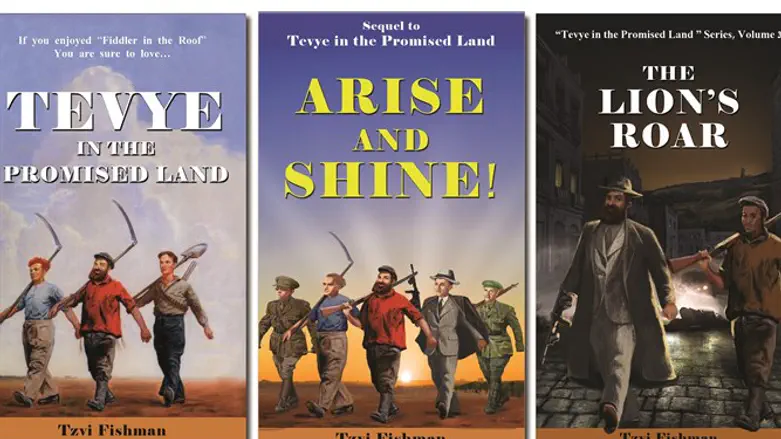

To honor the 140th birthday of Ze'ev Jabotinsky, here is a long and dramatic excerpt from Tzvi Fishman’s historical novel, "The Lion's Roar," from the trilogy, "Tevye in the Promised Land." The year is 1938, the Betar World Convention, Warsaw.

When Jabotinsky stood up to speak, a deafening applause filled the auditorium. Everyone rose to their feet. Tevye, Menachem Begin, Uri Zvi Greenberg, and the other Betar leaders on the stage, stood at attention, applauding. Truly, if there was a leader filled with the nobility and grandeur of Israel’s Biblical heroes of the past, it was Ze’ev Jabotinsky. When he held up his hand, everyone sat down in diligent obedience, like soldiers before their commander. An absolute hush fell over the packed hall. It was as if you could hear the beating of ten-thousand hearts. What, they wanted to know, was the message to be derived from the clank of the trap doors and the snap of the rope, still echoing from the corridors of Acco Prison?

In hanging Ben Yosef, the British wanted to teach the Jews of a lesson, but they turned him into a hero instead. The day after the execution, Betar hung notices all over the country:

SHLOMO BEN YOSEF

Hero of the Israelite Nation, the first Jewish martyr in Eretz Yisrael executed by the ruling authorities since the days of Rabbi Akiva – a pillar of fire to a Nation fighting for its freedom, was hanged by the British in Acco Prison.

His example inspired young Jews throughout the world to yearn for national liberation and freedom from foreign oppressors. In Eretz Yisrael, his tomb became an altar. Throughout the Diaspora, in cities with large Jewish communities, windows of the British Consulates were shattered. Jews attached a black ribbon to their coats in mourning for the heroic young martyr who had been executed while crying out, “Long live Jabotinsky!”

In the wake of his execution, a searing resentment flared throughout the Irgun membership in Palestine against the organization’s commander, Moshe Rosenberg. On his way to Poland, he received a telegram from Jabotinsky thanking him for his devoted work and relieving him of his position, to be replaced by David Raziel.

After Ben Yosef’s hanging, a profoundly disturbed Jabotinsky had written a letter in Yiddish to the martyr’s mother: “I do not merit that a noble soul like your son should die with my name on his lips. But as long as it is my lot to live, his name will live in my heart, and his disciples, more than mine, will be the trailblazers of the generation. It is not me who educated your son – it is he who taught me the meaning of Zionism.”

Jabotinsky gazed out at the expectant and already electrified audience through his thick, round eyeglass frames, as if through binoculars. He knew that everyone was anxiously waiting to hear his official reaction to the policy of restraint and appeasement which both the Arabs and British perceived as weakness and surrender. While opposed to acts of reprisal against innocent people, he understood that the “havlaga” do-nothing policy of the Jewish Agency had turned the Jews in Palestine into a community of impotent cowards. But first he wanted to say something about Ben Yosef.

