?"—and goes on to refer to the 2016 testimony of one of the defendants-turned-state-witness, who describes how money was transferred, concealed in parcels of fruit and cosmetics, to a Yisrael Beyteinu lobbyist, reportedly with the full knowledge of Liberman.

Pointedly he asks: "Was this not sufficient to at least summon Liberman to testify?"—and raised the question of whether the prosecution was still so shell-shocked from their failure, after a decade-and-half long investigation, to prove charges against Liberman in a previous proceeding, that it did not bother to probe into Liberman's awareness of what went on in his party.

Mysteriously disappearing witnesses

Similar—indeed, even more somber—sentiments were expressed by former Yisrael Beyteinu MK and erstwhile Liberman colleague, Danny Ayalon. Ayalon, who served as deputy Foreign Minister on behalf of Yisrael Beyteinu, and Israel's ambassador to the US, wondered why Liberman had not been indicted. Hinting heavily at foul play during Liberman's previous legal entanglement, he wrote: "There were three witnesses who disappeared…one witness recanted on her early testimony…" (See also here.)

Ayalon speculated that there might be "another reason" that Kirschenbaum opted not to implicate her boss and not to provide further information on his involvement: "…perhaps the smell of prison scares Kirschenbaum less than ending her life in some other way [sic]."

Even more explicit was a column by investigative journalist, Yoav Yitzhak, who argued that Kirschenbaum (and Godovsky) could have received lighter sentences, had they "agreed to provide information on Liberman's part in the offenses committed in this affair." However, according to Yitzhak, they both preferred to "keep their silence because of their concern for their personal safety and their wish to protect their families [sic]—and their desire to receive in the future—while serving their time in prison—compensation from Liberman and/or oligarchs who are associates of his."

Yitzhak provides a list of half a dozen witnesses who were supposed to testify against Liberman in an earlier episode and met mysterious deaths, allegedly committed suicide, or suffered sudden lapses of memory, preventing them from recalling previous information they had provided. He makes the case that the disturbing fate of previous witnesses and the hope of material compensation for loyalty to Liberman compelled Kirschenbaum and Godovsky to hold their tongues rather than implicate the Yisrael Beyteinu head in any wrongdoing, in which they were involved.

Clumsy clutz or Cosa Nostra capo?

Indeed, anyone even remotely familiar with the inner works of the Yisrael Beyteinu party would be aware of the highly centralized manner of its functioning and in which its decision-making process works. Accordingly, it is difficult to accept the fact that Liberman, who was closely involved with, and certainly aware of, everything and anything of consequence that transpired within the party would be oblivious to the transfer of hundreds of millions of dollars accruing to the party—and would not at least be actively involved in approving their allocation.

It is thus difficult to disagree with Yisrael-Hayom journalist, Ariel Kahane, who found it "astonishing that the party chairman [Liberman] was not even questioned" following testimony that he was fully apprised of the illicit money transfers.

There are clearly only two possibilities regarding Liberman's involvement in what has become known as the "Yisrael Beyteinu affair".

The first is that, despite it being highly implausible, Liberman was unaware of the illegal monetary operations in his party.

The second—and more plausible—alternative is that Liberman was aware—perhaps even involved—in the illegal shenanigans that went on in his party.

Neither option bodes well for Israel.

If the former is true, the nation's finance minister is hopelessly incompetent in managing the financial affairs of his own tightly controlled party, which necessarily augurs ill for his ability to manage the nation's finances.

If the latter is correct, the man controlling the nation's coffers is little more than a mafioso-style gangster, casting a Cosa Nostra-like shadow of fear over party members, who would rather languish in jail than risk the consequences of testifying against their "capo"…

Just another aspect of Bennett's "government of change"…

Martin Sherman is the founder & executive director of the Israel Institute for Strategic Studies