For the beginning of the story based on a Midrash, click here.

Consider the compacts that hold him together: the compact between Balaam and kings; between them both and armies; between Balaam and God, who counts up the dirty vices and works of spite that make Balaam a by-word for dark powers.

Imagine him debating a fatherly priest like Jethro who believes in God the just and the merciful. Never mind that. Balaam and the landowner Job whose god is buying low and selling high for a return on capital, inhabit different planets. `

The palace gardens are alive with heat-maddened beetles and hunting horns echoing through brakes and thickets. High Priest Jethro, whether knocked by the sun or conflicted into paralysis, has sagged into a bundle of clothes. The contest of wills has proved too demanding. Jethro falters and trips over his walking stick. Job grabs an elbow. Steadies him. They sit him down on a low wall. A drain of ditchwater runs behind it. In the near distance the Nile simmers like hot water.

‘Easy now,’ says Job, bending to the lion size face. ‘Balaam – some foot rest for our lord Jethro. But he levers the stick like a maypole to get back on his legs. After a minute they’re heading back to the palace. The tread of the priest is heavy. The hair on his neck is bristling like a mastiff being led to a bear.

‘Come now,’ Balaam says cheerily, ‘that’s not how to face down the king.’

‘I assure you, no way do I intend to face him down,’ says Jethro, hitching up his robe.

“What – you intend to sit on the fence?’ Balaam says. ‘I doubt it will be too comfortable.’

‘More comfortable than where you’re going, endorsing slavery.’

‘Not to hell,’ Balaam says. ‘I trust not. What do you think, master Job? Are we headed for hell?’

‘Balaam, I haven’t your power to access the Almighty’s mind,’ says Job, speaking truer than he could ever dream. Balaam takes Job’s rudeness to launch out at Jethro.

‘Have I got you clear? You object to the labour project because you can’t live with your conscience?’

‘Yes.’

‘You see no problem with that?’

‘No.’

‘Not the Israelite problem? Consider how it began. Joseph was in a pit of vipers and scorpions. Along came a caravan of Midianites. Your people, Jethro. They bought the boy from the brothers. They hauled him out. They sold him onto Ishmaelites who sold Joseph in Egypt. Am I making myself clear?’ Balaam’s face is a mask of malice. He’s brought Jethro to a dead stop.

‘Followed,’ Jethro says, ‘but to where?’

'Then I will continue the story. Joseph the Viceroy of all Egypt invited his father who is Israel, or Jacob if you like, to come with seventy of the family to make Egypt their home. Those were the original breeding stock. What is the number now, did the king say? Three million. Adults, my lord, Jethro, not counting the baby boomers.’

Job is outraged. ‘It’s a hard thing Balaam, sir, to make a man account for compatriots of a long dead generation.’

Jethro says, ‘Why don’t I make you account, Balaam, while we are playing this game, for Joseph who brought the Israelites to Egypt. If your grandfather Laban had not married a daughter to Jacob, who fathered Joseph with her, who became the Viceroy who got Pharaoh to allow the Israelites to relocate, you too should be held to account for the problem. All outcomes can be managed. Outcomes can even be massaged. Make them into whatever suits us. All that comes to pass, passes by God’s design, with our bitter foibles making use of the outcome. The King of Kings writes the story. We make use of pieces of it. I am astonished at you master Balaam, though not disappointed.’

When crossed Balaam can widen to fill an opponent’s vision. Different dimensions are available to his body. ‘You won’t let me finish, he says. ‘Grant me that courtesy and I can make my point instead of the one you made for me.’

‘Well?’ Job says, ‘what is your point?’

‘Don’t mess with God.’

Jethro laughs. ‘You talk about the Creator as if he’s a neighbour you go to for sharing a flagon of homemade wine.’