“I know that everyone is angry over the dastardly hanging of Shlomo Ben Yosef,” he began. “I am angry too. We are angry at the crime committed against him and against the Jewish People, and we are angry at his murderers. Let not our anger blind us to the majesty of his heroism. Not his heroism in being ready to die for his country. Others have reached that great peak as well, and many others shall heroically do so in the future. The majesty of Ben Yosef lies in his perfect calmness in asking for a comb with which to properly coiffeur himself, that very same morning, as if he were beginning another ordinary day.

Martyrdom for Eretz Yisrael, he taught us, is not some fantastic, out-of-the-ordinary expression of courage. Sacrifice for our Homeland is as natural as combing one’s hair. This is the true meaning of Zionism.”

The giant audience sat in spellbound silence.

“It is a fact that Shlomo Ben Yosef and his comrades undertook their action without asking for prior permission of the Betar leadership,” he admitted, getting straight to the point.

“The three brave souls wanted to put an end to the disgrace whereby Jews are murdered with impunity, while Arabs remain free to commit their bloodthirsty deeds. Such an infamy must not be permitted!”

The crowd roared its approval. Raising his arm and magnifying his voice, he exclaimed, “If necessary, then post factum, I, as head of Betar, give you, Ben-Yosef and your two comrades, the order to go out onto the highway and do what you did!”

Once again, everyone in the hall rose to their feet in applause – everyone save the mysterious figure in the balcony, who stood by the railing, like a ship captain staring out at the horizon. What was going through his mind, Eldad wondered before turning his attention back to the stage. Rosh Betar motioned for the jubilant crowd to sit.

“There is a platitude that says it is immoral to punish the innocent in times of war,” he said. “What superficial and hypocritical nonsense. In war, any war, this theory purports that the general populace is innocent. There are even those who say: the enemy soldier who fights me, who has been recruited against his will, what crime has he committed against me that I should kill him? Or what crime have I committed against him that he should kill me? But when a war breaks out, we unanimously demand that a sea blockade be imposed against the enemy to starve the population, including innocent women and children. And if London and Paris are hit by an air raid, we demand air strikes against Stuttgart and Milan, even though they are filled with innocent victims. There is no war which is not conducted against the innocent. War is accursed, but if you do not wish to harm the innocent, you will die. And if you do not wish to die – then shoot and stop prattling! This lesson was taught to me by my teacher, Ben Yosef!”

Once again, Yisrael Eldad rose to his feet with the cheering audience. If this wasn’t a call to war – what was? Jabotinsky, the poet, acclaimed playwright and novelist, was like a skilled magician, revealing the mythic act hidden in the individual, heroic deed. Everyone in the hall knew the details of Ben Yosef’s last morning and hanging, but the master orator was to prove that no one recognized its true depth and the soaring heights that his martyrdom had lifted the Jewish People on their path to Redemption.

Up on the dais, Tevye applauded whole-heartedly along with the enthusiastic masses. Mortified to be seated on stage with Jabotinsky and other Betar luminaries, his refusals had been overcome by Rosh Betar’s emphatic insistence that he sit at his side. Caught up in the whirlwind of cheers and emotions accompanying the passionate speech, the milkman forgot about his embarrassment over being on the stage. Beside him, the young Menachem Begin, commander of Betar’s military youth groups in Poland, clapped half-heartedly, waiting to hear the rest of the speech. Though he revered Rosh Betar with all of his being, the “enfant terrible” of the 100,000-strong, Polish Betar recruits, had grown impatient sitting in youth groups criticizing the Jewish Agency’s submissive policy toward the British. His volcanic soul had grown restless with the Movement’s endless military drills, without any clear orders from Rosh Betar to retaliate against the continuous slaughter of Jews. Was “Jabo’s” de-facto approval of Ben Yosef’s deed meant as operative command for the future, or were the stirring phrases merely an ear-pleasing eulogy to hide their leader’s unwillingness to summon his troops into action?

“Everyone here is aware of the distressing situation in Palestine,” Jabotinsky continued. “Since many of you undoubtedly have reservations about our policies, allow me to present a brief history, without going into detail, as a basis for clearheaded discussion. When the Irgun Zvai Leumi broke off from the Haganah, I had no official position of authority. Soon afterward, it was decided that my suggestions were to be followed concerning overall policy, and that I would have the authority to appoint the organization’s commander in Palestine. However, since the British have barred me from returning to our country, all local decisions concerning activities in Eretz Yisrael are decided upon by the commanders on the scene.

