In recent weeks, both Avigdor Lieberman of Yisrael Beytenu and Naftali Bennett of Jewish Home have proposed legislation known as the "Norwegian Law" to change the way Israeli governments operate. While, under current Israeli law, a member of Knesset appointed to be a minister would serves simultaneously as a minister in the executive branch and an MK in the legislative, the Norwegian Law removes the new ministers from the legislature and allows lower-ranking members of their respective parties to take their seats in the Knesset.

While relinquishing one's status as MK upon appointment to the government is currently an option, it would become mandatory under the Norwegian Law, and not a matter of choice.

"Adoption of the Norwegian model will help in improving the work of the Knesset, the stability of the government and the Knesset's image," said Jewish Home #3 Ayelet Shaked last week.

The issue is one that parliamentary systems like Israel's face, and which spoils-system governments like the United States do not encounter. When forming a cabinet in Israel, the top members of each coalition party receive ministry titles. The head of the largest party becomes Prime Minister, while larger partners tend are rewarded with top-status ministries like Defense or Foreign Affairs, and junior partners lesser prestigious ministries like Transportation or Religious Affairs.

Why now though?

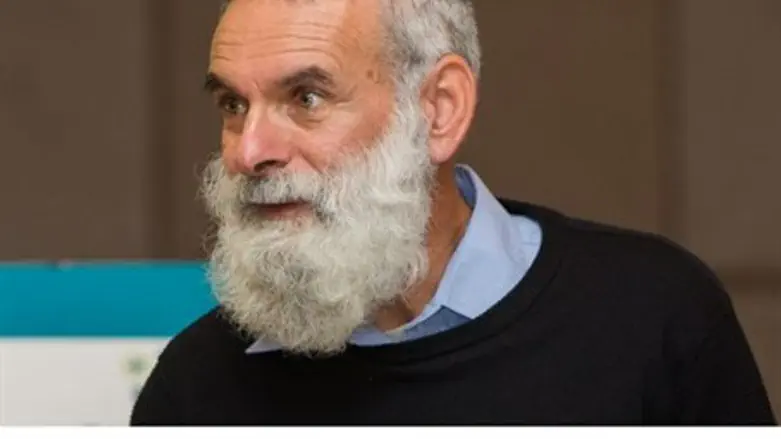

"Basically, it is to give more people on an electoral list positions because that will get additional positions in the Knesset," says Professor Gideon Rahat of the Israel Democracy Institute. "This might also be good for the health of the system. This would add more active members to the Knesset. Currently, each minister is also an MK, so they (often) can't do their jobs as MKs when serving as ministers.

"You would have more active parliamentarians, which is also important considering the relatively small size of the Knesset."

The bill would have huge implications for junior politicians who might miss out because senior members of parties would still hold onto Knesset seats otherwise.

For example, if Jewish Home's top four members were to receive ministries or become Deputy Ministers, that would allow spots 9, 10, 11 and 12 to take their place as MKs. If just three Likud members became ministers (and that number is likely to be much higher in the next government), that would mean previously unlikely MK #33 Rabbi Yehuda Glick would enter the Knesset and have the chance to speak about less mainstream issues like prayer rights on the Temple Mount.

When asked if the Israeli system of handing ministries to political figures rather than professionals was a proper one, Rahat said that the professional staffs of the ministries, which are generally not politically appointed, would continue to steer their everyday function.

"I don't think this is a problem or a must (to have professional ministers). There need to be politicians who represent a position or an ideology," he added, noting that this is how parliaments work around the world.

"They have this in several countries and I think the parliaments there are quite known to be no worse than others and sometimes better than other parliaments."

There is the issue of budget, though. Currently, MKs receive a monthly salary just under 40,000 NIS a month. The addition of new MKs would definitely increase the amount being spent on salaries and staff for politicians, but in Rahat's mind this is a price worth paying for the efficiency and productivity the Norwegian Law would add to the Knesset.

"It could be one thing used to argue against it. In my opinion, the price is fine. In a democracy, you have to pay your representatives and at this stage it's a worthwhile payment."

Rahat sees the possibility that harder-working MKs could strengthen the amount of checks and balances between the legislative and executive branches. With MKs completely dedicated to their roles in parliament, they will be more inquisitive regarding ministry business and continue to urge implementation of policy: "On the one hand, you're bringing them in to be active members of the Knesset (for party interests) and on the other hand is an interest in government stability. So in a sense, you put them in under two different pressures.”

This can also serve another purpose: preventing the addition of unnecessary ministers in the next government. While people like MK Miri Regev of Likud have advocated in recent days to undo the last government’s reform of restricting the cabinet to 18 ministers, Rahat sees this as a compromise that will give parties the share of government they want while protecting efficient government.