It's no secret that Israeli society has its fair share of fissures, with competing ideological and religious camps whose positions sometimes appear hopelessly irreconcilable. That is of course what made the national unity exhibited during the past several months so remarkable; the kidnapping and murder of the three teens in June and the recent war with Gaza appear to have jolted us awake - if momentarily - to the fact that, whether we like it or not, we really are all in this together.

Nonetheless, it is clear that at least some of the simmering points of contention will sooner or later reemerge - whether over the political process with the Palestinian Authority (and now Hamas), or the relationship between religion and state.

And yet, it is easy to forget that even the most ferocious ideological clashes of today are a mere shadow of the sometimes murderous rivalry that once threatened to split the Jewish people in two.

How My Grandmother Prevented a Civil War is a window into just such a time, a mere two or three generations ago, when the prospect of a deadly internecine war between Jews in the land of Israel was frighteningly real.

The plot itself could not be filled with more intrigue: A young Irgun commander named Yedidyah Segal is kidnapped by the left-wing Haganah - soon after, his lifeless body is discovered showing signs of torture. The Haganah denies responsibility, claiming their prisoner escaped and was murdered by Arabs; the Irgun, like many others in the country at the time, do not believe them. Negotiations between the sides for a united front on the eve of the War of Independence falter, and civil war threatens to snuff out the nation's hope of freedom before the Arab armies even fire their first shot. Only the courage of the victim's remarkable parents - Yosef and Malka Segal - could prevent the unthinkable from occurring.

The book itself is a determined attempt by the author Hagai Segal - Yosef's great-grandson, veteran Israeli journalist and Editor-in-Chief of the Makor Rishon newspaper - to find out what really happened on that fateful day and answer the question: who killed Yedidyah Segal? In doing so, he provides a fascinating tail of bravery, strength of character and, above all, hope in the inner strength of the Jewish people to overcome seemingly insurmountable crises - sometimes through the decision of just one or two brave people.

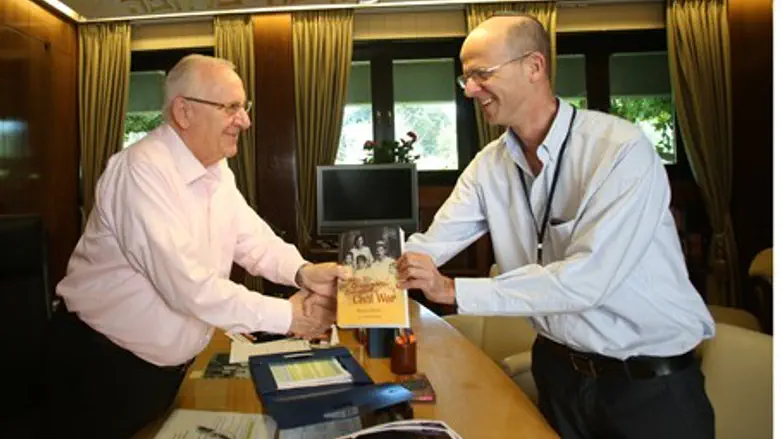

The Hebrew edition was critically acclaimed, including by Israel's President Reuven Rivlin, who hailed it as "an incredible and extremely important" work.

Below is an edited transcript of my interview with Hagai, and the first review of his work since it was translated into English:

The story itself takes place against a historical backdrop that isn't familiar to most people today. Even with all the present-day political controversies the notion of Jews kidnapping, torturing and potentially murdering their rivals is unthinkable.

Before we delve into the book itself, what in your opinion lay behind the fierce hatred between the Haganah and Irgun at the time, and how has that hatred contributed to the political discourse today?

I think that first of all in those days people were simply more ideological, and so therefore the rivalry was so much fiercer.

Essentially, what they were fighting over was how best to establish the State of Israel - with force, through settling the land, through aliyah... And of course, in the background as well was the controversy over who would rule the state after it received independence: the Right or the Left, Begin or Ben Gurion.

So of course there was great tension.

Today as well there is tension, often along the same ideological fault lines, but I think that back then it was much easier for it to go all the way to violence. The conflict was so much greater.

What's interesting is that the side which so vehemently opposed the use of violence in pursuit of independence (the Haganah), was also the most violent towards its political rivals...

That's a good point. It's always been like that. Even today on the Left you have people who are prepared to negotiate with the Arabs but aren't willing to make peace with "the settlers".

But it's not an exact parallel.

Today, despite the fact that there is also a serious internal conflict - which sometimes features very harsh language - back then it was simply far, far worse... And more violent - which is how it got to actual bloodshed.

I think that, all in all, (Irgun leader) Menachem Begin's decision to adopt the position of avoiding a civil war at all costs - and my grandparents felt the same way - that approach was the correct one.

It would not have helped in any event to respond with violence.

Yes, there are those on the Right who lament the fact that "we were silent", particularly regarding the Altalena [an Irgun arms ship which was sunk some time after the Segal affair by the Haganah, killing 16 Irgun fighters and destroying most of its badly-needed cargo destined for the nascent Israeli army - ed.], but I think that it would not have helped anyone - not the Revisionists [Irgun], and not the Mapainiks [Mapai was the left-wing Zionist party of Ben Gurion which dominated the Haganah - ed.]