Meeting with the Irgun leadership in Egypt, we discussed what action should be taken in regards to the ongoing policy of havlaga. While understanding the desire for reprisal, I questioned the moral justification for such actions, since innocents not connected with the killing of Jews could be harmed in such forays. I questioned what public good would come of shooting an Arab peasant in the back on his way to sell vegetables in the market. After an unauthorized attempt to assassinate a certain Arab leader, now hiding in Lebanon, was attempted without success, the possibility was brought to my attention of eliminating him, for a certain sum of money, in light of the fact that he continues to direct terrorist attacks against the Jews in Eretz Yisrael.”

Jabotinsky didn’t turn toward Tevye when he said it, and Tevye’s expression didn’t change.

“I vetoed the proposal. ‘Would we like to see our enemies assassinating people like Weizmann and Ben Gurion?’ I asked. In addition, how could I authorize people to undertake such a dangerous mission when I sit comfortably in London and Paris?”

Yisrael Eldad, and all of the people surrounding him, listened in rapt attention. While everyone read newspaper articles about events in Palestine, the information was reported in a superficial manner, nothing like hearing an insider’s in-depth explanation.

“When more and more innocent Jews were butchered in the unabated Arab uprising, and the demand to retaliate increased, I struggled day and night with the need to make a decision, tormented by the dilemma of ordering troops into life-risking actions when I myself couldn’t share the dangers. On five different occasions, I wrote the awaited telegram with the code giving my approval, and five times I called the messenger back before he reached the post office. When Jews acted on their own, I was glad, but I still refrained from breaking the standing policy of restraint fostered by the Jewish Agency and the Haganah, hoping that if the British didn’t crack down on the uprising, I could reach an agreement with the Haganah to combine forces and thus make our response much more unified and effective. Badgered by our comrade, Mr. Begin, and by local commanders in Palestine whose soldiers were foaming on the leash of havlaga, I told them, ‘Men fregt nit dem Taten - a son shouldn’t always ask his father’s permission.’”

His remark drew a response of laughter, temporarily breaking the heaviness of his words. Menachem Begin smiled broadly, showing an uneven front row of teeth.

“When bombs were planted in Arab markets and bus stations, the British demanded that all retaliations cease. They displayed their displeasure by rounding up dozens of known Revisionists and Betar activists. My son, Eri, one of the randomly arrested, is now being held under military detention in Acco Prison, where I had the dubious honor of living for many months, along with many dear comrades in arms. My son is incarcerated for being a Revisionist, and I am proud of him for that. The Jewish Agency called the reprisal attacks ‘acts of terrorist aggression undermining the moral standing of the Jews of Palestine.’ Eliahu Golomb, head of the Haganah, hurried to meet with me in London. While our politics differ, he is a soldier’s soldier, with the interests of the people of Zion at heart. First, I told him, before any agreement can be reached, both in regard to a cease fire, and in regard to a pact between the Irgun and the Haganah, the Jewish Agency’s reprehensible practice of providing the British Police with the names of Revisionists and Betar activists must come to an immediate end.”

“No deals with informers!” came a loud cry from the

balcony. Other Betar cadets surrounding the mysterious figure shouted catcalls of their own.

“Jewish traitors!”

“Remember the Stavsky trial!”

“It’s time for action, not speeches!”

Uri Zvi Greenberg rose to his feet. “Like the brothers of Yosef, the disciples of Lenin and Marx will throw us into the dungeons of the British!” he declared.

Tevye wanted to add a ripe curse of his own, but who was he to voice an opinion before such a distinguished gathering?

Yisrael Eldad could not remain silent. “Uri Zvi Greenberg is right!” he shouted. “Making an agreement with the Jewish Agency is like throwing Betar into a pit with spiders and scorpions!”

Jabotinsky held up a silencing hand. “I told Golomb that I couldn’t speak for the tens of thousands of frustrated Jews in Palestine, nor influence the decisions of local Irgun leaders who had grown tired of restraint and defense. For good or for bad, I explained that as the head of Betar, and the World Revisionist Movement, as well as Director of the New Zionist Organization, which are all legal bodies, in order to protect their official standing, I cannot associate myself with underground movements.

