Will Emmanuel Macron, the incumbent Left of Centre president of France, be reelected for five years in 2022 ? If opinion polls are to be believed, yes, though a lot can yet happen.

France’s electoral system may look familiar to Americans. In the United States, candidates are nominated in party primaries and then there is the presidential election proper. In France, there are two rounds of ballot: anyone endorsed by 500 elected officials can run in the first round, scheduled for April 10. The second and decisive round, on April 24, is restricted to the two first round frontrunners.

Until recently, Macron was expected to lead the first round with 23 or 24 % of the vote, and the second with 54 to 64 %, depending on his adversary. According to an Harris Interactive/Challenges poll released on December 1, the Hard Right leader Marine Le Pen would be the president’s strongest adversary, carrying 46 % of the vote in the second ballot, whereas Jean-Luc Mélanchon, the French Jeremy Corbyn, would be the weakest, with 36 % only.

Things have been changing, however, since the nomination on December 4 of Valérie Pécresse, the president of the Greater Paris region, as the conservative, Right of Centre, candidate.

Whereas almost all French political parties, including the Socialist Party, have undergone a steep decline over the past years, and Macron’s own party has never really taken off, the French conservative party – Les Républicains (LR) – still carries weight: it is the main opposition group at the National Assembly, and it controls the five richest and most populated regions of France. Moreover, the candidate was selected in a fairly democratic way, through an internal vote that involved over 100 000 party members. Pécresse, the first woman ever to lead the conservatives, led by about 60 %, but Eric Ciotti, an hardline contender, proved quite strong as well, with about 40 %.

So much so that new polls show something like a sudden conservative surge. An Elabe/L’Express/BFM TV poll released on December 7 suggests Pécresse would get 20 % of the vote on the first round, thus overpassing Le Pen, and beat Macron on the second in a 52 % to 48 % duel. In fact, Macron and the conservatives share a global moderate constituency : just as Macron attracted parts of the LR vote in the last election in 2017, some Macron voters may switch to Pécresse in 2022.

There is however a thoroughly unknown factor in the coming French election : the Rightwing outsider Eric Zemmour, who declared his candidacy on November 30. In spite of concerns for a Covid-19 new wave, he gathered 12 000 supporters in a public rally in the Northern Parisian suburbs of Villepinte on December 5.

For about six months, throughout summer and fall, Zemmour, a former columnist for Le Figaro, a debater honed by years of radio and TV talk-shows, and the author of several best-selling essays, set the tone of the campaign.

Basically, he dwelt on the issues that the mainstream parties had been unwilling or unable to cope with for years and that Le Pen’s National Rally (formerly National Front) had picked up : the negative impact of mass non-European immigration, the challenge of radical Islam, the cost of globalization, the defense of France’s national identity and sovereignty. However, he recrafted them in such an effective manner that, by mid-October, he had risen to 18 % of the voting intentions and there were talks of a Zemmourist takeover bid on both the National Rally and the most conservative wing of LR. All of a sudden, L’union des droites, a unfulfilled 40 years old dream (or fantasy) of bringing together the Far Right, the classic Right and the Right of Centre, seemed to be at hand.

By now, Zemmour seems to be receding to less than 15 %, and some observers wonder whether his campaign will not unravel as quickly as it had grown. In some ways, he himself is to be blamed. 77 % of the French, according to an Elabe/BFM TV poll released on December 1, view him as « arrogant ». The video by which he declared his candidacy can hardly dispell such an impression. For ten minutes, against the same musical background as Tom Hooper’s Kings’s Speech (Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony), he lectures the nation about its fate and claims to be its latter days savior, as the charismatic heir of Joan of Arc, Napoleon and Charles de Gaulle.

A further problem is that while Marine Le Pen has been eager since she took over the National Front in 2011 to distance it from her father Jean-Marie Le Pen’s extremism and to shear it from neo-Fascist or antisemitic undertones, Zemmour has happily done the opposite. His successive books on France - Le Suicide français (The French Suicide), Destin français (French Destiny), La France n’a pas dit son dernier mot (France Has Not Said Its Last Word) – may be in read in part as a brilliant assessment of the current crisis. However, they can also be understood as a recycling of Far Right idelogies, from the neo-Royalist doxa of Charles Maurras to Catholic fundamentalism. Such tricks endeared him to the many National Front sympathizers that did not support Marine Le Pen’s aggiornamento, or to Sens Commun, a Catholic network that resisted the legalization of same sex marriage nine years ago, but repelled other potential voters.

Zemmour’s drift to the Far Right was compounded by his awkward stand on Jewish issues. On the one hand, he is the most traditional Jew ever to have entered French politics: he was educated at Jewish schools only until college, and he raised a somehow observant Jewish family. On the other hand, he disclaims many of the political attitudes associated with Judaism: not just human rights liberalism, but Holocaust awareness, Zionism and pro-American conservatism as well.

This led him to very controversial or even at times scandalous statements on the Dreyfus case, the Vichy handling of French Jews duruing WW2 or even the right of the Sandler family, as French Jews, to bury in Jerusalem their children murdered by a jihadist terrorist in 2012. Whether he did it tactically, to strenghthen his image as a French patriot, or out of deeply held convictions remains to be seen. In the meantime, many conservative French Jews are ready to vote for him no matter what (and French Jewry is quite politically conservative nowadays); but many of the Rightwing Gentiles who like his books may be unprepared for a Jewish president.

Finally, one must consider the wider angle. Zemmour enjoyed until very recently, as a Rightwing intellectual, unprecedented access to the media. Yet this is now being withdrawn from him. Does it mean that he has been manipulated by higher powers? He has certainly been a game changer in many areas. Once the job is done, he may be disposed of.

Or perhaps he can rebound. In the aforementioned candidacy video, he names the enemy: Macron, of course; the LR leaders except Ciotti ; the socialist candidate Anne Hidalgo. Marine Le Pen is spared, understandably. But so is the pro-immigration Leftwinger Mélanchon. Zemmour’s trump card may be, accordingly, not to run as the champion of L’union des droites, but rather as the leader of a global revolutionary assault, from Right to Left, on the established order.

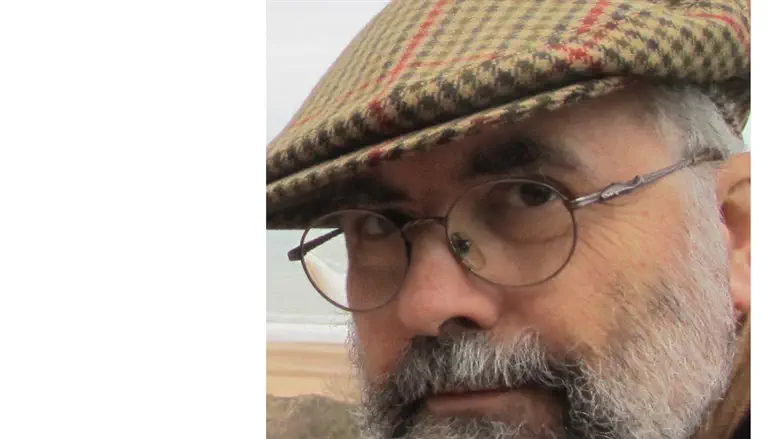

Michel Gurfinkiel, a French public intellectual, is the former Editor of Valeurs Actuelles, and a Ginsburg/Milstein Writing Fellow at Middle East Forum.

Sent to Arutz Sheva by the writer.An earlier version of this op-ed was published by The New York Sun on December 4.

© Michel Gurfinkiel, 2021.