No one wins in a civil war.

That was precisely the argument which resurfaced again a decade ago with the Disengagement from Gaza...

Yes, and even then then it would not have helped to resort to bloodshed - although there are also those on the Right who say we should have used more force.

I have to say that I'm somewhat less sure about this case - the question of whether more force should have been used to resist the expulsion from Gush Katif - but ultimately I would say that even if force had been used it would not have saved Gush Katif, it would have just led to bloodshed.

Begin always said that we lost the Second Temple because of a civil war. It can't be that we return here after two thousand years and immediately launch another civil war!

From a historical perspective, isn't it strange that a revolutionary movement such as the Irgun, which had a very clear vision for how it wanted the state to look, did not seek to seize power? It's perhaps unique in the history of revolutionary movements - why?

I think you could do many academic studies on just that question, and I don't really have a detailed answer to that. But it is clear to me that Begin wanted first to establish the state, and then we can decide who's in charge. The Mapainiks, like Ben Gurion, approached it in the opposite way...

Back to the book itself: You chose to begin with a quote from Devarim (Deuteronomy 21, which outlines the laws of egla arufa - the responsibility a community must take if a dead body is found nearby amid unclear circumstances). That seems to imply that you approached this as more than just a personal investigation into a family tragedy, but rather as a project with wider - perhaps national - implications.

That's true. In the War of Independence for example 6,000 Israelis fell - that's a lot of people, more than twice the number who fell in the Yom Kippur War (and approximately 1% of the entire population of the State of Israel at the time.)

But the majority fell fighting the enemy Arab forces. In this case, the victim died at the hands of Jews, and that makes it so much more painful.

This is not just a family story - it's something much greater. I really think that the restraint of Yedidyah's family helped prevent a civil war at a time when we were already under attack. The restraint my family exhibited may well have saved the State of Israel. So it's not just a personal story.

So why bring this out now? Some had suggested you were opening old wounds...

Well first of all, history is important - you need to know your history.

Secondly, I didn't write this to reopen the whole episode, but more in order to tell the story of my grandparents, their incredible journey from as pioneers in Eretz Israel, and how they overcame such a terrible event.

And it's not just history. From time to time these kinds of episodes come up - as you mentioned, it came up during the Disengagement - and in 20 years' time for all we know the story's lessons could still be as relevant as ever, so it's important to deal with the question: how do we prevent a civil war?

In many ways the hero of the story is Yosef Segal, a man who somehow always saw beyond the different political camps and ideological splits and focused on the bigger picture. He supported the Irgun and Lehi undergrounds yet still admired their arch nemesis Ben Gurion - and he saw no contradiction in this. Where did he draw such an outlook from?

That is precisely the message of the story. He looked at everything from a perspective beyond his own personal situation - he had a much wider outlook. He believed that in the 20th Century he was witnessing something truly momentous happen to the Jewish people, after so long in exile. So even after such an enormous personal tragedy, he couldn't allow it to derail the process.

His outlook was a bit like that of Rav Kook [leading religious-Zionist thinker Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Hakohen Kook - ed.]

I don't think he ever read Rav Kook's works - he knew him personally, but he wasn't a student of his - but his outlook was the same He was above all the arguments and he loved everyone equally; religious, secular, left-wing, right-wing...

Even after the murder...?

For sure. It was almost as if just went back to normal. He never spoke about it. It's like today, when families whose sons fell in Gaza comfort themselves with the fact that they died for the sake of the homeland...

But as you yourself said, this was at the hands of his fellow Jews.

True, but he (Yedidyah) still died for the sake of the homeland.

He (Yosef) also pushed it to the back of his mind psychologically, because he didn't want to think about it. He didn't even sit shiva [the customary seven-day period of mourning - ed.] in the usual way. I only realized that when I wrote the book. He didn't sit with the rest of the family - that's what my relatives told me - it's as if he just wanted to move on.

That's not because he wasn't sufficiently sad over the death of his son, but because he understood that there was a greater purpose.

What was your family's reaction to the book?

The truth is that most of the people mentioned in the book are no longer alive. Only two of my aunts remain, who are both in their eighties, and they were young girls at the time. They both read it and their feedback was very positive.

What was the most difficult part of your investigation?

That I never really managed to get a final answer to what happened to Yedidyah.

I made a lot of progress, but ultimately I didn't succeed. I suppose I had hoped that after 60 years someone who knew might say "You know what, it's been long enough - here's what happened", but they didn't.

I think there is no doubt that he was killed by the Haganah. But the precise circumstances, the how and why, I couldn't get to the bottom of.

If there is a message you would like both political camps in Israel to take from this story, what would it be?

To be careful and know where hatred can lead to, and to have faith in the special qualities of the Jewish people. It is a truly special people. And also, to be optimistic even when difficult things happen.

Ultimately it's an optimistic book. It recounts some truly terrible events but somehow from all of that it leaves you with a lot of hope for the future of the Jewish people.