Nonetheless, I told him, the urge of Jews to strike back at their murderers will not be crushed by arrests and imprisonment.”

The crowd applauded, returning, for the moment, to Jabotinsky’s corner. Israel Eldad was not swayed by the emotional appeal. He knew that after the spectacular “Black Friday” reprisals in Jerusalem, of which he had not been consulted, Jabotinsky refused to sanction further underground actions. While Jabotinsky presented a militant image in public, when it came to street bombings, he was inwardly riddled with moral doubts. Eldad sensed that the statesman in Jabotinsky continued to believe that the success of Zionism would come about through international negotiation and endeavor, and that the Irgun was to subordinate its local activism to the needs of the overall political scheme.

“Without a doubt, the message of ‘Black Friday’ brought a temporary end to the Arab terror in Jerusalem,” Jabotinsky admitted. “After the fiasco of the Peel Commission, with the renewal of the Arab uprising, and the deed of Shlomo Ben Yosef and his friends, Golomb requested a meeting again in London, fearing that private Jewish militias would distance the British from the Zionist cause. He told me that he didn’t want civil war to break out in Palestine, implying that the Haganah would be forced to wage war against militant Jewish forces in the Yishuv if they didn’t agree to come under the Haganah’s leadership. Golomb is a serious individual, and his threats need to be taken seriously. The Left is accustomed, in the tradition of the Bolsheviks, to deal violently with ideological opponents, as we have learned from the ignominious blood libel they waged surrounding Aronov’s murder. Already they have handed over dozens of our followers to the British. But, to Golomb’s credit, he is a wise and reasonable man, very aware of our strengths, as well as our joint national weakness. Because of this, we were able to reach an agreement.”

The announcement was met with mix boos and cheers. Jabotinsky continued.

“It was decided that a commission composed of four members, with equal representation between the Haganah and the Irgun, would decide upon all military actions. Each organization would remain autonomous in its ideology, structure, and command. Furthermore, in every case where the Haganah’s forces were awarded recognition by the Mandate Authorities as legal defense units, the Irgun would have a share. Unfortunately, as I expected, the agreement was sabotaged by Ben Gurion, who spends much of his time in London, battling Weizmann for control of the World Zionist Organization. Ben Gurion’s correspondence with Golomb was intercepted by Irgun Intelligence. In his telegram, he wrote that Golomb’s efforts to form a merger were a grave breach of discipline. ‘If the agreement is not signed, don’t sign it,’ Ben Gurion ordered. ‘If it is signed, then annul the signature!’ In a subsequent wire, he wrote: ‘Jabotinsky plans to blackmail the Zionist Organization, which we lead, to accept his breakaway group as an equal partner, by carrying out reprisal attacks in Palestine which we consider to be dangerous to our cause.’ Thus, out of his paranoid fear of losing control of the Zionist Executive, Ben Gurion succeeded in preventing a union of forces which surely would have saved Jewish lives and strengthened the Yishuv. ”

“To hell with Ben Gurion!” someone shouted.

“Life isn’t so simple, my friend!” Jabotinsky shouted back. “The Cossacks in charge of Mapai are capable of throwing all of us into prison and throwing away the key. Once again their informants are collaborating with the British Police. You can be sure their double-agents are sitting in this auditorium today. Like the Bolsheviks they secretly admire, achieving domination and control justifies all means. To achieve their goals, they are capable of anything, even surrendering vast chunks of our Jewish Homeland to imposters who claim that our eternal inheritance belongs to them!”

“Traitors! Traitors! Bogdim!” voices called out.

“If they open fire on us, we will shoot back at them!” one of Eldad’s neighbors shouted, waving a Betar flag in the air.

Menachem Began jumped to his feet. “No!” he shouted. “Their way is not the way of Betar. There will be no civil war. Let us all march off to prison before we lift a hand against a brother!”

His outburst brought cheers from the audience. Jabotinsky waited until the applause for Begin ended. Nodding toward his young disciple, he turned back to face the energized crowd in the auditorium.

“Jews will no longer act like frightened mice!” he exclaimed, raising a fist with emotion.

