GESHEM

Sh’mini Atzeret is marked by "Geshem", the prayer for rain.

Though everyone knows the ditty, "Rain, rain go away, come again another day", life would be lacking without rain.

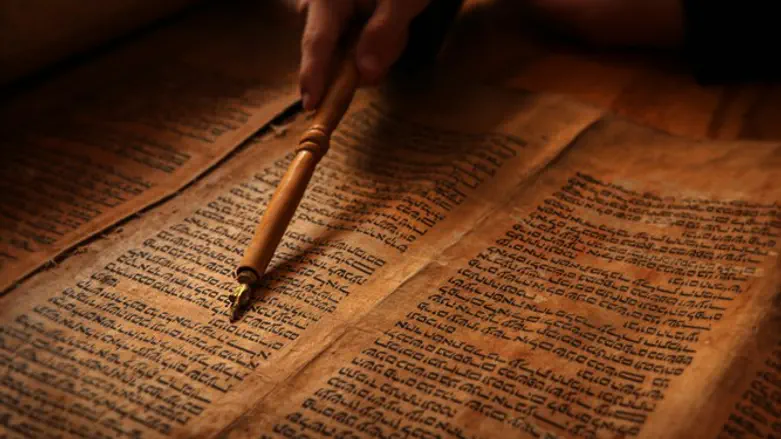

Many poets produced texts for the "Tal" (Dew) and "Geshem" prayers. The conventional Ashkenazi versions are attributed to Elazar Kallir, the religious poet of the early Middle Ages. Kalir’s "piyyutim" (liturgical poems) – which also include sections of the High Holyday services – have an intricate style with constant resort to acrostics.

The author brings in Biblical, Talmudic and Midrashic allusions which generally only a scholar can appreciate, though his Tal and Geshem are not as complicated as his High Holyday piyyutim.

Kalir’s prayer texts have a range of musical settings; Tal has become specially popular by reason of Yossele Rosenblatt’s lively version which many synagogues utilise. Both poems are lent especial awe and solemnity by the white High Holyday robes worn by the cantor. Indeed it must be said that without Geshem and Yizkor (memorial prayers), Shemini Atzeret in particular would seem empty.

In Israel the day is combined with Simchat Torah, creating a strange mixture of emotions.

THE SIMCHAT TORAH MYSTERY

Parading, singing, dancing and feasting combine to make Simchat Torah one of the fun days of the year.

There is a good reason to celebrate – the end of the cycle of Torah readings – but why delay it until a month after the end of the year? And why tack it onto Sh’mini Atzeret?

There were originally two main traditions – completing the Torah cycle in one year and completing it in roughly three years. Those who followed the annual cycle had a range of usages as to when to mark the change-over from one year to the next, with some choosing Rosh HaShanah and others waiting until the end of the festival period of the month of Tishri.

The festival period concluded on Sh’mini Atzeret, and the custom of having a two-day yom-tov (one day in Israel) created an opportunity for a special celebration of the change-over of Torah readings.

TORAH READING AT NIGHT

Some congregations read the final section of the Torah on Simchat Torah night, not just in the morning.

The custom differs from place to place but the basic rule of K’ri’at HaTorah is that it is restricted to the morning. However, since the Torah scrolls have been removed from the Ark for the purpose of the circuits of the synagogue, some argue that there should be a reading so that the scrolls will have been used for their regular purpose.

According to the Rema, "Each place follows its own usage". If a reading does occur it is of the first portions normally associated with Simchat Torah morning, and the High Holyday melody is used.

CALLING UP THE BRIDEGROOMS

Normally we call someone to the Torah with the word, "Ya’amod" – "Arise!" – followed by the person’s Hebrew name. Simchat Torah is different.

The Chatan (bridegroom of the)Torah and Chatan B’reshit, the title for the person who is called up for the last words of the Torah and the person called up for the first words of the Torah, are called up with a highly elaborate formula beginning "Mer’shut", "With the permission of the Almighty and the righteous band of the blessed congregation", which asks God and man to approve the choice of the chatanim.

Whilst not a rhyme of the simpler kind known today, "Mer’shut" is made up of a series of sentences each ending in the syllable "ra" ("nora", "zimrah", etc.).

The version used for the Chatan B’reshit is by Menachem ben Machir (11th cent.); it was probably written later than the formula used for the Chatan Torah.

As we see from the famous 11th cent. liturgical work from the school of Rashi, the Machzor Vitry, a similar formula was used in medieval Franco-German communities when an ordinary bridegroom was being called to the Torah.

The idea is clearly that anyone singled out for honour must have the approval of the congregation and not be imposed upon them. This is not only an expression of the democratic principle that lies behind Jewish community life, but it also teaches a basic lesson in good manners – that decisions should be based on consultation.

We learn this from God Himself, who, according to midrashic tradition, asked the angels’ opinion before He created the world.

It must be said that not all the angels voted in favour of man being created. Man, some of the angels argued, would be unworthy to inhabit such a beautiful world; he would lie and cheat and destroy, and it would be better not to create him (B’reshit Rabba ch. 8).

God overruled the opposition – otherwise, we would not be here to tell the story – and it is up to us in every age to make sure that the angel critics are not proved right.

Rabbi Dr. Raymond Apple was for many years Australia’s highest profile rabbi and the leading spokesman on Judaism. After serving congregations in London, Rabbi Apple was chief minister of the Great Synagogue, Sydney, for 32 years. He also held many public roles, particularly in the fields of chaplaincy, interfaith dialogue and Freemasonry, and is the recipient of several national and civic honours. Now retired, he lives in Jerusalem and blogs at http://www.oztorah.com