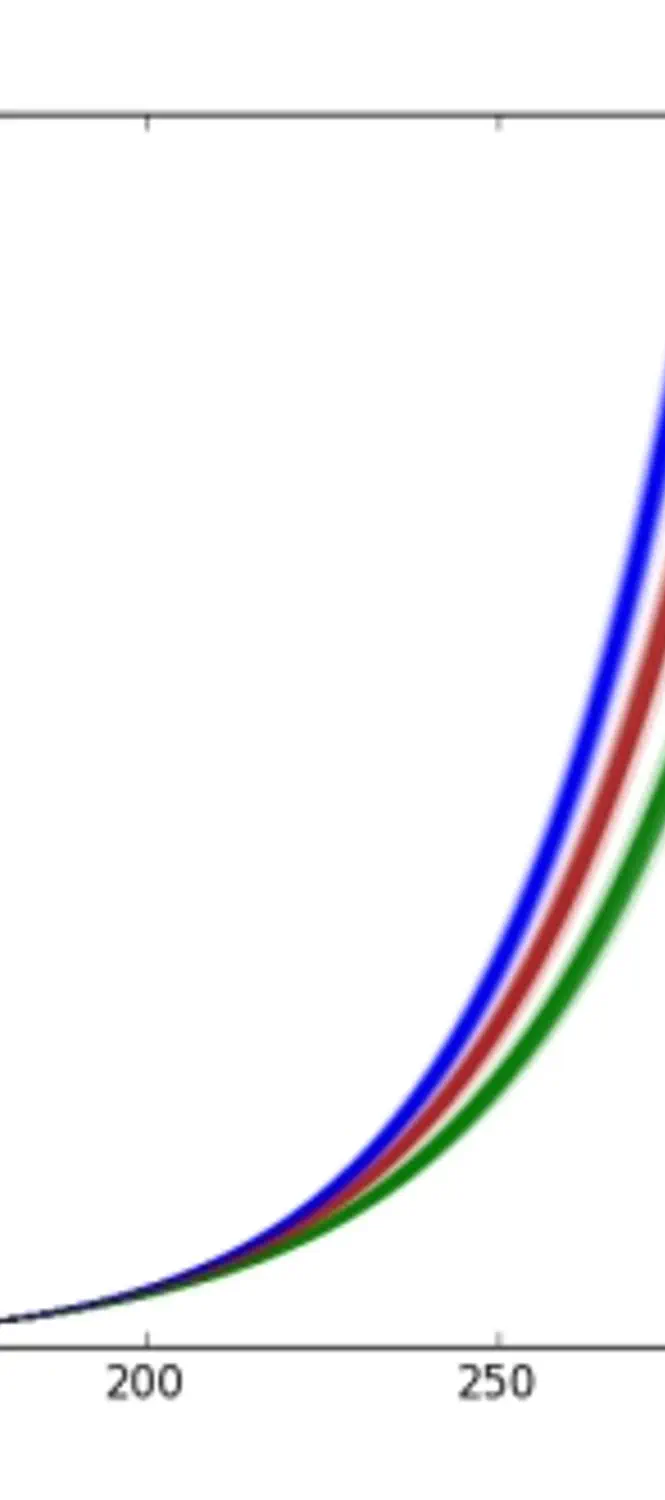

A recently published statistical analysis funded by US Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) predicts that there will be approximately 230,000 Ebola infected people in the West African countries of Liberia and Sierra Leone by December 31, 2014. This would mean approximately an additional 220,000 cases by the end of 2014, above what currently exists in the Ebola affected areas of West Africa.

In short, this means over 100,000 new cases per month for November 2014 and December 2014. The study concludes that improved “interventions are not sufficient to halt the progress of the [Ebola] epidemic.”

Since Liberia has a total population of only approximately four million (4,000,000 pop.) people, this would mean that close to 5% of Liberia’s total population will become Ebola-infected by Dec. 31.

The study found a relatively small range of “several thousand cases between the most optimistic and most pessimistic scenarios.” However, it added, “the number of cumulative cases is forecast to continue rising extremely rapidly, with the bulk of the epidemic yet to come. This suggests an extremely poor outlook for the course of the epidemic without intensive interventions.”

“Person-to-person” transmission made up almost the majority of the causes for transmission cases with “funerals” and “hospital transmissions” making a much smaller impact.

The principal functional differences between the “best case” and “worst case” case lay in the studies assumptions of improved “contact tracing.”

“Contact tracing” means an analysis by the health care worker of the people who were likely infected by the acutely-infected Ebola patient. The study reported that there was a “baseline scenario of 51% in Liberia and 58% in Sierra Leone.” The study analyzed projections based on 80%, 90%, and 100% “contact tracing.” In Liberia, 100% “contact tracing” with early hospitalization still projected 80,000 Ebola infected compared with 140,000 Ebola-infected for 80% “contact tracing.”

The study explains that: “In principle many of the measures to contain the spread of Ebola, such as intensive tracing of anyone in contact with an infected individual and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for healthcare personnel treating infected cases, are straightforward. However, implementing those interventions in a resource poor setting in the midst of an ongoing epidemic is far from simple, and subject to a great deal of uncertainty.”

The study fails to explain how Liberian health workers inundated with exponentially accumulating Ebola cases could increase their contact tracing from 51% to 80%.

The study dramatically concludes that:

“The ongoing Ebola epidemic in West Africa demands international action... many of the interventions currently being implemented... will have a positive impact on reducing the burden of the epidemic. However, these results also suggest that the epidemic has progressed beyond the point wherein it will be readily and swiftly addressed by conventional public health strategies. The halting of this outbreak will require patient, ongoing efforts in the affected areas and the swift control of any further outbreaks in neighboring countries.”