“Today, a Jew in Eretz Yisrael cannot drive out of his moshav in the Galilee without risking his life.

Attacks along the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv highway are just as frequent. Jews have to travel in convoys. After being shot at several times, if he hasn’t been wounded or killed, a Jew thinks twice about traveling the roads of his country. Outside the confines of his house or community, his life is in danger. Often his wife pleads with him not to travel. ‘Why be a hero?’ she asks. Thus, in his very own Homeland, the Jew becomes like a trembling mouse in a cage, while the Arabs travels freely in absolute safety, like sultans in their palaces, even in Tel Aviv.”

Eldad felt his blood boil. What was the matter with the Jews? Jabotinsky raised his voice.

“Why should the highway robbers refrain from killing when we turn the other cheek? I call them highway robbers, but they call themselves ‘freedom fighters.’ They are heralded as saviors by their people.

Flowers are thrown at them in honor. Songs are written about them. Arab terrorists see themselves as national heroes.

“Two years ago, the Jews were the majority in the Old City of Jerusalem. Now most of them have fled in fear. Arabs have taken over their homes. The British assist the Arab cause by evacuating the Jews who remain. When we complain to the authorities, they answer, ‘What do you want from us? The Jews are afraid to live there. We are protecting them by helping them move to another part of the city.’”

“This disgraceful situation must cease. Havlaga must be erased!” Jabotinsky finally cried out.

Cheering, aisle by aisle, everyone rose in approval. Jabotinsky paused once again until they were seated.

“The world must not be allowed to believe that Jews will let themselves be murdered without responding measure for measure!”

Eldad, who was standing far back from the stage, could see the fire in Jabotinsky’s eyes.

“Today, a Jew who breaks the havlaga is considered a criminal in the eyes of the British, and in the eyes of the Jewish sycophants who control the Yishuv. Let some Englishman ask me who broke the havlaga in the defense and honor of his People – I will answer that I do not know. We are not obligated to supply names and addresses to the British, nor to Jews who incriminate their brothers.

“The havlaga in practice today in Eretz Yisrael must be broken. If we allow it to continue, the whole world will say that the Arabs are the landlords and that we are the encroachers, when exactly the opposite is true. Where is the morality in the situation where one side can murder and steal, and the other side is forbidden to react? If the British enact laws prohibiting Jews from safeguarding their lives, then these laws are immoral at their very foundation. I declare to you that the Supreme Conscience, the Divine Justice, demands that the havlaga be broken, and that anyone who does so is free of guilt. And if, wherever on this planet, there is a Jew who maintains that those who break the havlaga are guilty, than he is a cursed criminal, and his lowly betrayal of his People will be a lasting and unpardonable blemish in the history of the Jews.”

The Betarim rose to their feet in a roar of consent.

“It turns out that we are our own greatest enemy in allowing this situation to persist. The Zionist establishment insists that, in the name of morality, Jews not employ the same violent paths of the Arabs. Where is the morality in this?! By letting ourselves be slaughtered, even the friends we have amongst the nations will say that if we are not willing to fight for our Homeland, it must not be ours.

“The truth is, the Jews in Eretz Yisrael are happy when the havlaga is broken. Unlike the leaders of the Yishuv, they still have common sense. Every day, they gaze at newspaper headlines, hoping to see news that Jews struck back against their oppressors. Believe me, even advocates of the havlaga don’t believe in its effectiveness and justness, and only expound restraint and concession as a diplomatic means of maintaining their standing with the British. So if someone declares to you that he is a believer in the havlaga, tell him to go and tell his fairytales to his grandmother.”

The jocular expression brought laughter and cheers from his listeners. Returning to Ben Yosef, he said:

“I have often spoken about ‘Hadar.’ All of the distinguishing features of nobility, the nobility of the soul, valor, moral refinement, knightliness, the willingness for self-sacrifice for the Nation, all of these were contained in the heart of a young Jewish man from Rosh Pina who has become a symbol for all of us, a youth whose noblesse of spirit has captured the admiration of the world, and behold, he was a simple Betar cadet who G-d chose to elevate in the ranks. I am not worthy of speaking about him, but I can tell you that the British were stunned by the example he set, and they have begun to understand the meaning of ‘Hadar.’ Shlomo Ben Yosef remained true to his oath to Betar and to our Nation. He wrote on the wall of his death cell: ‘To die or to conquer the hill.’