Balaam leans forward. ‘Let’s be clear. God, whether for good or bad, made a covenant with Abraham, the bris bein habetarim, the covenant of parts. One of the parts decreed a bitter exile for Israel. Abraham accepted the terms meekly – why he didn’t bargain for lives like he did when God was about to destroy Sodom, I have never understood. But there it is. The chosen people are going to be enslaved in Egypt. God makes Pharaoh the instrument of that. So don’t tamper. My grandfather tampered. He made deal after deal with Jacob. The flocks of his greasy son-in-law grew and grew and grew.’

‘Oh, but that’s different,’ Jethro says. ‘Laban cheated. My motive is moral. I seek to prevent a cruel bondage. Make God angry? I can’t see it. God made beatific promises to Abraham, He blessed Jacob to father tribes – only for them to be turned into slave termites? God will punish me for wanting human treatment for humans made in His image? You believe that? I’d spit on anyone who did.’

‘That might well be,’ Job, ever practical, says. ‘But in thwarting what the king’s set on doing we are thwarting – as Balaam said – what God needs to happen. Who are we anyway, to define cruelty? Maybe the Almighty has a different notion of it. Second guessing God is to play God.’

‘Thank you master Job,’ Balaam says. ‘And anyway, God has decreed a reward for the slaves. They’re going to inherit the land of Canaan. Picking out one event in the whole story invites faulty thought.’

Jethro: ‘When God promised Abraham that his seed would inherit land, He had Canaan in mind. Canaan, Balaam, not Egypt. Egypt is the exile. The Israelite Patriarchs and matriarchs lie in Machpela in the plains of Mamre. Burial always cements inheritance. There’s no famine now in Canaan. Let the Israelites go up from Goshen to settle it. If you believe the revelation, why wait for the suffering and death ordained by it? And Job – you’ve got land enough to hold the three million, with more to spare. ‘Make Pharaoh an offer.’

‘It’s too late for that,’ Job says. ‘The Israelites have become too useful to let go, and too dangerous to keep free. Bondage would solve both of Pharaoh’s problems. The die, my friends, has been cast. Now’s the time to skip for someone who can’t live with the hard facts. There’s nothing to stop anyone making a run for it.’

He and Balaam re-enter the palace without Jethro. He disappeared before we knew it, your majesty. Have him found and arrested.

They partake of drinks arrayed on a vast table..The butler, an Ishmaelite with the eyes of a cow, invites them to review a bewildering array of drinks, concoctions of everything from dandelion wine to a jug into which a horse’s neck has been stuck .The drinks are of every shade, from mauve to taupe. Of a subtle potency, they are served in every sort of container, from cut glass tumblers to gold and silver goblets.

Job lapses into a mindless acquiescence. Dusk came onto low-lying Luxor. A cacophony of croaking fills the head. From the dark river bullfrogs seem to croak the words: Covenant. Decree. Exile. Bondage. Suffering, suffering, suffering.

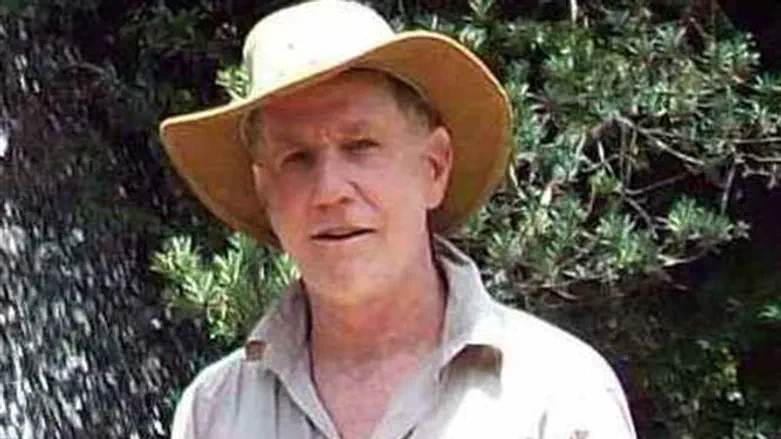

Steve Apfel is an economist and costing specialist, but most of all a prolific author of fiction and non-fiction.