“A Jewish guard who was on duty that morning in Acco Prison related that Ben Yosef guarded his nobility to the very last moment when the trapped doors opened beneath him and he descended into the abyss below with a smile on his lips. The policeman said that what separated Shlomo Ben Yosef from the doomed men whom he had accompanied to the gallows was the young man’s utter peace of mind in the face of his imminent death. Other prisoners facing execution succumbed to despair, not caring how they looked, or about eating breakfast in the morning. But Ben Yosef calmly asked to wash and brush his teeth. Proudly, he dressed in his Betar uniform and left his cell singing, filled with one powerful faith in his heart and no other, graced with ‘Hadar,’ and an exalted splendor, winning a great victory for all of us from the hands of his executioners.”

Utter silence filled the large hall. Yisrael Eldad, who himself had a gift for words, sat in awe of Rosh Betar who was clearly infused with Divine Inspiration.

“A short time later, I visited Ben Shlomo’s mother in Poland. She sobbed in my arms. I too wanted to weep, but following the example of her son, I did my best to strengthen her spirits, just as he has strengthened ours. While I harbor a deep aversion in asking favors from the British overseers of Palestine, I wrote to Malcolm MacDonald, Secretary of State for the Colonies, with the request to intercede with the Palestine Authority in granting immigration certificates to Rachel Tabacznik, Shlomo’s mother, along with the members of her family. I promised that we would provide her with a small house in Rosh Pina where her son is buried, and that we would provide for her financial well-being if necessary.

‘Whatever the attitude of the British Government toward her son’s actions,’ I wrote, ‘I trust that a nation known for its moral refinement will respect the pain of a mourning mother and sympathize with her wish to end her days near the place where he son was laid to rest.’ I never received a response from my letter.”

“Gentlemen,” Jabotinsky concluded. “The goal before us is clear, and we recognize the foes and forces which stand in our way. I wish that G-d will grant you the power to fulfill your oath – your oath of allegiance to the Redemption of Am Yisrael.”

A long round of applause met the conclusion of the speech, respectful, even awe-filled, but lacking the crowd’s initial enthusiasm over Jabotinsky’s opening words. Eldad himself was confused by the ambiguous messages. What was to be the official Revisionist policy – continued restraint, occasional retaliation, or outright revolt?

“Enough speeches!” a young voice called out from the balcony. “An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth! Enough Jewish blood has been spilled!”

The spontaneous call was followed by shouts of agreement. The main chorus of dissent came from the upper gallery. The mysterious figure had vanished. Later, Eldad discovered that he had organized the outbreaks against Rosh Betar.

“Blind revenge is neither practical nor politically expedient at the present time,” the embattled leader called back.

“The hell with political expedience!” a voice in the crowd answered. “The blood of our brothers cries out from the earth!”

“It’s time for armed resistance against the British!” another young, angry voice shouted. Jabotinsky shouted back at the heckler.

“It is utter nonsense to think that conditions exist in Palestine for a Garibaldi-like Jewish war of liberation against the British. As long as we lack the means to establish and sustain an independent Jewish State, it is incumbent upon Zionism to pursue policies that will enable it to appeal to the world’s conscience.”

Suddenly, Yisrael Eldad heard himself calling out, “When it comes to the Jews, the world has no conscience!”

The crowd stilled, waiting for “Jabo” to answer. Eldad felt his legs trembling.

“To say that conscience no longer exists – that is despair!” the besieged commander retorted. “Conscience rules the world. I respect it. It is forbidden to mock it.”

Uri Zvi Greenberg rose, shook Jabotinsky’s hand, and quietly walked off the stage. Could it be that he didn’t want to be present to witness more arrows fired at the man who had revived Jewish pride and a rekindled a fighting spirit more than anyone else in the century? Or maybe he didn’t want to speak out against Jabotinsky in public. Yisrael Eldad wanted to greet Uri Zvi Greenberg as the poet left the hall, but he remained in his seat, sensing that fireworks were about to explode.